Infrastructure in

America

Stopping Veolia: A Report from Seattle

When our small group of activists began resisting the privatization of Seattle’s municipal transportation system in 2012, we were confronting a corporation whose power was not to be taken lightly. Veolia has deep imperial roots, and boasts a genealogy that mirrors the development of neoliberal economics. The history of Veolia, under its many monikers and subsidiaries, reaches back over a century and across oceans. From Compagnie Générale des Eaux (CGE) to Vivendi, and later, the French-based multinational holds contracts on five continents,1 specializing not only in water and sanitation, but also in trash and transportation.2 Veolia is one of the largest privatizers of public services globally and, by revenue, the world's largest privatizer of water.3

Stop Veolia Seattle (SVS) is a group formed in response to King County, Washington’s contract with Veolia for the operation of Metro Access paratransit. Veolia’s history of union busting, inadequate service, and participation in global structures of inequality motivated communities around Seattle to urge King County to discontinue its contract. SVS built relationships between local labor and disability justice communities, and groups working on anti-corporatization, water rights, environmental justice, Palestine solidarity, and global anti-imperial movements. It wanted to connect global solidarity to local activism in ways that renewed energy and nourished communities. Resisting Veolia, with its hydra-like planetary operations, demands the construction of a deep, relational, and well-researched coalition of mutual aid.

Understanding Veolia’s story from the beginning is essential for this task. Building a history of the company's origins, development, and expansion uncovers evolving ideologies of capitalism and imperialism that facilitated its early expansion, as well as provides a more recent map of the frontlines of neoliberal privatization. It also reveals the presence of communities around the world that have been fighting back throughout Veolia's last few decades of corporate shapeshifting. Understanding the continuities between old and new forms of power and inequity can, perhaps, continue to move local communities toward increasing, enduring, new, and global solidarities strong enough to dismantle “water apartheid” in the face of climate disruption.4

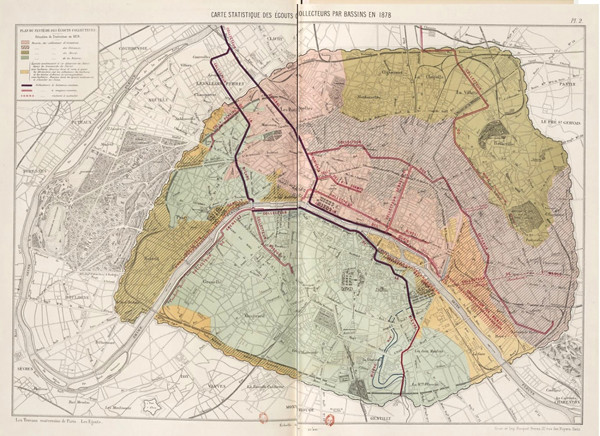

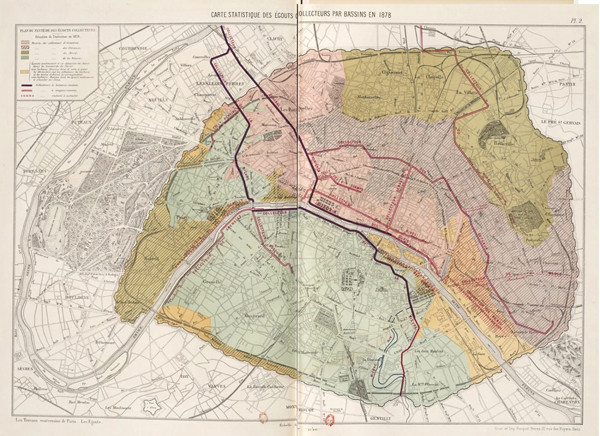

Map of Paris's sewers in 1878. Source: Crystal Bennes

Water & Empire

Compagnie Générale des Eaux (CGE)—the first of Veolia’s many incarnations—was born with an imperial decree of Napoleon III on December 14, 1853.5 Just over a year before CGE’s founding, Napoleon III had declared himself Emperor of France in a coup d’état. Unable to serve a second term as president under the new constitution, and unable to gain support for a constitutional amendment, he took power by force, becoming the leader of France's Second Empire.6

The Second Empire was a time of rapid and unprecedented economic expansion. Industrial production doubled, foreign trade tripled, and railway mileage expanded six-fold. The first large investment banks were founded at this time, as was the first department store. The French merchant marine (all non-Navy commercial ships used in trade) became the second largest in the world as Napoleon III negotiated what is considered the first modern free trade agreement, the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty with England.7

With both authoritarian and liberal-reformist tendencies, Napoleon III is domestically known for his massive public works projects that define the modern urban-scape of France today. He is also remembered for severe restrictions on civil liberties, censorship laws, and the harsh repression of opponents. CGE’s first contract was to supply water to the public of Lyon for one hundred years. The company grew quickly, and in 1861, was awarded a fifty-year concession for water distribution in the city of Paris.8

CGE’s founding president, Count Henri Siméon, was a political leader of the Elysée Party, which had officially approved Napoleon III’s 1851 coup. One year later, the Count presided over the merger that founded the Lyon-Mediterranean Railway Company. In the year of CGE’s founding, Siméon was also presiding over a city planning commission to write the new master plan for the city of Paris, which would later be implemented by Georges-Eugène Haussmann. The growth and influence of French capital was simultaneously reaching across borders, with bridges, railways, and sewage systems being built with French money and engineering throughout continental Europe. Veolia’s promotional history often cites CGE’s centrality to this era of industrialization and urbanization.

Fervor for private industry was developing in the context of a growing empire that came to include not only colonies in the West Indies and South America, but also Algeria, and under Napoleon III, parts of present-day Vietnam and Cambodia. Napoleon III actually doubled the area of French colonial holdings with a patchwork of colonies, protectorates, and military bases. A year after CGE’s founding, Napoleon III was embroiled in the Crimean War, and by 1900, France was the world’s second-largest colonial empire.9

Some of the largest businesses in France, including CGE, were profiting from ventures both at home and in the colonies. After its merger, which was presided over by CGE’s president, the Lyon-Mediterranean Railway held contracts for railway operation in both the southeast of France and Algeria. Like the railroads, a potent symbol of colonization for many in the Global South, Napoleon III was consolidating and expanding water and sanitation infrastructure. Sewage treatment and filtered water systems were understood at the time to be the same kind of profitable new market as railways.

