Infrastructure in

America

Temporary Homes in Permanent Crisis

In September 2012, a class action settlement awarded $42.6 million to victims of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita who were living in mobile homes with elevated formaldehyde levels meted out as disaster assistance housing by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in partnership with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Following the hurricanes, over $50 million was spent on the production of more than fifty thousand travel trailers, with many of the contracts going to privately-owned companies that acted as middlemen for the homes’ procurement. The list of defendants named in the suit ran the gamut from architecture and engineering (A&E) conglomerates such as Shaw Environmental, Bechtel, Fluor, and CH2M Hill to medium-sized mobile home manufacturers and third-party procurement services like Vanguard, Forest River, Gulf Stream Coach, and North American Catastrophe Services.1 In the months following Hurricane Katrina, there was no time-sensitive plan to dismantle hazardous structures or finish home repairs for those affected by the hurricane. For years, as many as ninety-four thousand mobile homes with dangerous formaldehyde levels decayed in lots around the US South. These recognizable structures were broadly conflated with occupied mobile homes in New Orleans set up in front of houses too damaged to live in, and labeled as “blight” by the general public.2 In lieu of a resettlement program, fines were levied against those still living in the government-provided housing in order to force them out.3

The public uproar caused by the formaldehyde scandal, as well as the negative sentiment directed at the “Katrina trailers” that peppered the post-hurricane Gulf Coast landscape for years, caused a significant shift in the public perception of mobile homes as a viable disaster response strategy. This shift overshadowed their utility as ready-made housing that can be quickly transported to any area in the contiguous United States. In subsequent disasters, FEMA modified its emergency housing strategy to favor temporary rental housing, lodging expense reimbursement, and home repair or replacement over, in their official terminology, a “government housing unit.”4 In reality, mobile homes have still been widely utilized, most notably in response to Hurricane Harvey (and to a lesser degree, in response to the 2018 Camp Fire, 2020 Castle Fire, and 2020 Hurricanes Delta and Laura).5 In spite of these inconsistencies, what all the controversies swirling around government-provided mobile homes share is their connection to an increasingly privatized “temporary” housing system for which true accountability—for good design, for public health, and ultimately for the protection of lives and livelihoods—is unacceptably elusive, and for which crises too often become permanent.

Mobile homes sit in a field (Nick Shapiro)

Mobile homes sit in a field (Nick Shapiro)

In standard building construction there are typically multiple parties meant to operate in step with each other, ensuring that projects are built safely and efficiently. In this arrangement, all parties have firm legal responsibilities and a reliable framework for project execution. Considering that many of the companies contracted to source mobile homes after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita were effectively middlemen, it seems reasonable to assume that safety inspections—including monitoring the levels of formaldehyde gas emissions—would have been a component of their contracts.6 Though this assumption cannot be verified, damaging shortcomings of either the contract itself, or of its administration, are clear. That those mobile homes failed to meet basic safety standards on such a massive scale undermines beliefs about efficient and productive relationships between the federal government and private contractors, and calls into question whose interests the contractors were ultimately serving. More generally, this particular scandal highlighted the myriad other ways that mobile homes often fail to meet the needs of the people they are meant to help, including a lack of accessible spaces, a legally precarious homeownership status, and other potential safety failings. In “permanent” stick-built homes, these issues might typically be addressed by architects, building inspectors, lawmakers, and planners, but residents of manufactured homes oftentimes have no such dedicated third parties reliably acting in their interest.

Most mobile homes are prefabricated according to a finite set of designs, theoretically aligning them with the type of prefab or modular homes that have captivated architects since the beginning of the twentieth century.7 However, after the explosion of RV and travel trailer culture in the United States in the 1950s and 60s subsided, the idea of mobile homes as modern, affordable housing (or secondary homes) largely fell out of fashion. Mobile home manufacturing today is a streamlined process, concentrated in the hands of a few corporations collectively churning out tens of thousands of standardized units per year.8 Much of the innovation in mobile homes in recent years has come as a response to the historical stigma of “trailers”: larger models, better fire and structural safety standards, and aesthetic changes, such as a sparser use of aluminum siding, all manifest an effort to more closely resemble stick-built homes.9

The mobile homes that FEMA provides, in contrast, don’t conform to these trends. Emergency aid mobile homes are stripped down and often contain features that look like the more stigmatized “trailers” of the past, such as recognizable aluminum siding. Residents of disaster relief mobile homes are also prohibited from painting, rearranging, or otherwise personalizing their homes during their tenure.10 With an eye on the bottom line, “greener” models are generally bypassed when securing mobile homes for disaster victims.11 The negative environmental effect of FEMA models is compounded by situations like the one that played out after Katrina, with thousands left empty and rotting with no plan for their rehabilitation and reuse.

