Infrastructure in

America

Working with the Commons

In Cochabamba, the third largest city in Bolivia, water and its scarcity are at the center of daily life. Water is both a productive source of health and a strong indicator of power in Bolivian society. As a material, cultural, and symbolic reference point, it has also become a tangible focus for electoral promises and political manipulations.

Therefore, water is also a topic of public concern. It looms large for individuals on their own and those acting collectively in associations, neighborhoods, and communities alike. In the countryside around Cochabamba, families generally depend upon agriculture, and as one of the long-foundational inputs for labor, the distribution, access, and management of water is carefully organized in complex ancestral systems. But inside the city and within its suburban peripheries, where migration during the late 1980s led to accelerated and disorganized growth, authorities have failed to organize a centralized solution. Urban access to water has therefore led to a multiplicity of individual and collective actions, some of which are community-based, while others are of a commercial nature. This is the environment in which the Bolivian government launched a major privatization program at the end of the 1990s that has culminated in what is known as the Cochabamba Water War.

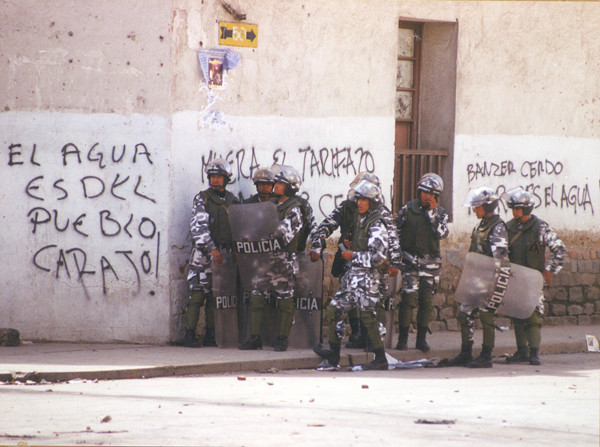

Graffiti reading "The water is the people's, damnit!" next to a group of Dalmatas, special forces brought in by the government to suppress demonstrations, February 2000 (Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida)

The Water War

Beginning in the mid-1980s, structural adjustment programs dominated economic and political policies throughout South America. Pushed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 1985 the Bolivian government issued DS21060, a presidential decree enacting a series of policies that decimated social services and paved the road to privatize public institutions. These privatizations were not simple transfers of ownership from state to private hands, but were accompanied by structural adjustments aimed at facilitating and encouraging foreign investment.

In 1999, as a continuation of the same policies, the Bolivian government privatized the water supply to the city of Cochabamba with the passage of Law 2029, which eliminated any guarantee of water distribution to rural areas and allowed foreign companies to lease an exclusive access to water.1 Up until then, irrigating farmers, communities, and neighborhoods on the periphery of the city had built and were reliant on autonomous water services.2 That is, they were not connected to the municipal water system. But with the passage of Law 2029, they lost their rights to manage their own water sources and were forced to rely on public infrastructure. With this legal provision in place, the public water utility, Servicio Municipal de Agua Potable y Alcantarillado (SEMAPA), was incorporated into the consortium Aguas del Tunari, whose majority shareholder was the multinational corporation Bechtel.3 SEMAPA thus relinquished its right to manage the region’s water supply. As Law 2029 placed autonomous water systems in the position of administering water service without a state concession, they could be sued by Aguas del Tunari for unlawful competition and have their existing, community-owned systems taken from them and made to serve the company’s needs. Meanwhile, in the city, people faced exorbitant increases to their water rates, with some bills increasing by 200%.4

This scenario gave birth to the Coalition for the Defense of Water and Life (Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida), a platform that brought together factory workers, campesinos, neighborhood associations, academics, and individuals without a defined organization. The Coordinadora allowed people in both urban and rural areas to mobilize with a degree of unity that had been absent for close to twenty years.5 Thousands of people responded to its initial call for mobilization on January 11, 2000. The government greeted them with tear gas.

Four days later, an agreement between the protestors and the government was signed, in which the government committed to review Law 2029 and its contract with Aguas del Tunari.6 But the government refused to lower water rates. People then began refusing to pay their water bills, and in February, the Coordinadora realized that the agreement to review both the law and the contract was not being honored. In response, it called for a peaceful and symbolic seizure of the city’s central plaza, demonstrating the unity and legitimacy of the people’s demands to pressure the government to act. The government banned the protest and brought in police from other parts of the country to help repress the demonstrators. Over the next two days, central Cochabamba became a war zone, where more than a hundred protesters were injured. An agreement was reached forty-eight hours later that froze the city’s water rates at November 1999 levels and forced the government to form a commission to review the articles of the law and the terms and conditions of the contract.

Popular mobilizations achieved significant gains that month. People won respect for their traditional water management methods; indexing water prices to the dollar was eliminated; municipal participation in water management was mandated; and the state formally recognized the legal existence of autonomous community water systems. All this had been won through protest and mobilization. These were important victories, but the contract with Aguas del Tunari remained intact.