As one of the first private companies to operate municipal water systems in France, it did not take long for CGE to expand in its own right beyond the nation’s borders. In 1880, CGE was awarded its first international contract, in Venice. In the next three years, imperial trade routes took CGE to Constantinople (Istanbul) and Porto. CGE’s reach stretched further and further afield, moving deeper and deeper into the lives of the colonized.

Compagnie Générale des Eaux drinking water plant in Neuilly sur Marne, France, ca. 1958. Source: Veolia.

Compagnie Générale des Eaux drinking water plant in Neuilly sur Marne, France, ca. 1958. Source: Veolia.

Becoming Veolia

For over a century, CGE remained largely focused on water. In 1953, its centennial year, CGE was selling water to eight million people in France, almost nineteen percent of the country’s population. The appointment of Guy Dejouany as CEO in 1976 marked a shift for the company. A series of takeovers in 1980 extended its reach into the fields of waste management, energy, transportation, construction, and property. CGE’s transformation began with the merger of a number of different subsidiaries into Omnium de Traitement et de Valorisation (OTV). OTV specialized in the design, engineering, and manufacture of water and wastewater treatment equipment. CGE then began acquiring controlling interests in a variety of transit-related companies, including the Compagnie Générale d’Entreprises Automobiles (CGEA), which specialized in industrial vehicles, and Compagnie Générale Française de Tramways (CGET), which later divided into two branches: Connex and Onyx. CGE also expanded into energy services around the same time, acquiring both the Compagnie Générale de Chauffe and the Montenay group, which was later renamed Dalkia.10

In 1983, CGE supported the founding of Canal+, the first Pay-TV channel in France. In 1988, CGE purchased the French concessions and construction company Société Générale d’Entreprises SA (SGE), later VINCI.11 VINCI is one of the largest construction companies in the world today by revenue, operating municipal projects and services in over one hundred countries.12 Throughout the 1990s, CGE further expanded into telecommunications and mass media, culminating in the 2000 merger that produced Vivendi Universal and Vivendi Environnement.

Under the leadership of Henri Proglio, the 1990s was a decade of rapid expansion as well as scandal and mismanagement at CGE. Most notably, in 1996, over one-third of the directors of Vivendi Universal’s main board were under investigation for corruption. The company scrambled to jettison its debt load with the reduction of Vivendi Universal’s credit rating to “junk” status and the forced resignation of its CEO, Jean-Marie Messier. Messier was later convicted and fined in France for fraud as well as by the US Securities Exchange Commission, and denied a $25 million severance package.13

In 1998, CGE officially changed its name to Vivendi, and in 1999, Vivendi Environnement was founded to consolidate Vivendi Water (Water), Onyx (Waste Management), Dalkia (Energy) and Connex (Transportation).14 In 2002, Vivendi Universal sold off a majority stake of Vivendi Environnement, and in 2003, renamed it Veolia Environnement. Finally, in 2005 the company's four divisions—water, environmental services, energy, and transportation—adopted a single name: Veolia.15 With a new name and logo, Veolia maintained hundreds of subsidiaries in dozens of countries as Veolia Water, Veolia Environmental Services, Veolia Energy, and Veolia Transport, as well as others, such as US Filter,16 Apa Nova,17 PVK, Onyx, Dalkia, and Connex.

The early 2000s saw Veolia continuing to battle debt. An initial strategy of competing for large urban utilities gave way, particularly in North America, to targeting smaller communities with less regulation, legal oversight, and competition, allowing Veolia to avoid capital commitments and performance guarantees.18 Veolia also shifted toward a consultancy model, building relationships with local governments and industries that could be extended into management contracts.19

In 2012, Veolia’s current CEO, Antoine Frérot, introduced the company’s vision of the future as targeting Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, as well as expanding into “new markets” such as shale gas extraction and the dismantling of nuclear facilities.20 A year later, Veolia was awarded the contract for the disposal of Syrian chemical weapons.21 Also in 2013, the Iraqi Ministry for Municipalities and Public Works signed a $115 million contract with Veolia to build a desalination plant in southern Iraq.22 Veolia’s 2014 annual report highlighted major water contracts in Japan and Ecuador (through another new subsidiary, Proactiva, which operates in eight South American countries), as well as contracts for a water treatment plant for Shell’s Carmon Creek, a heavy-oil project in Alberta, Canada, and the design of a desalination plant for a Saudi petrochemical complex.23

Veolia has built up a track record of mismanagement with environmental and human consequences.24 One recent example was in 2012, when the town of Gladewater, Texas found that Veolia had violated federal water quality standards sixteen times there since 2004.25 Residents had long complained about the color and smell of their drinking water, but the situation escalated in 2012 when councilmembers discovered that the town was close to “running out of water” one day in August. Left with only 40,000 gallons of water in a one-million-gallon clear well, the water level should have set off an alarm because of the risk to the community if a fire or line break occurred. Government officials cited Veolia’s lax oversight and staffing with no full-time manager at the plant.26 Other recent examples include in 2013, when Veolia was implicated in excesses of cancer-causing liquid benzene in the water supply of 3.6 million people in Lanzhou, China,27 and in 2016, when the Michigan Attorney General filed charges against Veolia for its role in the lead poisoning of Flint, Michigan’s water supply.28

Today, Veolia describes themselves as “specialists in the management of utilities and infrastructure assets,” identifying their core markets as the automobile, chemical, steel, pharmaceutical, food and beverage, and defense industries.29 Their “specialty brands” include Nuclear Solutions, Seureca, Water Technologies, 2EI, and Industries Global Solutions.30 Veolia Water Technologies alone claims over 80 locations worldwide.31