As a form of architecture, mobile homes are not inherently less functional or safe than stick-built homes—a fact made evident by the limited but persistent innovations in corners of the industry described above. However, socially entrenched ideas of mobile homes as fundamentally unsafe spaces have caused people to regard them as faulty or insecure, especially in the face of natural disasters. Each mobile home model is subject to rigorous wind and safety tests that make them as stable as most other small houses in a city undergoing an environmental crisis—especially considering that much of the damage incurred in high-wind disasters is from floating debris.12 Following the Mobile Home Safety and Standards Act of 1976, fires in mobile homes decreased by 75 percent, making them about as prone to fire hazards as single-family stick-built homes.13 Mobile homes can and should be subject to better regulatory enforcement throughout their life cycle, but their basic structural safety isn’t the issue at hand. As unique as the disaster scenarios are, if one can look past the individual scandals, what these conflagrations tend to foreground are actually endemic challenges for the industry and its constituents—challenges that are themselves rooted in this nation's structural inequity writ large.

In the United States, the notion of propertied citizenship is primary in civic life. Many Americans’ personal identities and financial power are tied to their home and the land on which it sits. FEMA has not wrestled much with the idea of what to do when mobile homes become permanent homes, staunchly maintaining separation between their responsibility—sourcing and disseminating disaster aid—and the realities of what happens to their “temporary” homes after families begin living in them.14 This disconnect between relief strategies as conceived and the lived experiences of affected populations on the ground often leaves citizens in legal and financial limbo. Few recipients of government-provided mobile homes have the opportunity to affordably purchase the home that they are living in, or to transition out of their provided mobile home to a vastly more expensive stick-built home. In Mobile Homes: The Unrecognized Revolution in American Housing, Professor Margaret Drury emphasizes this systemic problem by pointing out that “the foundation for government support and subsidy for housing has been based on ‘permanence.’”15

Even in mobile homes not distributed by the government, this ownership model is fraught with exploitation: mobile home owners tend to possess the home but not the land, which is rented out as a plot from a mobile home park owner.16 When residents of mobile homes are forced to move from their tract of land, the mobile homes often become more of a burden than a financial asset. Whether they are being sold by homeowners or by the federal government, the depreciation is extreme. Mobile homes have little to no resale value, robbing owners of the idealized expectation of the home as a family’s major economic investment. The cycle continues as owners of mobile homes, which have low value relative to stick-built homes as collateral for loans because of the lack of a connection to land ownership, find themselves targeted by predatory mortgages that can charge up to 10 percent in interest—a far cry from the 2–3 percent standard interest on mortgages for traditional stick-built homes. Despite all this, within private industry the average sale price for mobile homes is increasing while the average square footage is falling.17

Mobile homes sourced by FEMA would not typically be considered “accessible” under the building codes applied to stick-built construction. Given that a large number of mobile home residents (both during emergency scenarios and independent of them) are elderly, unable to work, or living with disabilities, this means that a significant number encounter obstacles in the basic use of their own home.18 All mobile homes, FEMA-procured and otherwise, are moved to their semi-permanent plot of land via public roads. Thus, all mobile and manufactured homes are built on a chassis thirty-six inches above the ground to lift the underbelly of the home during transport. Any resident with limited mobility requires subsequent, additional work, and additional resources, for their home to be made accessible. Often this takes the form of a bespoke wooden ramp, a costly feature that sociologist Esther Sullivan describes in Manufactured Insecurity: Mobile Home Parks and Americans’ Tenuous Right to Place as part of the mobile home vernacular.19

HUD guidelines for mobile homes detail basic layouts for mobile homes that are generally accessible, but which nevertheless have serious flaws. For one, these guidelines deal exclusively with making furniture and spaces accessible on the interior of the mobile homes, ignoring the aforementioned issue of accessible entryways. And once inside, though these mobile homes have a number of standard sizes and bedroom counts, the “standard” is not ideal for every type and size of family.20 When grouped together into a neighborhood of multiple mobile homes, there are relatively few legal requirements for mobile home park owners regarding common neighborhood facilities or infrastructure.21 Additionally, utility maintenance, trash pickup, and other duties are essential to the functioning of any residential area, and mobile home park residents have little recourse if the owner or operator of their park is neglectful about these services.22

