Infrastructure in

America

Climate Resilience on Detroit’s East Side

On a hot, sticky morning on Manistique Street, in Detroit’s Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood, Tammi Black and a group of friends and neighbors who call themselves the “Women of Empowerment” are gathered beneath a shade umbrella in a vacant-lot-turned-community-garden adjacent to Black’s home, a cooler of ice water at the ready. Half a mile to the south, water from the Detroit River is pouring into the neighborhood, over the edges of the canals that lace this historic part of the city’s east side. The river water is flooding streets, overwhelming the combined sewer system, and leaking into basements. Sandbags provided by the city are piled in stacks across driveways and sidewalks in a mostly vain attempt to stop the deluge.

The Women of Empowerment gather at Black’s home once a month to share stories and scheme about ways they can be a force for resilience in a city that still, despite a downtown “comeback,” experiences high levels of poverty, low educational attainment, and blight. Wealth and access to resources in the city remain divided along lines of race and class. All of this means that climate change and its attendant heat waves and flooding affect certain neighborhoods—like Jefferson Chalmers—more heavily than others.

The "Women of Empowerment" meet at Tammi Black's home in Jefferson Chalmers (Nina Ignaczak)

The "Women of Empowerment" meet at Tammi Black's home in Jefferson Chalmers (Nina Ignaczak)

Manistique sits just two blocks from Alter Road and Fox Creek, which has for a generation served as a dividing line, a moat between worlds. East of the divide is Grosse Pointe Park—eighty-six percent white, with an average home value of $435,394. More than sixty-five percent of homes were built before 1939, and are equipped with functional air conditioning and heating systems. Travel east of the divide, on one of the few roads not blockaded by barriers constructed since the 1960s rebellions, and you enter Jefferson Chalmers—eighty-six percent Black, with a median income of $30,700 and an average home value of $47,307. Homes here are older, and often lack access to modern temperature controls.

When heavy rains overwhelmed sewer systems in the area in 2011, 2014, and 2016, and 2018, residents of Jefferson Chalmers and Grosse Pointe Park found themselves dealing with basement flooding and property damage. But they had vastly different resources available for dealing with it. Many Grosse Pointe Park residents had private insurance to cover their losses, while few Jefferson Chalmers residents did. “It’s sad to wake up at three o’clock in the morning, and you go to your basement door and you see your freezer floating by,” says Betty Mills, one of the Women of Empowerment.

Mark Cornillie is a resident of Grosse Pointe Park who experienced the basement flooding. He remembers in 2014, “there was just stuff piled up on the street from people’s basements all the way up and down the block.” A group of Grosse Pointe Park residents eventually filed a lawsuit against the City of Grosse Pointe Park and won a settlement in 2019. “It nowhere near covered the losses,” says Cornillie. “We had some people who had losses totaling over a hundred thousand dollars. But only ten of the people affected joined in the lawsuit, because most of them had private insurance that covered their losses.”

Black remembers the flooding bringing neighbors in Jefferson Chalmers together. “A lot of our senior citizens didn’t have anyone to help them clean up. They were living with the mold, and breathing it in. The neighbors banded together to help each other.” They filed a class action suit against the City of Detroit, and eventually received a settlement.

Donna Givens is the CEO for the Eastside Community Network, a thirty-year-old community development nonprofit focused on Detroit’s east side. She is concerned that, because of the high water levels and resultant flooding, the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood may become a designated high-risk FEMA flood zone, which would require mortgage borrowers to purchase flood insurance under federal law.

Right now, each property owner is responsible for maintaining their own sea wall. Some have one, and some don’t. “When you look at why people in Jefferson Chalmers may have to have flood insurance, and people in Grosse Pointe Park don’t, it has everything to do with the fact that Grosse Pointe invested in a sea wall,” says Givens. But even that sea wall, which was built back in the 1920s, is now deteriorating and needs to be replaced.

