Infrastructure in

America

The Professionalization of Care: Health

Amidst a global pandemic, the notion that “healthcare is a human right” has been increasingly centered in political discourse and debate within and without the borders of the United States. And health is not alone; rather it is often discussed along with other systems of care—such as education, housing, social security, etc.—not only in terms of policy, but also using a language of human, or universal, rights.

The profession of architecture, in contrast, most conventionally links the concept of health with codes and regulations. Health is typically not coined “healthcare” but rather “health and safety,” and is conceived according to material guidelines. As they inform the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and other building codes, these notions of health and safety are oriented toward two discrete—and discretely professional—phases and audiences: construction/constructors and occupancy/occupants.

But before the professionalization of architecture comes education, and schools of the built environment are established to both understand and engender built work in the world—with all the contradictions and tensions that implies, not least in the realm of health. What happens when such seemingly disjointed vocabularies of health are laced together inside the academy? Although the most seemingly straightforward and therefore expected combination of health and design is programs that prepare students to design and build healthcare facilities, the reality is much more varied.

The American Institute of Architect’s (AIA) and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture’s (ACSA) Design & Health Research Consortium is one entity poised to help us better understand the complex status of these intersecting discursive, pedagogical, and material systems. Consisting of nineteen member institutions, the Consortium works with each school to find funding and platforms that enable them to translate “research that connects design decisions with health outcomes.” Most critically, the Consortium points toward the oft-invoked dilemma of theory versus practice, specifically revolving around the outlets of research.

Members of the Design & Health Research Consortium are expected to:

- strengthen the design and health knowledge base by documenting and disseminating peer-reviewed research

- develop evidence-based tools for practicing professionals informed by current research

- translate the outcomes of research for policymakers and the general public1

When designing and planning in ways that seek to improve the general health of people, systems, and environments, where is the confluence between research and practice? How does the professionalization of health manifest when it circumvents explicitly addressing the design of health facilities?

Of the nineteen members, the triangulation of the following three institutions foregrounds distinct goals, methods, and outcomes that, in conversation, begin to respond, at least in part, to these and other questions. Kent State University’s Master of Healthcare Design, the University of Minnesota’s “design and health” projects at the Minnesota Design Center, and the University of Arizona’s M.S. in Architecture in Health and Built Environment as well as their Institute on Place and Wellbeing offer those interested in design and health interesting similarities as well as differences. All public schools with comparable student population sizes, they underline certain common educational structures between degrees and institutes. On its website, Kent State presents itself as a more traditional combination of health and architecture, equipping students to design healthcare facilities, while the latter two institutions offer less expected combinations of health and design.2 In addition to the questions regarding professionalization listed above, all three also ask, perhaps more fundamentally: What is the unit of care being taught? Is it the building? The system? The body? The community? The city? Where is health being discussed in the realms of design and planning—and where isn’t it?

One might expect Kent State University’s Master of Healthcare Design degree to represent the norm of when health and design intersect. As the program advertises on its homepage, there is a direct linkage that treats healthcare facilities as the built environment to be designed—hospitals, clinics, and “other environments of care.”3 Notably, this degree is meant to be obtained post-professionally, intended for those who have already earned an accredited architecture or interior design degree, yet it is also open to professionals with a wide array of backgrounds. The Master of Healthcare Design, also known as MHD, posits a learning outcome that is in direct alignment with—if not purposefully alluding to—the Design & Health Research Consortium’s key mission of disseminating research: “understand and translate research literature into real-world design practice.”4 That being the first outcome listed out of three, the latter two begin to suggest a rather broad scope, with the first addressing safety, quality, and efficiency and the second accounting for learning more about the specific purposes and populations within healthcare environments.

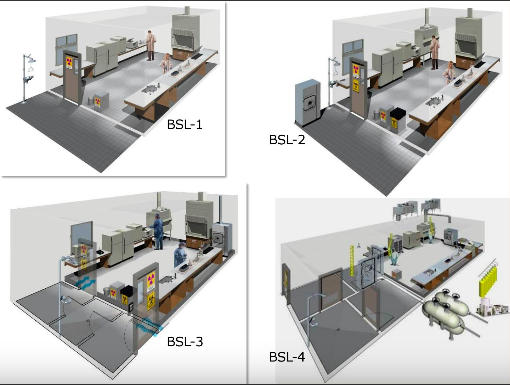

Digging further into MHD’s curriculum unveils the web of disciplines, sequences, and resources that seek to bridge the gap between research and practice. Like most architecture programs, the MHD curriculum is sorted into a core curriculum with supplementary electives. However, unlike most architecture programs, MHD’s core courses are not contained to the studio, and electives are vastly interdisciplinary. The core curriculum—consisting of classes including a healthcare design studio, “Practical Experience” (research or internship), systems and design workshops (including one on culture and ethics), “Evidence-Based Design,” “Healthcare Facilities,” and “Patient Safety and Systems Thinking”—takes into account both the tangible and intangible, the professional as well as the conceptual. Yet interestingly, although MHD can be considered one of the more design-heavy programs within the Consortium, only one of its nine core courses is a studio, and two others are considered as workshops. Among the rest of the core courses, including a practicum and five lectures, there is notably a variety in the way lectures are taught, ranging from an emphasis in teaching an evidence-based design process to surveying the design finishes and mechanical systems that go into healthcare facilities.