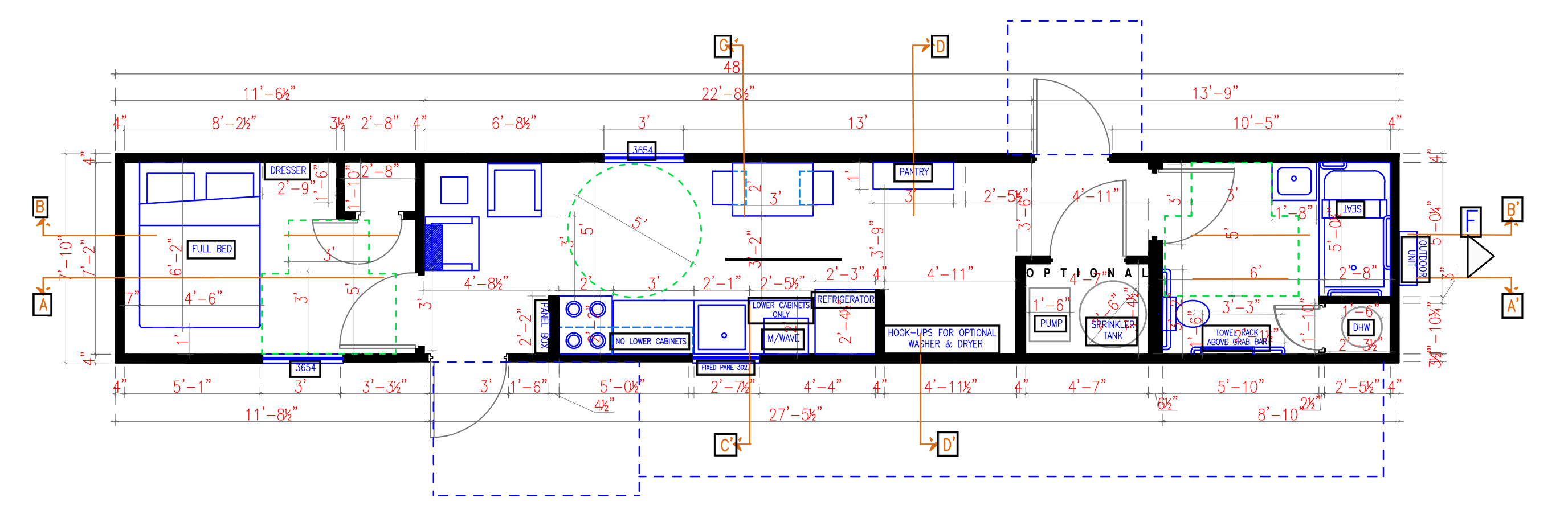

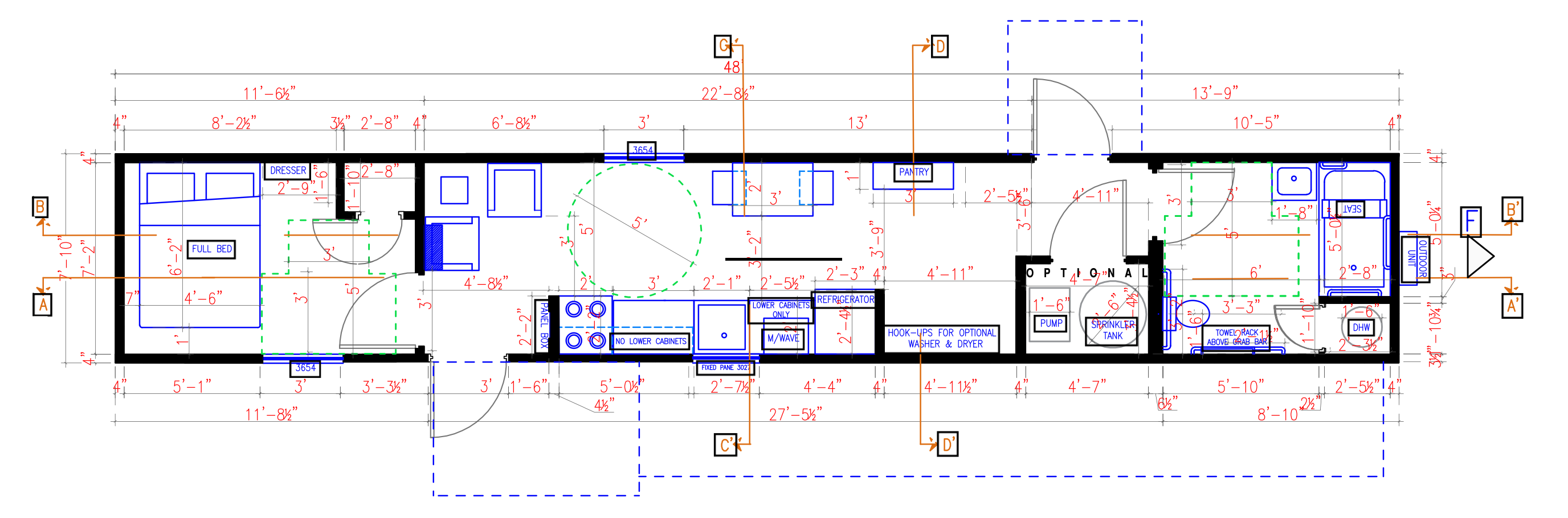

If the manufacturing and transportation of these structures can be standardized, there is no reason that the creation of structures to further facilitate accessibility couldn’t be included in the construction process. As they stand, construction standards are opaque, and often contradictory: HUD set rigorous guidelines in its 2003 Model Manufactured Home Installation Standards about overall structure (including foundations, ventilation, and electrical systems), but its current spatial standards are inadequate. For instance, corridor width is federally mandated to be at least twenty-eight inches wide, although broad consensus in architectural standards mandates thirty-two to thirty-six inches (for reference, a typical wheelchair is twenty-six inches wide).23 A 2016 conference organized by the Systems Building Research Alliance (SBRA) hosted key members of every major mobile home manufacturer in the US as well as a representative from FEMA in order to draft mobile home floor plans that were consistent with typical building standards. However, they chose to cite alternative codes such as the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA) and 24 CFR 3280, Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards (MHCSS) as opposed to the more rigorous ANSI 117 standards.24 Even then, while their interior floor plans were accessible, each plan mandated that accessible porches, ramps, and stairs be built onsite by others, but no guiding designs were provided for those features nor were the parties responsible for building them specified.25 These more accessible mobile homes have also not yet been standardized in the industry, and are distinct from the mobile homes currently being provided as disaster relief.

“Manufactured Housing Units, Federal Emergency Management Agency: Express Unit, Floor Plan” (Systems Building Research Alliance)