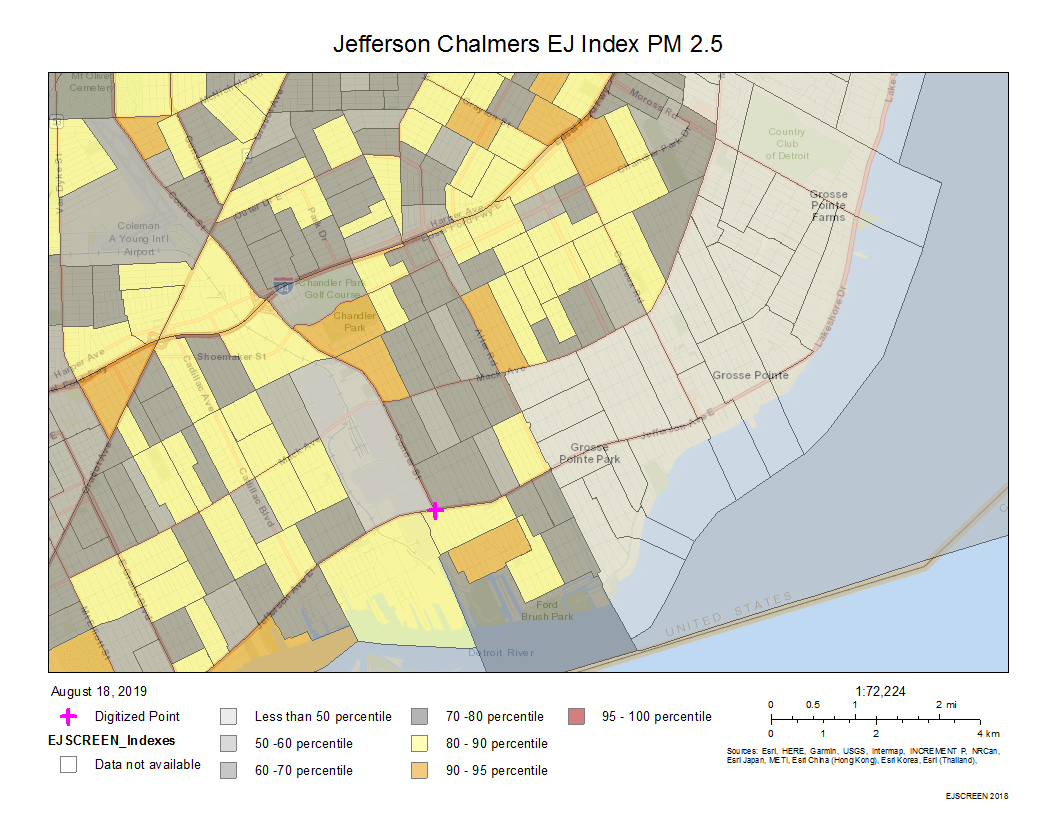

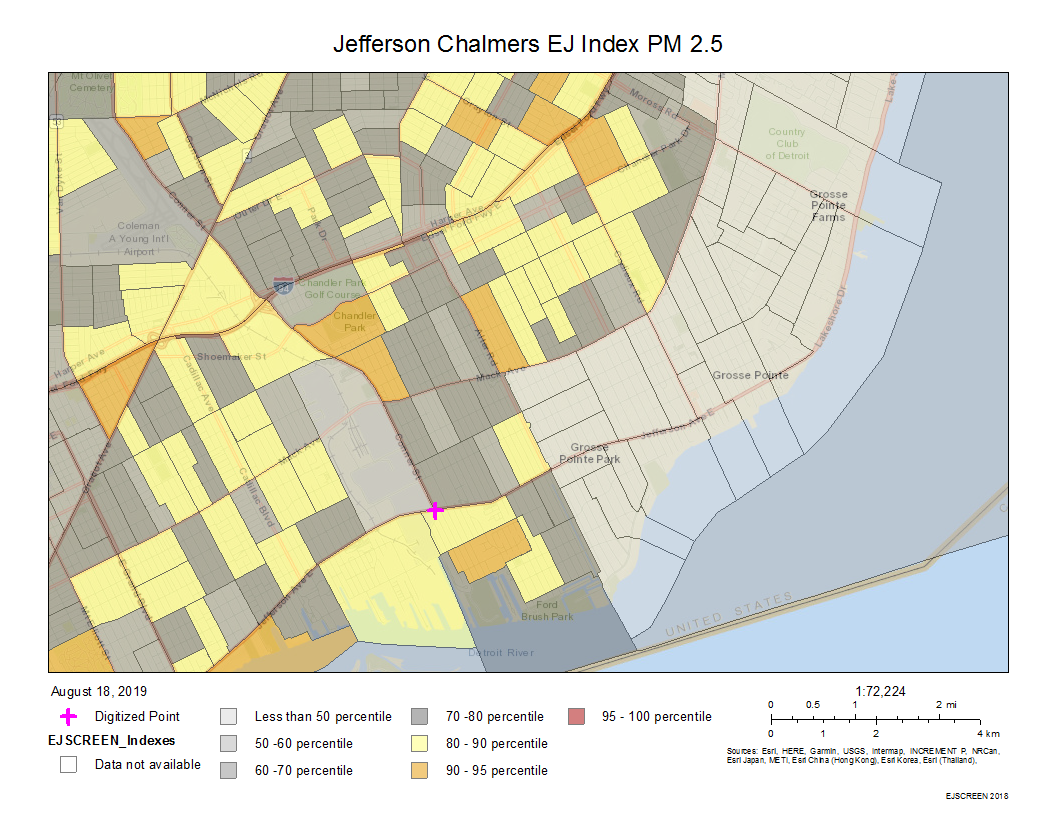

Environmental justice index for particulate matter in the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood (U.S. EPA's EJ screen tool)

Environmental justice index for particulate matter in the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood (U.S. EPA's EJ screen tool)

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is working with the City of Detroit to secure funding to provide technical assistance on “risk reduction alternatives,” and to identify long-term solutions to flooding in Jefferson Chalmers, according to Jim Luke, Outreach Coordinator for the Detroit District of ACOE. But this work is still in the early stages.

In April, just as the canal flooding was getting underway in Jefferson Chalmers, the city released its neighborhood plan for the district, filled with ambitious plans for waterfront access, housing stabilization, and rejuvenated retail. “I don’t see how you can invest in the Jefferson Chalmers area with new housing, new businesses, new green space without really having a serious look at a sea wall,” says Givens. “A lot of what we’re doing in our city planning, it seems, is based on not recognizing conditions for what they really are.”

Jefferson Chalmers is a case study for how equity, climate vulnerability, and resilience interact. The area has elevated environmental justice indices for a range of contaminants including particulate matter (2.5), according to EPA data. A new Fiat Chrysler assembly plant is expected to bring more jobs, but also more pollution, to the area.

And, as in many older urban communities across the Great Lakes, water (un)affordability and shut offs are a challenge. An analysis of city data showed that 7.6 percent of homes in Jefferson Chalmers had their water shut off over unpaid water bills in 2016. A more recent analysis showed that shutoffs have continued across the city, albeit at a lower rate. And electric utility affordability is rapidly becoming a concern as DTE Energy, the region’s electric utility provider, seeks to increase rates, even as reliability takes a nosedive.