Protest on San Martín, one of the main streets in Cochabamba, April 2000 (Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida)

As a result, a process of popular consultation and a series of assemblies were organized to formulate specific demands. More than 50,000 people participated. When these demands, which included breaking the contract with Aguas del Tunari, were not recognized by the authorities, people responded by forming street blockades.7 Over the following days, the number of people in the streets grew larger and the blockades became more widespread. Despite allegations that they had decided to break the contract, a few hours later, the government announced that the contract would not be broken and declared a state of emergency.8

Soldiers occupied the streets. Violence worsened. The spokespeople of the Coordinadora were targeted and harassed. A seventeen-year-old was shot and killed by the military. The people raised their demands, calling for the company and the President of the country, Hugo Banzer Suarez, to leave, and for a popular constitutional assembly to be formed.9 Finally, after days of confrontations, the company was expelled. For Bolivia, this was the first popular victory in almost two decades of neoliberal rule under structural readjustment programs. It changed history.

The Cochabamba Water War marked the starting point of a wave of water struggles in Latin America. It has played an important role in inspiring water movements and organizations to collaborate on a global scale, and has helped impede the momentum of water privatization efforts around the world. It also served to motivate the electorate in several Latin American countries to move toward more progressive and democratic governments. However, at the same time, it has shown how difficult the resulting challenges for the public management of water are.

Distributing and rationing potable water in Cochabamba, 2016 (El Diario Nacional de Bolivia)

Nineteen years later

From the perspective of the state, the 2000 Cochabamba Water War is described as a citizen-led struggle in which people took to the streets to demand the application of the human right to water. But this is not how it felt on the ground.

The organizational base that mobilized against the privatization of water and the commodification of its supply consisted of a variety of community and neighborhood associations that, before Bechtel’s arrival, built and maintained the systems that provided both irrigation in rural and provincial areas and drinking water in the city. There was great diversity to these collectives, but one commonality among them was that they all, to greater or lesser extents, employed collective decision-making processes to determine the access, management, and availability of water. They decided on the services provided; the design standards of the distribution systems used; and their own organizational, structural, and managerial forms. They developed their own methods for resolving conflicts, usually under a framework known as usos y costumbres (uses and customs).10 These organizations made decisions with and within their communities. They were not reliant on the state.

It was only in 2010 that the United Nations General Assembly explicitly recognized the human right to water and sanitation and acknowledged that clean drinking water and sanitation are essential to the realization of all human rights.11 At that time, it called upon states and international organizations to provide financial resources and to help with capacity-building and technology transfer in order to assist countries in providing safe, clean, accessible, and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all.

Also in 2010, the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth was held in Cochabamba, where a Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth was formulated, and later incorporated into the Bolivian state as Law 071. The Law of the Rights of Mother Earth defines Mother Earth as “a collective subject of public interest.”12

As positive as these two initiatives might appear, they are both currently being used by the Bolivian government to yet again take away people’s authority to manage their own water. In several public interventions and writings, both Evo Morales and Alvaro Garcia, the country’s president and vice-president, have declared that the capacity to satisfy the needs of the people must be assumed by the state. Disregarding the history of autonomous water management, those seeking access to water must now appeal to the state, the legislature, and the courts.13

Andean cosmologies largely consider water as both a living being and a divine being. Water in the Andes is the basis of reciprocity and complementarity; it helps to resolve problems and to establish relationships. Water is everyone’s and no one’s. It is the element that helps nature create, transform life, and permit social reproduction. The current Bolivian government under Evo Morales is attempting to undermine this fundamental relationship between people and water by paternalistically co-opting, controlling, and unifying water systems.

Prior to privatization in 2000, water in Cochabamba was provided by a variety of means. SEMAPA, the municipal water company, was the biggest and most visible supplier, but there were many others: there were rivers, wells, and rain catchment systems, as well as private delivery trucks. Many neighborhoods and communities accessed their water from a variety of these sources. There was, in short, a complex system of water delivery, and it served communities well. Some neighborhoods pooled their money together to construct a system that delivered water directly to their houses and would collectively pay for maintenance and electricity bills. Others accessed it through water houses, cisterns, or delivery by truck. Decision-making about water access was part of constructing the commons.

The current Bolivian government, which came to power on the rhetorical platform of giving people the ability to decide, has in fact weakened the exercise of autonomous power in expanded areas of influence.14 New legislation and bureaucracy has given power to the state in areas that have traditionally fallen outside of its scope.15 It claims that the problems the country has faced in the past decades, including those surrounding water access and management, have been due to mismanagement by the state. But, the logic continues, now that the state has been redefined and reconstituted, it is no longer necessary to address social concerns at the community level.16 Since then, according to the government, mobilizations have solely been concerned with complaining about the poor distribution of state funds. From this limited point of view, the collective only organizes itself to demand things from the state.

In general, an important strength of autonomous water communities is their ability to collaborate with public water systems.17 These communities do not compete with public networks, but rather decide how and to what extent to connect to them. The state promotes its projects as public assets, but citizens should question if something is really public just because it belongs to the state, particularly when it precludes autonomous decision-making practices for local communities and environments. The Cochabamba Water War was a victory against privatization, but it was not simply a struggle to restore SEMAPA as the public water utility.18 It was a struggle to expand participation in determining the conditions of people’s lives. This struggle lives on today.