“Manufactured Housing Units, Federal Emergency Management Agency: Express Unit, Floor Plan” (Systems Building Research Alliance)

Comparable to the fungibility of other “sacrifice zones” and subject to the increasingly damaging effects of environmental injustice, mobile home parks are often demonized by city zoning boards trying to categorize the “highest and best uses” in their jurisdiction.26 People are forced to move as parks shutter and land is made available to programming that carries less social stigma. In these instances, mobile home residents’ self-made infrastructure cannot move with them, and they are often denied compensation for relocating these structures. In this way, temporary inconveniences become permanent problems.

Today, the mobile home industry operates largely out of view of the government and private organizations that typically deal with private housing. In addition to the countless instances of mobile home residents being displaced by changing zoning ordinances, neither architects nor contractors are typically involved in the making of individual mobile homes. This is true both in the factories, where it seems that architects are involved only rarely and exclusively at the level of early stage planning, and within the parks themselves, where owners tend to let maintenance issues and code violations continue unaddressed.27 Problems with mobile homes are difficult to fix, even when the federal government mandates it. Despite the fact that the government took action to recall each of the mobile homes with elevated formaldehyde levels after the problem was publicly identified on the Gulf Coast, and despite the fact that the government assumed the cost of replacing many of the hazardous homes, people were still found living in mobile homes marked “not suitable for housing” well afterward.28