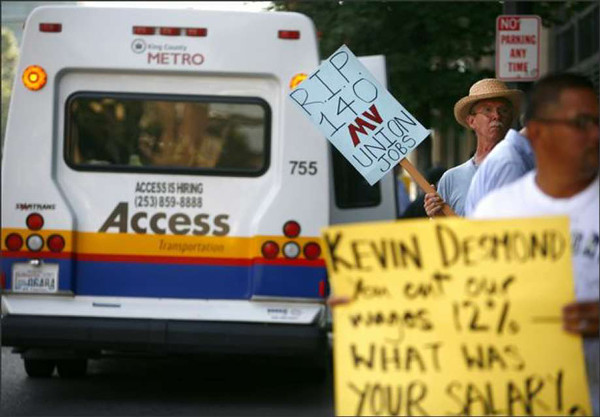

Protests in Seattle over the privatization of accessible public transit Metro Access, 2008. Source: Maia Brown.

When Veolia Comes to Town

In Seattle, we first came to know Veolia through their transportation division, where we saw how the privatization of public services and infrastructure, whether water, waste, or transportation, share similarly troubling trends. In his article, “Sweatshops on Wheels,” Chris Hedges outlines these dynamics in the United States where a political culture of economic austerity and neoliberalism meet to starve or dismantle social services, and in particular, public transit: “This process of destroying our public transportation system is largely complete…. But an even more insidious process has begun. Multinational corporations, many of them foreign, are slowly consolidating transportation systems into a few private hands.”32

Veolia Transportation (now Transdev) is one of the largest private providers of mass transit in North America. Their website boasts that “an increasing number of transit agencies have realized that they are unable to maintain service levels with decreased funding for their transit systems, and contracting with the private sector for all or part of the service can be an alternative to layoffs and service cuts.”33 In other words, as municipalities reduce or do away with transportation subsidies, transit agencies must rely on employee pay reductions and fare hikes for riders. When politics makes these austerity measures difficult to implement, private operators like Veolia are often brought in to slash wages and benefits on local governments’ behalf. But of course in return, these private operators expect a profit.

In reality, Veolia’s promised cost reduction typically translates to an increase in service fees while the services themselves actually shrink: routes are cut on bus lines, infrastructure is often neglected, maintenance deferred, and substandard equipment used. More often than not, unions are busted and working conditions become untenable. Like other privatizers, Veolia’s municipal contracts experience high turnover, failing to attract skilled staff with conditions of impossible scheduling and minimal breaks, low salaries, and the dissolution of benefits and pension plans. In addition, the fine print of Veolia contracts often skirts full liability. In the words of the international human rights organization Global Exchange: “Worldwide, consumers report that Veolia consistently charges high rates, provides poor service, and fails to make promised improvements.”34

According to organizations like Food and Water Watch, Veolia often underbids its competitors for the operation of municipal utilities and transportation systems. As an example of what Naomi Klein terms “disaster capitalism,” it was Veolia that took over the New Orleans bus system after Hurricane Katrina, immediately stripping workers of their pensions.35 In New York, Veolia hired former Senator Al D’Amato as its lobbyist in order to take over Nassau County’s bus service from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Months after taking over the contract, Hurricane Sandy became a convenient pretext for the implementation of planned service cuts that disproportionately affected poor riders.36

The mercenary role of corporate transit operators further insulates governments from political accountability for urban inequality and its intersections with structural racism. The discriminatory provision (and defunding) of transit services deepens under corporatization to keep up with the demand for higher profit margins. Multinationals become the proxy force for the structuring and control of public mobility—the demographic (re)mapping of urban space by virtue of a weakened, unequal, and for-profit public transportation system.

Veolia first came to Seattle in 1996 for the partial operation of the King County paratransit system. Known as Metro Access, the service was created to respond to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) mandate for accessible public transit. In spite of protest, in 2008, Veolia took over a larger share of Metro Access.37 As a result, 140 drivers were sacked and had to reapply for their jobs with limited benefits and without the protection of a union, earning less than they had before negotiating a pay increase a year prior.38 The disability justice community was not satisfied with Metro Access’s service under Veolia, and the Amalgamated Transit Union Local 587 (ATU) tried to reunionize paratransit drivers under Veolia unsuccessfully. And in 2011, Veolia was awarded a seven-year extension until 2018.39

Stop Veolia Seattle (SVS) began within this context. A Ride-Free-Zone between downtown stops—a lifeline for low-income and homeless riders—had recently been discontinued, and a fresh fare increase had been implemented across the board. With the building of a new light rail system, longstanding and relied-upon bus routes were being renegotiated and cuts discussed. Metro Access was in the middle of heated contract negotiations and arbitration with the ATU, and the Transit Riders Union, an independent union of transit riders organizing for better public transit, was gaining momentum in public and political discourse.40

Our small working group was formed around 2012, made up of people with backgrounds in water justice and work on the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, as well as others who were just coming out of Occupy and student-custodial-worker solidarity networks at the University of Washington.41 The Marseilles Declaration for Palestinian Water Rights had launched at the 2012 Alternative World Water Forum, and there was particular interest to find a fulcrum in Seattle for shared and intersecting concerns.42 We knew that through another subsidiary, Veolia was operating transit for illegal Israeli settlements and the Tovlan landfill in the occupied Jordan Valley in the West Bank—a landfill that illegally annexed Palestinian land to process waste for the illegal settlements in the area, as well as for trash transported from within Israel.43 In very concrete ways, Veolia was involved in the building and operating of the infrastructure of occupation, creating the often quoted “facts on the ground” that make the occupation of Palestine an increasingly permanent reality.