- 1Oscar Olivera and Tom Lewis, Cochabamba: Water War in Bolivia (Cambridge: South End Press, 2004), 7-8.

- 2A legal loophole allowed these water systems to function without any permission from the state. However, autonomy is also a tradition in Bolivia. Since the creation of the republic, the state has been largely absent, especially in non-urban areas. This has made possible the creation of autonomous initiatives with practically no regulation. Since Evo Morales came to power, the state has initiated a process of expanding into areas previously left alone—not necessarily to provide services but to regulate and profit from them.

- 3Bechtel’s 2001 income was $14.3 billion dollars, while Bolivia’s GDP that same year was $8.1 billion dollars. By the time the contract was signed, Aguas del Tunari was a consortium whose majority (50%) shareholder was International Water Holding B.V., a subsidiary of Bechtel. The Spanish multinational corporation Abengoa Servicios Urbanos held 25% of the shares, and four Bolivian companies held the remaining shares.

- 4Jim Shultz, “Bolivia’s War over Water,” Democracy Center (2003), https://democracyctr.org/archive/the-water-revolt/bolivias-war-over-water-book-chapter/.

- 5Until the 1980s, unions (mainly miners) were the primary mobilizing force in Bolivia. After DS21060 was implemented and the organized labor force was reduced, many people migrated to cities and unions lost their power. The so-called Marcha por la Vida (March for Life) in 1986 was the starting point of a series of defeats for the labor movement. Oscar Olivera, the author's brother and one of the main leaders of the Cochabamba Water War, recalls the march: “In September 1986, the miners' union organized their famous March for Life, which began in the high plateau and covered 200 kilometers on the way toward its goal—La Paz. The march involved thousand of miners, their families, and supporters of other sectors of society…. But the military intervened to halt the march. Without a single shot being fired, the people demobilized. In reality, this was a kind of abdication. The miners gave in to the state and that is when a new era began in Bolivia.”

- 6Olivera and Lewis, Cochabamba, 31-32.

- 7Ibid, 34-35.

- 8Ibid, 37-41.

- 9The demand for a constituent assembly was born during the historic indigenous marches and found an echo in cities during the mobilizations in 2000 and 2003. When Morales assumed control of the government, it was with a mandate to make this possible.

- 10Usos y costumbres is an indigenous customary law, which operates according to how a resource—in this case water—has been used and managed traditionally. It varies from one place to another and changes over time.

- 11Resolution United Nations General Assembly, Resolution A/RES/64/292, July 2010, https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/human_right_to_water.shtml.

- 12Article 5 in Spanish reads: “Para efectos de la protección y tutela de sus derechos, la Madre Tierra adopta el carácter de sujeto colectivo de interés público,” or “For the purposes of the protection and guardianship of its rights, Mother Earth adopts the character of a collective subject of public interest,” http://www.planificacion.gob.bo/uploads/marco-legal/Ley%20N°%20071%20DERECHOS%20DE%20LA%20MADRE%20TIERRA.pdf.

- 13Alexander Dwinell and Marcela Olivera, “The water is ours damn it! Water commoning in Bolivia,” Community Development Journal 49, no. 1 (2014): 44–52; Álvaro García Linera, “El Estado en transición. Bloque de poder y punto de bifurcación,” in El Estado: Campo de Lucha (La Paz: CLASO, 2010).

- 14Dwinell and Olivera, “The water is ours damn it!” 50.

- 15Carlos Crespo “Tipnis y Autonomia,” Bolpress (2012), http://www.bolpress.net/art.php?Cod=2012121007.

- 16The Bolivian government adopted a new constitution in 2008 following a constitutional assembly.

- 17These systems can be found all over the Americas and there are good examples of cooperation among them and public companies. See Madeleine Bélanger Dumontier, Susan Spronk, and Adrian Murray, The work of the ants: Labour and community reinventing public water in Colombia (Municipal Services Project, 2014), https://www.municipalservicesproject.org/publication/labour-and-community-reinventing-public-water-colombia; Daniel Viglietti, “Public and Community Partnership in the Americas,” Transnational Institute, January 28, 2015, https://www.tni.org/my/node/3296; and “All for one and one for all,” Transnational Institute, February 4, 2014, https://www.tni.org/my/node/3117.

- 18Dwinell and Olivera, “The water is ours damn it!” 46-47.

Residents of District 14, south of Cochabamba, digging a ditch for water pipes (Asociacion de Agua y Alcantarillado 22 de abril)

Graffiti reading "The water is the people's, damnit!" next to a group of Dalmatas, special forces brought in by the government to suppress demonstrations, February 2000 (Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida)

Protest on San Martín, one of the main streets in Cochabamba, April 2000 (Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida)

Distributing and rationing potable water in Cochabamba, 2016 (El Diario Nacional de Bolivia)