By design, mobile homes can both be rapidly moved to the site of a disaster and safely house affected populations immediately, making them an ideal solution for short-term disaster relief. However, time and time again people in post-disaster landscapes have suffered from shortsighted recovery strategies that leave them in the lurch, depleted of financial resources, with few pathways back to stability, if they had it in the first place. Undue blame has been directed at the form of the mobile home itself. In fact, much more systemic challenges plague such uses, including FEMA’s lapses in management throughout the home’s life cycle, a dearth of long-term design and administration strategies, and the profit-oriented, largely unregulated culture of mobile home manufacturing and management. Of course, procuring thousands of mobile homes per day in the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster is exceptionally difficult, and it is no surprise that there were some errors in execution. But instead of allowing stigma to dictate a national strategy of withdrawal, there is potential to learn from the mistakes of the past and create a more robust management and quality assurance structure that would be applicable well beyond emergency scenarios.29 Many of the issues that arise from implementing mobile homes as disaster housing are a direct result of the fact that they reproduce a system already defined by decades of unaddressed predatory behavior, in which residents are excluded from the benefits and status of the kind of homeownership associated with stick-built homes. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Today, there is evidence that FEMA and HUD are aware of the promise of mobile homes in disaster scenarios beyond their use as a “last resort.”30 In 2020, tens of millions of dollars were awarded to mobile home companies for the housing of first responders to Hurricane Laura.31 The clear difference in this scenario is that responders likely have primary homes to which they can return, relieving federal and state agencies of the responsibility to oversee their transition out of temporary lodging. In approaching mobile homes as disaster relief housing today, it is clear that many of the persistent challenges stem from a lack of rigorous regulation of private manufacturers. These issues are patched with vague assurances from private industry to do better, combined with a restriction on public-facing dialogue about the merits of mobile homes as temporary housing. But core policies must change, otherwise the nation risks continuing to reproduce injustice in its national disaster relief strategy, and inflicting a state of permanent disaster upon many people who have no way out.

- 1“Katrina, Rita Victims Get $42.6M in Toxic FEMA Trailer Suit,” CBS News, September 29, 2012, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/katrina-rita-victims-get-426m-in-toxic-fema-trailer-suit/.

- 2Pam Flessler, “Trailer Graveyards Haunt FEMA, Neighbors,” NPR, July 8, 2008, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=92183909.

- 3Cain Burdeau, “New Orleans Getting Rid of Last FEMA Trailers,” NBC News, December 31, 2010, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna40858571.

- 4“Assistance for Housing and Other Needs,” FEMA, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.fema.gov/assistance/individual/housing.

- 5Current and former representatives of FEMA continuously refer to the usage of trailers as a “last resort” despite FEMA’s continuing contracts with RV and trailer suppliers (as of 2019). See “Blanket Purchase Agreement (BPA), PIID HSFE0417J0097,” USAspending, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.usaspending.gov/award/CONT_AWD_HSFE0417J0097_7022_HSFE0417A0026_7022; “Purchase Order (PO), PIID 70FA3020P00000038,” USAspending, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.usaspending.gov/award/CONT_AWD_70FA3020P00000038_7022_-NONE-_-NONE-; “Purchase Order (PO), PIID 129AB520K6094,” USAspending, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.usaspending.gov/award/CONT_AWD_129AB520K6094_12C2_-NONE-_-NONE-; “Purchase Order (PO), PIID 70FB7018P00000021,” USAspending, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.usaspending.gov/award/CONT_AWD_70FB7018P00000021_7022_-NONE-_-NONE-.

- 6Daniel Friedman, “Formaldehyde Gas & Outgassing Hazards In Buildings,” InspectAPedia, accessed December 10, 2020, https://inspectapedia.com/indoor_air_quality/Formaldehyde_Gas_Sources.php.

- 7Barry Bergdoll and Peter Christensen, Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling (Basel: Birkhäuser; New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2008).

- 8Sarah Baird, “Mobile Homeland,” Curbed, September 13, 2017, https://archive.curbed.com/2017/9/13/16275948/mobile-manufactured-homes-clayton-trailers; Christian Cavallo, “Top Mobile Home Manufacturers in the US,” Thomas, accessed December 15, 2020, https://www.thomasnet.com/articles/top-suppliers/mobile-home-manufacturers-suppliers/.

- 9Here, trailers are defined as manufactured homes built before the 1976 establishment of federal construction and safety standards for mobile homes by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

- 10Stephen Verderber, “Emergency Housing in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: An Assessment of the FEMA Travel Trailer Program,” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 23, no. 4 (2008): 367–81, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-008-9124-y.

- 11Systems Building Research Alliance, “Subject Matter Expert Panel Meeting,” November 18, 2015, accessed December 12, 2020, http://www.research-alliance.org/pages/fema/Panel%20Meeting%20Minutes_1.pdf.

- 12“Understanding and Improving Performance of New Manufactured Homes During High-Wind Events,” FEMA DR 1679 RA5, February 2007, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1604-20490-9562/ra5_new_manuf_homes.pdf.

- 13John R. Hall, Jr., Manufactured Home Fires (Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association, September 2013), accessed December 15, 2020, https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Data-research-and-tools/Building-and-Life-Safety/Manufactured-Home-Fires; Baird, “Mobile Homeland.”