We wanted to find ways of breaking the city’s contract with Veolia, focusing primarily on building a coalition to prevent a renewal of the county’s contract in 2018. We met with ATU leadership as well as council members, and collected testimonials from Metro Access users.44 We used the history of Veolia to connect existing coalitions and build new relationships with those already organizing a black-led movement to stop the construction of a new youth jail and Latinx and solidarity movements opposing the Trans-Pacific Partnership. We also knew we were joining a long conversation on corporatization and militarism, as well as established movements targeting Veolia specifically. We wanted to document that scope and our position within it, and worked to create a map of intersections and solidarities overlaying Veolia’s ever-changing map of abuses.45

As a result of our activities, in 2014, the King County Labor Council—the local affiliate of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), which represents over 150 labor organizations—unanimously passed a resolution to end all contracts with Veolia, to preclude Veolia from future contracts, and to bring Metro Access in-house.46

A significant turning point came later that year when we received access to Veolia's contract with King County. Instead of the savings Veolia had promised, the County had signed contract changes approving the allocation of an additional $7 million in annual costs and significant reductions in both driver training hours and vehicle maintenance.47 Further, we found that the County had received a letter from Veolia mischaracterizing its merger with transportation privatizer Transdev as merely a “name change and rebranding process” with “no changes in ownership, in management, or in any other aspect of our operations.”48 After Veolia’s merger in 2011, its restructuring in 2013, and name change in 2014, Transdev was, in fact, a new company that had not existed when Veolia signed its contract with King County.49 We believed this was a fraudulent misrepresentation and could be a breach of contract that should reopen Metro Access to a public bidding process.50

In response to these new findings, in 2015, Larry Phillips, Chair of the King County Council, sent a letter to King County Executive Dow Constantine signed by the five Democratic members of the nine-person council. The letter urged Constantine to investigate “serious concerns for many aspects of Access service, including rider experience, labor protections and wages, and potential cost overruns to our government.”51

Veolia/Transdev wrote a letter on April 6, 2015 to the County Council and Executive warning councilmembers that they were unwitting allies to ATU's “misinformation” and that Stop Veolia Seattle was a “local front organization” of “anti-Israel activists.”52 Though many in the union were uncomfortable with BDS and wary of more internationalist politics, the leadership did not hesitate to respond. In a letter written a week later to the Council and Executive, ATU called Veolia/Transdev’s letter a “spurious effort to distract from its lackluster performance record” and defended coalition work with SVS.53

After these gains, SVS largely dissolved as a working group while the coalitions we had been part of re-animating continued. In November of 2015, Veolia/Transdev drivers voted to unionize and joined the Teamsters, one of the largest and most powerful unions in the country. They ratified their first contract with Veolia/Transdev in 2016 with ninety-four percent approval. In addition, drivers secured an agreement with the county stating that any new contract after 2018 must include everything the new union had just negotiated.54 In 2018, Metro amended the Access contract requirements for future bids.55 In its online publication, Metro said: “We are pleased that the amended RFP has a stronger focus on performance, accountability, equity and social justice, customer service, continuous improvement” and committed to bringing the customer-service wing of Access in-house.56

At the beginning of 2019, Metro entered negotiations with MV Transit,57 and in an email to the author, confirmed that "Veolia would not take over the Access contract starting August 1, 2019.”58 Ironically, MV Transportation held the contract before Veolia. Specializing in paratransit, MV Transportation is a historically Black-owned business based in Dallas, Texas, with contracts in the US, Canada, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Brazil.59 MV Transportation is also a large private transportation corporation with a mixed track record with labor, but it is still preferable to Veolia.60

After many years, this is both an incredibly significant and an only partial victory. What our organizing proved was that Veolia could be taken on and taken down, and that a campaign highlighting both local and international abuses could ultimately succeed without censoring members of our coalition. Over the years we were organizing, the BDS movement in particular was gaining traction and putting very real pressure on Veolia’s activities in Israel.61 Veolia claims to have divested its operation of segregated bus lines and the Jerusalem Light Rail in 2013.62 And in 2015, Veolia announced it was pulling out of all contracts with Israel.63

BDS logos targeting Veolia.

Resourcing the World

It will take a profound structural change to ensure climate change adaptation does not lead to even worse forms of water apartheid than currently exist.

—Patrick Bond64

Under the tagline “resourcing the world,” Veolia has branded themselves as “resourcers.”65 Recognizing the new markets that climate disruption introduces, in their annual “Sustainability Performance Report,” Veolia now describes their work supporting municipalities and businesses to adhere to new environmental standards by avoiding and reducing carbon emissions, recycling hazardous waste, and benefiting from Veolia’s assessments and research into cleaner energy options and biodiversity.

In 2017, Veolia was added to the Dow Jones Sustainability index, and in 2018 was listed with “Gold Class” status on RovecoSAM's Sustainability Yearbook.66 In 2018, Veolia was present, and in many cases presented, at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP24) and Sustainable Development Goals Summit, as well as the Global Water Summit and World Economic Forum. These invitations endorse and normalize the private sector’s role in international policy, giving a platform for corporations to set agendas as well as to shape ideologies and approaches to urgent questions of the future in ways that prioritize their profit. The CEO Water Mandate, a UN Global Compact initiative launched in July 2007, is a particularly terrifying example of this. In this public-private initiative, corporations including Veolia, Suez, Nestlé, and Coca-Cola sit in positions of influence over global water policy in a clear conflict of interest.67 Veolia’s role in these initiatives is, if nothing else, cynical.

In 2017, Veolia was given a water treatment contract by the fracking giant, Antero Resources, for their Clearwater site outside of Pennsboro, West Virginia, to treat “waste with a low level of radioactivity.” The Antero site has already been a source of controversy and worry for the local community.68 In another project in the region, Veolia now manages all utilities for DuPont's largest facility in the US—a coal-fired plant in Richmond, Virginia.69 In their 2018 report, Veolia highlighted their collaboration with Suez (one of Veolia’s biggest competitors in water privatization) for the design, building, and operation of a water production plant servicing 4.3 million people in Dhaka, Bangladesh.70 Bangladesh is facing depleted aquifers, and Veolia's contract means that solutions to potentially avert a dire future water shortage are being managed for a profit.