Add to that list the neighborhood’s vulnerability to flooding, heatwaves and cold snaps, and Jefferson Chalmers becomes a sort of microcosm for studying climate inequity. A 2012 University of Michigan project mapped areas of heat and flooding by census block group, showing that parts of Jefferson Chalmers were among the most vulnerable areas in the city.

“The utility burdens for people in Detroit are extreme,” says Justin Schott, executive director of the energy efficiency nonprofit EcoWorks, a member of a cross-disciplinary group of University of Michigan researchers teamed with community organizations called the “Heatwaves, Housing, and Health (HHH) Partnership” that is working to study climate vulnerability in Jefferson Chalmers. “If you look at a household of three at one hundred percent of poverty level, they have an income of $20,000 a year, and they have an average energy and water bill of something like $3,500 a year, which is eighteen percent of their total income. It’s a huge part of housing affordability that doesn’t get talked about enough.”

All of this is taking place within the larger context of a push for economic revitalization in Jefferson Chalmers. In 2016, the neighborhood became the first site in Michigan to gain National Treasure status from the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It has since become a focus of the City of Detroit’s $100 million “Strategic Neighborhood Fund 2.0” effort, which intends to bring intensive planning and development into targeted neighborhoods. Jefferson East Inc., a business development organization, has ramped up its efforts in streetscaping and green infrastructure. New businesses have opened, including Caribbean-inspired Norma G’s, the first new restaurant in the district in decades, which was also listed as one of the top new eateries in the city in 2019. Renovations of apartment buildings and commercial spaces are in progress.

But as development picks up, some neighborhood residents are expressing concern about displacement. Linda Lewis is a lifelong resident of the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood. She said she’s seen wealthy people from Seattle and New York come into the neighborhood to buy up city-owned land in recent years, often parcels she says local residents have tried and failed to purchase from the city in the past.