While the core sequence is contained in the department of Healthcare Design (HCD) within the College of Architecture and Environmental Design, the elective courses link students up with the Colleges of Public Health and Nursing, and departments including Environmental Health and Safety, Health Policy and Management, and Social and Behavioral Sciences. If the core curriculum is meant to do most of the work of bridging research and practice, then the elective offerings are empowered to go beyond the discrete intersection of health and design; for example, many of the elective courses provide more in depth looks at healthcare facilities, such as Laboratory Safety and Hygiene. Courses like Obamacare and National Health Reform and Developing Environments for Older Adults show that although this degree appears to be the most conventional and straightforward, students can draw the boundaries for themselves between health and design in creative ways with these electives.

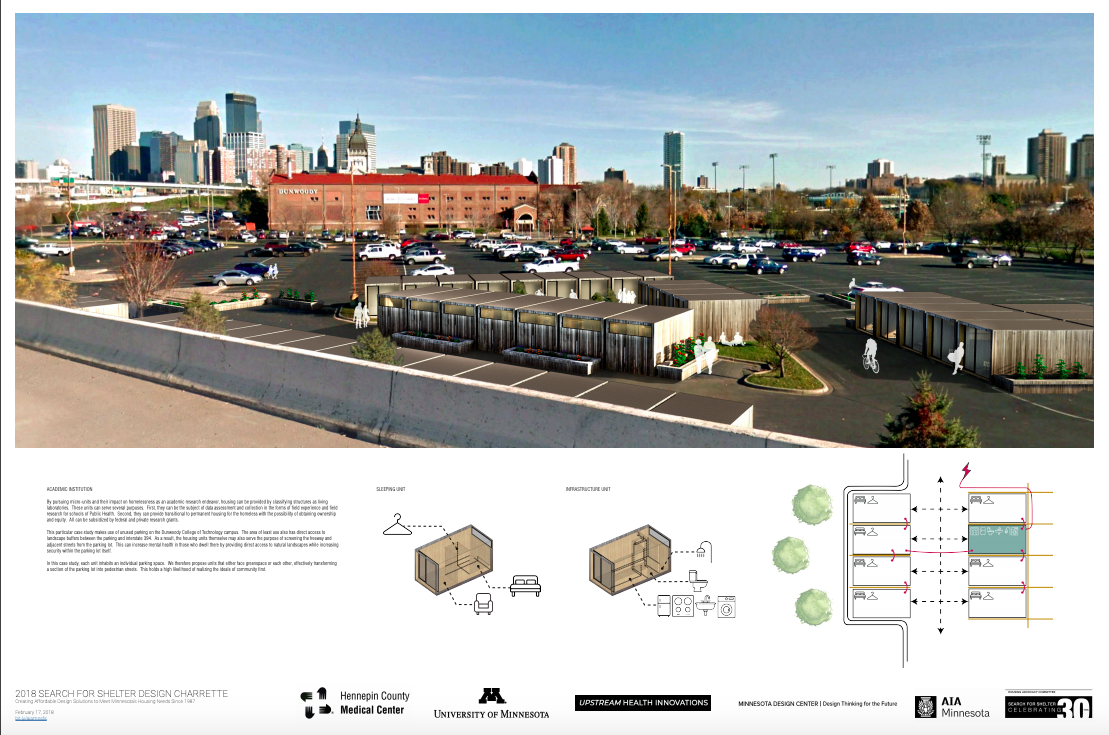

While the University of Minnesota does not have any degrees or concentrations focused on health, the Minnesota Design Center within the College of Design has a robust set of projects labeled under “Design & Health.”5 The Center is featured as a member of the AIA ACSA Consortium for their “health-focused, human-centered” collaborative processes between designers, architects, students, and public health experts that engage in “in situ” research together with underserved communities.6 Based on their publicly available material, the unit of care and health this center seeks to work with is that of the community. This complicates the locating of this center’s juncture between research and practice.