2018 marked the last year of Veolia’s latest strategic plan, the predecessor of a 2011–2015 “transformation plan” that began a process of “recovery in revenue growth” after Veolia’s struggles with debt in the early 2000s.71 Wrapping up 2018 and looking to the future, CEO Antoine Frérot recently announced plans for “small-scale bolt-on acquisitions” in order to “extend [Veolia’s] lead in environmental businesses.” He further identified the “seeds” of Veolia's new activities: “microgrids, urban agriculture, air quality.”72

While noting their troubling resiliency, it is worth remembering the ways Veolia has been put on the defensive.73 Between 2006 and 2012, there were nearly fifty documented campaigns successfully targeting Veolia that spanned four continents.74 Even in France, communities were taking back their water systems: in 2009, after a twenty-five-year contract, the city of Paris decided not to renew its contract with Veolia. Paris has since saved money and stabilized the price of water. In the rest of Europe, including Belgium, Germany, and Romania, and elsewhere around the globe, municipalities have broken contracts with Veolia and restored public control of their water.75

There is also resistance from within. In 2013, a Veolia Water employee in Avignon lost his job for refusing to cut the water off for families who could no longer pay their bills. In an interview with Europe1 Radio, Marc (only his first name has been made public) said, “It could happen to anyone. You have to make a choice—either feed the children or pay the bills. These big companies pocket the money and redistribute it to their shareholders, without looking after their clients or employees. It’s scandalous.”76

In the United States, between 2003 and 2012, Veolia lost fifteen government contracts, representing nine percent of its total across the country.77 One of Veolia’s largest losses in the United States came in 2010 when the city of Indianapolis decided to exit a twenty year, $1.5 billion water contract more than a decade early, selling the water utility and sewer system to the non-profit Citizens Energy Group. When Veolia (then US Filter) first took the contract in 2002, retirement plans of non-unionized workers were cut, consumer complaints doubled, and because of a lack of proper safeguards, a typo by one employee caused a boil-water alert for more than one million people, temporarily closing local businesses and keeping 40,000 students out of school.78

In Canada, a coalition is currently bringing together The Council of Canadians, the Common Front for Social Justice, the Moncton and District Labour Council, the New Brunswick Federation of Labour, and CUPE New Brunswick to campaign for de-privatizing Moncton's municipal drinking water treatment plant at Turtle Creek. Veolia's Moncton contract expires in December 2019.79

Veolia is just one way to understand the need for solidarity in struggle, as well as how corporatization entangles people across the planet with past and present histories of oppression. With a better understanding of the continuities between early structures of Western imperialism and industrialization and today’s neoliberal globalization—exemplified by Veolia—comes a strengthened ability to build new communities of resistance. Understanding this should not only affect the ways communities and policymakers think about combating privatization, but also how to work toward alternatives to corporatization. Language and history matter: Are we fighting for legal protections as customers, or are we fighting as water protectors? It is worth asking whether a rights-based framework is expansive enough to face what lies ahead. In the words of activist scholar Patrick Bond, the question remains: how can we “transcend the individualist and consumerist orientation of the ‘right to water’ narrative, and move to a ‘commons’ approach?”80

- 1Africa/Middle East, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and North America.

- 2Veolia Group’s 2018 Annual Report boasted almost 171,495 employees; control of 95 million people’s drinking water and 43 million people’s waste collection service worldwide; the production of almost 46 million megawatt hours of energy and 49 million metric tons of treated waste. Veolia operates 3,603 drinking water facilities and 2,667 wastewater treatment plants; 655 waste processing facilities and 2,389 industrial sites. The Group ended the year with a consolidated revenue of €25.911 million. https://www.veolia.com/en/newsroom/publications.

- 3Bluefield Research, “Veolia Water Strategy: Break Down Global Market Positions,” March 12, 2019, https://www.bluefieldresearch.com/research/veolia/.

- 4Patrick Bond, “Durban’s Water Wars, Sewage Spills, Fish Kills and Blue Flag Beaches,” in Durban’s Climate Gamble: Trading Carbon, Betting the Earth (Pretoria: University of South Africa Press, 2011), 77.

- 5Veolia, “160 Years of History,” https://www.veolia.com/en/veolia-group/profile/history-veolia.

- 6Encyclopedia Britannica, Fifteenth Edition, 1991, 513.

- 7Ibid., 513.

- 8Veolia, “160 Years of History.”

- 9Encyclopedia Britannica, 513.

- 10Veolia, “The history of Veolia: 1950–2000,” https://www.veolia.com/en/veolia-group/profile/history/1950-2000.

- 11Veolia maintained ownership until 2000. VINCI has been involved in a number of scandals globally, most prominently the 2016 demolition of a refugee encampment in Northern France of asylum seekers attempting to cross into Britain associated with their contract to build a £2.3 million-pound border wall. See “VINCI, Company Profile,” Corporate Watch, https://corporatewatch.org/vinci-company-profile/; Matt Broomfield, “Calais Jungle wall is completed two months after all the refugees were driven out,” The Independent, December 13, 2016, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/calais-jungle-refugee-camp-wall-completed-emptied-two-months-cleared-a7472101.html.

- 12Abigail Phillips, “Top 10 Construction Companies in the World,” Construction Global, January 3, 2015, https://www.constructionglobal.com/top-10/top-10-construction-companies-world.

- 13Water for All Campaign, “Veolia Environment: A Corporate Profile,” Public Citizen (February 2005), 1, https://www.citizen.org/sites/default/files/vivendi-usfilter.pdf.

- 14Veolia, “The history of Veolia: 1950–2000.”

- 15Veolia, “Our History,” https://web.archive.org/web/20120318162952/http://www.veolia.com/en/group/history/.

- 16Vivendi’s 1999 multibillion-dollar purchase of US Filter was the corporation’s most significant move into North American water privatization; at the time, it was the largest French acquisition of a US company in history. See Food and Water Watch, “Veolia Water North America: A Corporate Profile,” July 30, 2013, https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/insight/veolia-water-north-america-corporate-profile.