“We’re looking for redevelopment without being displaced,” says Lewis. “It’s no problem that they want to fix up this neighborhood, that’s wonderful. But we who have lived here for years would like to benefit from it. We have businesses. We’d like to buy some of this property in this area that we live in.”

Detroit Blooms on Manistique Street in Jefferson Chalmers (Nina Ignaczak)

Detroit Blooms on Manistique Street in Jefferson Chalmers (Nina Ignaczak)

The convergence of these challenges is one reason why researchers from the University of Michigan have taken an interest in the area. In 2016, HHH began studying how housing characteristics, demographics and behavioral factors contribute to climate-related morbidity and mortality in Detroit neighborhoods, including Jefferson Chalmers.

The team studied the living conditions and habits of residents in three Detroit neighborhoods and found an association between not having air conditioning and heat related illness among people who had lived in their homes for at least five years. Now the researchers are embarking on a new project that is borrowing a page from social work. The HHH coalition is studying whether “sustainability case managers” can make a difference in health outcomes by assisting vulnerable residents in accessing available resources and programs for energy efficiency, as well as how temperature affects short-term changes in cognition and sleep quality.

On a humid evening in late July, the UM researchers hosted about two dozen neighborhood residents in a non-air-conditioned community room of Hope Community Church. They shared information about their study and offered $25 to residents who agreed to participate. To get the money, the residents needed to sign a research participation form and a form authorizing DTE Energy to share their utility bill with the researchers. They also needed to take a survey on their home characteristics and behaviors, and agree to install a temperature monitor in their homes. Those who agreed to attend a final study meeting would receive another $25.

Tony Reames, an assistant professor in the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan and director of the Urban Energy Justice Lab, is one of the researchers. “What we’ve learned in previous studies is that people don’t know the different programs; people feel overwhelmed about going through the process,” he told me. “And so we believe that having the human element to this will amplify the efficacy of the programs.”

The researchers hypothesize that having a case manager focused exclusively on utility issues will make an impact that is beyond the scope of typical health and human services. “We think it’s difficult for case managers that are also dealing with food assistance and housing and transportation assistance to also help with energy efficiency,” says Schott. “And so we’re looking at how much we can maximize the benefits of assistance programs, in particular looking at reductions in energy and water consumption, which we think are the most important to get to an affordable level of utility bills.”

Another challenge is helping residents parse the information they receive and stay away from utility fraud, predatory programs, and scams. “We get so much information coming to us from all sides,” says Michelle Alford, who will be working with some of the study participants to provide case management. “So one of the priorities is deciphering who is on the side of good, transparent, knowledge-based, communications, versus the people who go door to door.”

Kim Carter, one of the residents at Hope Church, had once fallen victim to one of these scams. Her utility bills went up “drastically” after she signed a contract with a third-party provider who promised a cheaper gas rate, but didn’t tell her that she would still have to pay DTE Energy for use of its infrastructure. She’s also taken advantage of DTE Energy’s energy efficiency programs, which implemented measures such as wrapping basement pipes and installing energy efficient light bulbs, but she says those strategies haven’t made much of a dent in her bills. What she really needs help with, she says, is insulation for the entire house. But because her income is above the poverty line, she says she is not eligible for programs that might help her.

Reames acknowledges that people in Carter’s income bracket often fall through the cracks. “People in that moderate income gap don’t qualify for the low income programs because they make too much money, but they don’t necessarily have the money to pay for these improvements on their own. So that’s a gap in policy, but it’s also a gap in some of our studies that focus on lower incomes. Hopefully part of this study is that there is a group of people that actually participate in the energy efficiency workshops and have the caseworker to help them get into the programs and actually get the measures implemented. And so we do hopefully see some energy and water savings.”

But Carter and several other residents voiced suspicion and frustration about the study during the meeting. “I’m still struggling. I don’t mind these studies, but these studies aren’t really doing anything for me here and now,” says Carter. “I just hope they can get something to actually help people.”

Black’s group is not waiting for the results of any studies before taking action. She’s currently working on a project to install solar panels on twenty-two owner-occupied homes within the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood, including her own. “We realized that the neighbors in this community were experiencing high costs in energy,” she told me. “So we were looking for alternative sources of energy that can be sustainable throughout the neighborhood.”