Some of their projects focused on the community begin to illustrate a way of thinking about health that goes beyond discrete systems of the body or building. The center’s project “Design for Community Regeneration (D4CR),” for example, seeks to partner with regional rural and urban clusters of communities in a process that “imagin[es] and plan[s] their resilient future addressing food, water, and energy security while increasing economic opportunities, social cohesion, and finding low cost housing options.”7 This expansion of health’s boundaries follows an expansion of scale; as access and proximity to resources is considered alongside the wellbeing of individuals, it inevitably involves the larger systems.

What also makes the communal scale a noteworthy bridge between research and practice is the foregrounding of participatory planning. In working with local communities, D4CR seeks to foster an inclusive decision process that features a “ground-up ‘Geodesign’ process” as well as a dashboard explicitly displaying community goals.8 Discourse surrounding community participation naturally involves questions about the benefits and constraints of partnerships. The Center features several projects in collaboration with outside entities, including the project “Health = Housing” alongside Hennepin County Medical Center’s Upstream Health Innovations and “Design Thinking for Leadership at the Centers for Disease Control” with Allina Health. How might the assertion of healthcare as a human right translate from architects through such different stakeholders and back again?

The University of Arizona offers both an institute and degree involving health, between the M.S. Architecture in Health and Built Environment and the Institute on Place and Wellbeing. On the degree’s homepage, language akin to Kent State and the Consortium is featured, attesting that “designers who can not only understand, but translate existing research into practice will be more competitive in the market and have a positive impact on the everyday lives of people.”9 While they go on to further fortify the Consortium’s goal—equipping architecture students to be able to critique existing scientific research, translate findings into design, and introduce new human health design standards—what is also apparent in the case of the University of Arizona is the professional instrumentality of language associated with such specializations. Notions that these skills add a competitive edge for students in the market parallel similar expressions of efficiency and effectiveness within their adjacent institute. The Institute on Place and Wellbeing (IPW) is a joint effort between the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine, the College of Medicine, and the College of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape Architecture. In their mission statement, these notions of efficiency and effectiveness go beyond the pedagogies and skills taught, and extend to their overall research and definitions of health. For the IPW, health is not only conceived in tandem with wellbeing, creativity, and productivity—specifically in work environments—it is a quality meant to be maximized by occupants. Health and wellbeing can be discreetly tracked by “state-of-the-art technologies such as non-invasive micro-devices and analytic algorithms.”10 While the teaching and utilization of data collection, coupled with partnerships from the architecture school that encourage developing new design standards, appears to pinpoint the Consortium’s mission most comprehensively, it seems to leave health itself in a rather unconventional, if not ambiguous, standing. Whereas in earlier instances health appeared to be a marker of the division between research and practice, it here appears to be the actual means of bridging the gap.

The integration of health into the world of design pedagogy highlights inherent tensions not only between research and practice, but also between politics and professionalization. The format of courses and the disciplines in which they are anchored can better allow research to be digested and projected into design decisions, just as they can complicate smooth instrumentalization; the unit of health when studied can bring forth partnerships that expand the range of voices informing what is studied and why, just as it can impose complicating and at times contradictory demands; and the institutional development of individual expertise can inform new and necessary future innovations, just as it can draw resources away from what might be considered a ‘core’ competency elsewhere.

If healthcare is a human right, what should design professionals be able to say about it?

- 1“Design & Health Research Consortium,” The American Institute of Architects, https://www.aia.org/resources/78646-design--health-research-consortium.

- 2With access to each program’s curricula and institute information constrained to respective websites, it is critical to qualify that information can range significantly in detail and granularity based on the resources put into a website. These three schools all maintain comparable levels of details on their websites, including course information, curricular sequences, and faculty directories. “Master of Healthcare Design,” Kent State University, https://www.kent.edu/caed/master-healthcare-design.

- 3“Master of Healthcare Design.”

- 4“Master of Healthcare Design.”

- 5"Projects,” Minnesota Design Center (University of Minnesota College of Design), https://designcenter.umn.edu/projects/.

- 6“Design & Health Research Consortium.”

- 7Tim Griffin, Dewey Thorbeck, and Jonee Brigham, “Design for Community Regeneration (D4CR),” Minnesota Design Center, https://designcenter.umn.edu/.

- 8It is not clear however what “community”consistently entails. Is this a governing or representative body? How do these community members come into these bodies, and how are such bodies selected by the Center to work with? Such questions are integral to keep in mind. Griffin, Thorbeck, and Brigham, “Design for Community Regeneration (D4CR).”

- 9“MS. Arch in Health and Built Environment,” Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine, https://ipwp.arizona.edu/MSArchDegree.html.

- 10“MS. Arch in Health and Built Environment”

Kent State University's Master of Healthcare Design, CAED Infectious Contagions Seminar Powerpoint

University of Arizona's Institute on Place, Wellbeing & Performance, Rooms for Wellbeing

University of Minnesota's Minnesota Design Center, 2018 Search for Shelter Design Charrette