- 17“Prosecutors from the National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA), the country’s top law enforcement agency, said Bruno Roche, Apa Nova’s French CEO from 2008 to 2013, set up secret bank accounts and created fictitious contracts. These were then used to transfer millions of euros to senior Bucharest officials, who in return approved steep hikes in water bills,” Luke Dale-Harris, “French Water Executive Charged in Romania Corruption Probe: Romanian Corruption Fights Lands French Businessmen,” Politico, October 9, 2015, https://www.politico.eu/article/france-water-executive-charged-romania-corruption-probe/.

- 18Food and Water Watch, “Veolia Water North America: A Corporate Profile,” July 30, 2013, https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/insight/veolia-water-north-america-corporate-profile.

- 19Meera Karunananthan, “Blue Planet Projects Opposes Veolia in South Korea,” The Council of Canadians, April 15, 2015, https://canadians.org/blog/blue-planet-projects-opposes-veolia-south-korea.

- 20Veolia Environnement. “2012 Annual and Sustainability Report,” https://www.veolia.com/sites/g/files/dvc2491/files/imported-documents/2016/11/Veolia-annual-report-2012_0.pdf.

- 21“Under the British government’s support for the international mission led by the United Nations to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons, Veolia was chosen to destroy 150 metric tons of hazardous materials. The batches of ‘Class B precursor’ chemicals were treated at Veolia’s Ellesmere Port high temperature incinerator (HTi) in the United Kingdom, near Liverpool, under the existing hazardous waste treatment contract between Veolia and the Disposal Services Authority, a part of the UK Ministry of Defense,” from Veolia’s “2013 Annual and Sustainability Report,” 43, https://www.veolia.jp/sites/g/files/dvc891/f/assets/documents/2015/12/radd_veolia_2013_gb.pdf. Ironically, a company in breach of international law in its operations on occupied Palestinian land (discussed further later in this article) was awarded a contract to a UN body.

- 22Veolia, “2013 Annual and Sustainability Report.”

- 23Hydrocarbons Technology, “Carmon Creek Heavy Oil Project, Alberta,” https://www.hydrocarbons-technology.com/projects/carmon-creek-heavy-oil-project-alberta/.

- 24See Food and Water Watch, “Money Down the Drain: How Private Control of Water Wastes Public Resources,” 2009, http://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/reports/money-down-the-drain/; Food and Water Watch, “A Closer Look: Veolia Environnement,” 2010, http://documents.foodandwaterwatch.org/doc/veolia.pdf; Food and Water Watch, “Veolia Environnement: A Profile of the World’s Largest Water Service Corporation,” 2011, http://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/reports/veolia-environnement-a-profile/; Novato Friends of Locally Operated Wastewater, “Veolia and the Environment: A Bad Fit for Novato,” http://freepdfs.net/veolia-and-the-environment-a-bad-fit-for-novato-green-party-of/1eb2bff3a6f63a89ff50ad446c8cf5d0/.

- 25Food and Water Watch, “Veolia Water North America: A Corporate Profile.”

- 26Christina Lane, “City takes steps to end Veolia contract,” Longview News-Journal, September 4, 2012, https://www.news-journal.com/news/local/city-takes-steps-to-end-veolia-contract/article_a90825c7-c91d-5118-9c3d-19f2989a3a14.html.

- 27Sui-Lee Wee, “Chairman of Lanzhou Veolia Apologizes After Water Pollution in China,” Reuters, April 22, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-water-veolia/chairman-of-lanzhou-veolia-apologizes-after-water-pollution-in- china-idUSBREA3M07V20140423. For an additional public statement, see: "China: Chinese NGO Justice For All protests at Veolia Paris headquarter over benzene contamination in drinking water to 3.6 million people by Lanzhou Veolia," Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/china-chinese-ngo-justice-for-all-protests-at-veolia-paris-headquarter-over-benzene-contamination-in-drinking-water-to-36-million-people-by-lanzhou-veolia#c100758.

- 28Department of Attorney General, “Schuette Files Civil Suit Against Veolia and LAN for Role in Flint Water Poisoning,” https://www.michigan.gov/ag/0,4534,7-359-82917_78314-387198--,00.html; Sharon Lerner and Leana Hosea, “From Pittsburgh to Flint, the Dire Consequences of Giving Private Companies Responsibility for Ailing Public Water Systems,” The Intercept, May 20, 2018, https://theintercept.com/2018/05/20/pittsburgh-flint-veolia-privatization-public-water-systems-lead/. Public comment by Veolia in response to criticism has been minimal, but in a statement provided to BuzzFeed they asserted: "Veolia has consistently maintained that the crisis in Flint is a tragedy, and we find it disappointing that certain news organizations continue to recklessly portray the extent of the company’s work there." Monica Mark, "A Company at the Center of Flint Water Crisis is on the Shortlist to Serve Millions in Africa," BuzzFeed News, August 9, 2018, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/monicamark/lagos-flint-veolia.

- 29Veolia, “Integrated Utilities Management,” https://www.industries.veolia.com/en/activities/integrated-solutions/integrated-utilities-management-ium.

- 30Veolia, “Nuclear Solutions,” https://www.nuclearsolutions.veolia.com/en/about-us/nuclear-solutions. A part of Veolia’s consulting strategy, Seureca describes itself on its website: “Seureca is part of the Veolia Group, global leader in resource management. We provide expert solutions for utilities, public organizations, and industries to efficiently manage their water, waste, and energy services,” https://seureca.veolia.com/en/about-us/seureca/in-a-nutshell. Major water subsidiaries specializing in laboratory and maritime water treatment as well as drinking water, industrial wastewater, and sludge include, Elga, Sidem & Entropie, RWO, and OTV: “Veolia Water Technologies – Water and Wastewater Treatment,” https://www.veoliawatertechnologies.com/en/about-us/veolia-water-technologies. Part of Veolia’s Development, Innovation & Sales Division, 2EI targets city governments with promises of “sustainable solutions” and “anticipating and responding to environmental, economic and social crises” in the urban landscape using “public-private partnerships to innovate,” https://www.2ei.veolia.com/en.