- 14HUD’s setting of mobile home standards while FEMA oversees disaster response could foment contractual slippages between the two agencies with regard to this issue.

- 15Margaret J. Drury, Mobile Homes: The Unrecognized Revolution in American Housing, rev. ed. (New York: Praeger, 1972), 131.

- 16“Manufactured Housing and Standards - Frequently Asked Questions,” HUD, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/housing/rmra/mhs/faqs.

- 17Baird, “Mobile Homeland.”

- 18Baird, “Mobile Homeland”; Robert W. Wilden, Manufactured Housing and Its Impact on Seniors (Washington, DC: Commission on Affordable Housing and Health Facility Needs for Seniors in the 21st Century, February 2002), https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/seniorscommission/pages/final_report/manufHouse.html.

- 19Esther Sullivan, Manufactured Insecurity: Mobile Home Parks and Americans' Tenuous Right to Place (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2018).

- 20“Manufactured Homes,” in Protecting Manufactured Homes from Floods and Other Hazards: A Multi-Hazard Foundation and Installation Guide, FEMA P-85, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: Federal Emergency Management Agency, November 2009), 1–10, https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1501-20490-6842/fema_p85_ch2.pdf.

- 21Baird, “Mobile Homeland.”

- 22Many lawsuits have been brought and won against extremely neglectful park owners, but these lawsuits are expensive and tend to leave residents living in substandard conditions for years. Tracey Kaplan, “Mobile home park victory: A negligent owner, $10 million settlement and the San Jose residents who prevailed,” East Bay Times, March 6, 2017, https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2017/03/05/4434205/.

- 23The “24 CFR Part 3280 Manufactured Home and Construction Standards” mandated by HUD are looser than typical standards (American National Standards Institute [ANSI 117.1]), and sometimes contradict other standards used within the mobile home industry, including the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA), and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

- 24“Universal Floor Plan Design for FEMA Disaster-Relief Housing,” Systems Building Research Alliance, accessed December 13, 2020, http://www.research-alliance.org/pages/fema_mhu.htm.

- 25“Manufactured Housing Units, Federal Emergency Management Agency: Express Unit, Floor Plan,” Systems Building Research Alliance, revised November 10, 2016, accessed December 12, 2020, http://www.research-alliance.org/pages/fema/express_sme.pdf.

- 26Steve Lerner, Sacrifice Zones: The Front Lines of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010).

- 27Linwood Rogers, “A Framework for Forming Resident-Controlled Manufactured Housing Communities in Richmond” (master's thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2020), https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1031&context=murp_capstone.

- 28Heather Smith, “People Are Still Living in FEMA's Toxic Katrina Trailers—and They Likely Have No Idea,” Grist, August 27, 2017, https://grist.org/politics/people-are-still-living-in-femas-toxic-katrina-trailers-and-they-likely-have-no-idea/.

- 29“Assistance for Housing and Other Needs.”

- 30“Assistance for Housing and Other Needs”; Mike Brunker, “CDC tests confirm FEMA trailers are toxic,” NBC News, February 14, 2008, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna23168160; Michael Kunzelman and Michael Biesecker, “FEMA Isn't Relying on Trailers to House Hurricane Victims,” AP News, September 19, 2017, https://apnews.com/article/2fee1ed3e6e2400bb906048133d94ddf; Emily Schmall and Frank Bajak, “FEMA sees trailers only as last resort after Harvey, Irma,” ABC News, September 10, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20170914220012/http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/fema-sees-trailers-resort-harvey-irma-49742355; Kimberly Kindy and Aaron C. Davis, “With thousands still in shelters, FEMA's caution about temporary housing hinders hurricane recovery,” The Washington Post, October 28, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/with-thousands-still-in-shelters-femas-caution-about-temporary-housing-hinders-hurricane-recovery/2017/10/28/58bd2ae0-acdf-11e7-be94-fabb0f1e9ffb_story.html.

- 31“Definitive Contract, PIID 70FBR420C00000004,” USAspending, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.usaspending.gov/award/CONT_AWD_70FBR420C00000004_7022_-NONE-_-NONE-; “Purchase Order, PIID 70FA3020P00000038,” USAspending, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.usaspending.gov/award/CONT_AWD_70FA3020P00000038_7022_-NONE-_-NONE-.

FEMA trailers at an auction in Hammond, Louisiana (Nick Shapiro)

(Nick Shapiro)

“Manufactured Housing Units, Federal Emergency Management Agency: Express Unit, Floor Plan” (Systems Building Research Alliance)