Black hopes the homes will have solar panels installed by spring of 2020. To implement the program, she is working with Brandon Knight, president of Distributed Power LLC. She first met Knight when he helped establish the solar-powered charging station in the neighborhood. Knight’s company has designed and built more than one hundred grid-connected residential solar arrays across the metro Detroit region over the past year using a loan product that keeps payments at or below a resident’s current utility rates. He’s working to implement this program in Jefferson Chalmers at scale, further reducing costs. Black and Knight are also working to incorporate energy efficiency into the program.

Tammi Black poses at the site of her future solar array behind her home in Detroit's Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood (Nina Ignaczak)

Tammi Black poses at the site of her future solar array behind her home in Detroit's Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood (Nina Ignaczak)

“Working with twenty-two houses all at once, we can get equipment from our suppliers at a good price. And we’re willing to do the installs at a discount because we’re able to do the same project essentially over and over and over again,” says Knight. “So the volume and the repetition and consistency in design, so that we only had to do one electric diagram that we’re able to apply to every project, reduces the costs.”

The first step, says Knight, was getting all of the residents registered before a May deadline that grandfathered them in under Michigan’s “old” net-metering law. The state’s net-metering program was abolished in May; the new law governing grid-connected solar, approved by the Michigan Public Service Commission in in a rate case filed by DTE Energy, introduced a new formula that is less favorable for residential solar. The MPSC also approved a rate hike for customers. The combination of these decisions is expected to significantly increase the time it takes for residents to recoup their investment.

According to Knight, it is still more economical to remain connected to DTE Energy’s grid right now. But as climate and economic conditions change, there may come a day when residents find it more cost effective to disengage from the grid entirely.

It’s a day Patricia Jones, one of the members of Black’s Women of Empowerment group, is looking forward to. She says she pays between $300 and $400 per month on her energy bill and won’t turn the air conditioner on unless it is really hot. “To get off of DTE, I will look at it like a real bad divorce,” says Jones. “So when I go off the grid, I’m having a divorce party. I want to tear up my last bill, I want to tell them right then and there we’re done. I don’t want any alimony.”

Flooding aside, something has happened on Manistique in the past decade. The city’s demolition program has torn down many of the vacant homes here. A flower farm, Detroit Abloom, covers several vacant lots. An urban farm called Feedom Freedom, created by Manistique resident Myrtle Curtis, has been thriving here since 2009. Adjacent to Feedom Freedom is the new Fox Creek Artscape, a Kresge Foundation-funded project which combines art with a farm stand and community gathering space that launched in June.

Across from Black’s home is the Community Treehouse Center, a project, led by Black, that will create an ADA-compliant community space. Black’s organization received a planning grant of $35,000 in 2018 and an implementation grant of $150,000 in 2019, both from the Kresge Foundation, to build out the project. The goal of the complex is to offer “horticultural therapy” to relieve anxiety and depression. Adjacent to the treehouse site is a “Creative Empowerment Garden”, which includes a solar installation that serves to demonstrate the benefits of solar power (residents can charge their phones on it) and doubles as an outdoor movie venue.

As climate change ramps up, low-income communities and communities of color, especially majority-Black communities, are experiencing the brunt of its effects, a result of compounding environmental, geographic, and socioeconomic factors. In Detroit, heat and flooding are two of the most significant environmental factors. Work is underway to relieve utility burdens and manage floods. But institutions can move slowly, and it’s too early to know what the outcome of that work will be.

In the meantime, temperatures and waters keep rising, and community members like the Women of Empowerment are taking matters into their own hands. “All of the projects that we’re doing in our community in the areas that used to be blighted are to help with our wellbeing,” says Black. “So I think that’s the excitement for me, that everything that we’re doing in the community will help benefit us.”

Home on Ashland street in Detroit's Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood recently installed solar panels as its basement flooded with water from the Detroit River (Nina Ignaczak)

The "Women of Empowerment" meet at Tammi Black's home in Jefferson Chalmers (Nina Ignaczak)

Environmental justice index for particulate matter in the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood (U.S. EPA's EJ screen tool)

Detroit Blooms on Manistique Street in Jefferson Chalmers (Nina Ignaczak)

Tammi Black poses at the site of her future solar array behind her home in Detroit's Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood (Nina Ignaczak)