- 31Veolia, “Our Locations Around the World,” https://www.veoliawatertechnologies.com/en/about-us/multi-local-presence.

- 32Chris Hedges, “Sweatshops on Wheels,” Truthdig, April 15, 2013, http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/sweatshops_on_wheels_20130415/.

- 33Transdev North America. “Why Contract with Transdev North America: The Leader in Public-Private Contracting in Transit,” http://www.transdevna.com/Company/Contract-Options/Why-Transdev.aspx.

- 34“Veolia’s Other Offenses,” Global Exchange, http://www.globalexchange.org/economicactivism/veolia/otheroffenses.

- 35Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. 2007.

- 36Benjamin Kabak, “NICE BUS, $7.3 million in the red, already threatening service cuts,” Second Avenue Gas, February 16, 2012, http://secondavenuesagas.com/2012/02/16/nice-bus-7-3-million-in-the-red-already-threatening-service-cuts/.

- 37Ironically, while Veolia took on a majority share of the paratransit contract in Seattle, the company was battling major debt and assuring its shareholders that it was getting out of the transportation sector entirely.

- 38Larry Lange. “Metro’s Union Files Labor Complaint,” The Seattle Post Intelligencer, August 12, 2008, https://www.seattlepi.com/local/transportation/article/Metro-s-union-files-labor-complaint-1282016.php.

- 39Transdev North America, “Veolia Transportation Awarded Seven Year Extension in Seattle,” Mass Transit, December 6, 2011, https://www.masstransitmag.com/home/press-release/10472864/transdev-north-america-veolia-transportation-awarded- seven-year-extension-in-seattle.

- 40https://transitriders.org/.

- 41At our height, SVS’s core was made up of a Metro bus driver and ATU member, two Access users, a seasoned water justice activist, an organizer in the early Black Lives Matter movement in Seattle, and members of the Northwest BDS Coalition including Students for Palestinian Equal Rights. Veolia drivers were never involved due to fear of retaliation. BAYAN, an alliance of progressive Filipino organizations, and the Transit Riders Union had written solidarity statements and were close collaborators. See Transit Riders Union statement of solidarity with Stop Veolia Seattle’s demand that King County terminate its contract with Veolia and restore jobs to union drivers: “In this age of austerity, working and poor people have been made to pay for the under-funding of public transit again and again...As bus riders, we understand the importance of standing up for the rights of our drivers...We will not stand by and watch as stable, family-supporting union jobs are replaced with poorly paid, precarious jobs,” and BAYAN Pacific Northwest’s solidarity statement: “We join Filipino Americans and allies globally in resisting Veolia’s attempts to profit from water and sanitation.” See Stop Veolia Seattle, “Solidarity Statements,” https://stopveoliaseattle.wordpress.com/solidarity-statements/.

- 42Marseilles Declaration for Palestinian Water Rights, April 10, 2012, http://www.fame2012.org/en/2012/04/10/declaration-palestine/.

- 43“Who Profits? Veolia’s Involvement in the Occupied Jordan Valley,” Jordan Valley Solidarity, November 2011, http://jordanvalleysolidarity.org/reports/who-profits-veolias-involvement-in-the-occupied-jordan-valley-an-update/.

- 44ATU Local 587 President highlighted the unions goal to “defend transit workers from predatory private contractors such as Veolia and First Transit.” Paul J. Bachtel, “The President’s Report” ATU Local 587 News Review XXXVII, no. 1 January 2014.

- 45Stop Veolia Seattle, “The Zine,” https://stopveoliaseattle.wordpress.com/the-zine/.

- 46“WHEREAS MLKCLC has made a commitment nationally to make common cause with struggles for social justice and workers’ rights around the world, building global solidarity to strengthen worker and union power everywhere; and WHEREAS MLKCLC knows that privatization undermines that effort and puts workers and users of public transport at risk,” https://stopveoliaseattle.wordpress.com/solidarity-statements/.

- 47Contract Change No. 3 was signed on July 19, 2010 included a reduction in minimal oil changes for the fleet and annual driver training from 24 to 12 hours.

- 48“Veolia/Transdev has Attempted to Divide our Coalition Because we call Attention to their Role in Israeli Apartheid,” Stop Veolia Seattle Zine Project (2012), 88, https://stopveoliaseattle.wordpress.com/the-zine/.

- 49In 2011, Veolia Environnement completed a deal with French state-owned bank, Caisse des Dépôts, merging their respective French-owned transportation subsidiaries to create a new French transnational transportation company that is jointly owned by the two. The new company is presently called Transdev and is 50% owned by the Veolia Group (until February 2015, Veolia Group was Veolia Environnement) and 50% owned by Caisse des Dépôts. In 2011, Veolia Transport ceased to exist in France, but the US subsidiary Veolia Transportation Services Inc continued to operate in the US until July 2014, when the US subsidiary changed its name to Transdev Services Inc. This name change reflects a definite change in ownership, as Veolia Transportation Services Inc was wholly owned by Veolia Environnement, while Transdev Services Inc is wholly owned by Transdev, which is only 50% owned by the Veolia Group. See “Veolia Transdev: Creation of the World’s Leading Private-sector Company in sustainable Mobility, Completion of the Merger of Veolia Transport and Transdev,” March 3, 2011, http://www.transdevplc.co.uk/cmsUploads/news/files/Veolia%20Transdev%20merger.pdf.

- 50In King County’s contract, Veolia Transportation Services, Inc., was identified as a “wholly owned subsidiary of Veolia Environnement,” Veolia Transportation never issued the county documentation that its parent company had changed.

- 51Stop Veolia Seattle, “King County Councilmembers Raise Concerns About Veolia’s Bad Practices, While Evidence that Veolia May Have Committed Fraud in King County is Surfacing,” https://stopveoliaseattle.wordpress.com/2015/03/27/king-county-councilmembers-raise-concerns-about-veolias-bad- practices-while-evidence-that-veolia-may-have-committed-fraud-in-king-county-is-surfacing/.

- 52Stop Veolia Seattle Zine Project (2012), 100.

- 53Ibid, 101.

- 54Paul Zilly, “New Transdev Contract will Transform Lives of 260 Teamsters and Their Families,” Teamsters Local 117, June 26, 2016, https://www.teamsters117.org/driving_toward_a_better_future_new_transdev_contract_transforms_lives.

- 55Jeff Switzer, “Metro Amends Future Access Paratransit Contract Requirements,” Metro Matters, June 12, 2018, https://kingcountymetro.blog/2018/06/12/metro-amends-future-access-paratransit-contract-requirements/.

- 56Jeff Switzer, “Metro Amends Future Access Paratransit Contract Requirements,” Metro Matters, June 12, 2018, https://kingcountymetro.blog/2018/06/12/metro-amends-future-access-paratransit-contract-requirements/.

- 57Sarah Rupp, “Metro Begins Negotiations with Top Proposer for new Access Contract,” Metro Matters, January 4, 2019, https://kingcountymetro.blog/2019/01/04/metro-begins-negotiations-with-top-proposer-for-new-access-contract/.

- 58Correspondence with Kergan Street. Transit Planner at King County Metro Transit, February 19, 2019.

- 59“Company Overview of MV Transportation, Inc,” Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/private/snapshot.asp?privcapId=4280701.

- 60“With Strike Looming, Union and MV Transportation Reach Tentative Agreement on New Contract,” Teamsters Local 727, September 28, 2018, http://teamsterslocal727.org/with-strike-looming-union-and-mv-transportation-reach- tentative-agreement-on-new-contract/.

- 61Anna Baltzer, “Veolia BDS Victories!,” US Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation, November 14, 2013, https://uscpr.org/archive/article.php-id=3737.html. Adri Nieuwhof, “Veolia Suffering ‘Expensive’ Damage Due to Palestine Campaigners’ Publicity, Says Financial Expert,” Electronic Intifada, February 19, 2013, https://electronicintifada.net/blogs/adri-nieuwhof/veolia-suffering-expensive-damage-due-palestine-campaigners-publicity-says.

- 62One Veolia official anonymously commented, "This has earned us boycott threats and lost us important contracts." "Jerusalem's long-awaited light rail finally ready to roll," RTE, November 22, 2010, https://www.rte.ie/news/special-reports/2010/1122/294690-israel/.

- 63Palestinian BDS National Committee, “BDS Marks Another Victory as Veolia Sells Off all Israeli Operations,” September 1, 2015, https://www.bdsmovement.net/news/bds-marks-another-victory-veolia-sells-all-israeli-operations.

- 64Patrick Bond, “Durban’s Water Wars,” 77.

- 65Veolia seems to have begun using these taglines heavily in their publications between 2014 and 2015.

- 66“Veolia Releases Annual Sustainability Performance Report,” May 24, 2018, https://www.veolianorthamerica.com/media/press-releases/veolia-releases-its-annual-sustainability-performance-report.

- 67“Factsheet: Protect Water: Boycott Nestle,” The Council of Canadians, January 2019, https://canadians.org/publications/factsheet-nestle.

- 68Ken Ward Jr., “Residents Wary of Antero’s Answer to Fracking Wastewater Problem,” Charleston Gazette-Mail, September 17, 2016, https://www.wvgazettemail.com/business/residents-wary-of-antero-s-answer-to-fracking-wastewater-problem/article_e159920f-51cb-5071-82fd-3eb1c522af96.html.

- 69“Veolia to Provide Utilities for DuPont’s Manufacturing Site in Virginia, USA,” Business Wire, April 18, 2018, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180418005792/en/Veolia-Provide-Utilities-DuPont%E2%80%99s-Manufacturing-Site-Virginia.

- 70Veolia, “The Essentials 2018,” https://www.veolia.com/sites/g/files/dvc2491/files/document/2019/04/Veolia-2018-The-Essentials.pdf.

- 71Veolia Chairman & CEO, Antoine Frérot summarized the strategic plan this way: “Our 2018 objectives are ambitious: Revenue should grow by more than €2 billion during the period, current net income should exceed €800 million and net free cash flow should nearly double to €1 billion. Confidence in our plan allows the Group to return to a dividend growth policy beginning this year, with the 2015 fiscal year dividend expected to be €0.73 per share, and annual dividend growth around 10% per year expected for the next three years.” Veolia, “Investor Day, Veolia reveals its new strategic plan for the 2016-2018 period,” https://www.veolia.com/en/veolia-group/media/news/investor-day-veolia-reveals-its-new-strategic-plan-2016-2018-period.

- 72Veolia, “Integrated Report 2018,” https://www.veolia.com/sites/g/files/dvc2491/files/document/2019/04/Veolia-Integrated-Report-2018.pdf.

- 73“About Our Water Campaign,” Corporate Accountability, https://www.corporateaccountability.org/water/about-water- campaign/.

- 74Bin Veolia Campaign, “Veolia Campaign Victories 2006-2012,” https://binveoliacampaignau.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/complete-rundown-bds-successes.pdf.

- 75“Veolia’s Other Offenses.”

- 76Ben McPartland, “Fired for Refusing to Cut Off Poor Families’ Water,” The Local: France’s News in English, April 19, 2013, http://www.thelocal.fr/20130419/sacked-for-refusing-to-cut-off-poor-families-water.

- 77Food and Water Watch, “Veolia Water North America.”

- 78Ibid.

- 79Moncton H₂0, https://monctonh2o.ca/.

- 80Patrick Bond, “Durban’s Water Wars,” 111.

Monica Mendoza

Map of Paris's sewers in 1878 (Crystal Bennes)

Compagnie Générale des Eaux drinking water plant in Neuilly sur Marne, France, ca. 1958 (Veolia)

Protests in Seattle over the privatization of accessible public transit Metro Access, 2008 (Maia Brown)

BDS logos targeting Veolia