Infrastructure in

America

The A&E System

Public Works and Private Interest in Architectural and Engineering Services, 2000–2020

Download the PDF here or read on Instagram @a_and_e_system

Architects’ fame does not necessarily correlate with their power. In fact, the opposite has tended to be true. Distributed across anonymous joint ventures, tangled bureaucracies, and vested interests, uncounted designers and producers of the built environment in the United States and beyond its borders constitute a formidable system of private interest. Thanks to its inscrutability, this system has an enormous impact, reproducing and reinforcing manifold injustices even as its most visible, if increasingly limited, public manifestations remain subject to democratic checks and balances.

What does architecture look like when studied through this system? Considering the increasing number of climate-related disasters requiring federally funded mitigation and response efforts, long-stalled infrastructure proposals, and heated debates about a "Green New Deal," “Green Stimulus,” or even “Green Reconstruction,” what does this system reveal about the built environment's relationship to today's interconnected crises of mutual care, racial oppression, and climate? And what part do architects truly play?

Systems hide. Accordingly, these questions are not easy to answer. This downloadable resource for students, teachers, and professionals in the arts and sciences of the built environment — available for download here, to the right, and on Instagram at @a_and_e_system — offers a provisional portrait of the A&E System. This system’s power is well established and diffuse, which makes it both important and difficult to understand.

The study focuses on public commissions, with the relationship between the “who” of federal procurement and the “what” of architecture in mind. By highlighting specific actors — identified as regulators, managers, stakeholders, and stewards — four chapters foreground the agency and responsibility of individuals and institutions in shaping the built environment. A web of public-private partnerships, the A&E System is complex, as are the built forms it generates. Nonetheless, it remains the responsibility of architects and other professionals of the built environment to understand how this system works.

Educational and professional institutions supporting the A&E System, however, have tended to shy away from this critical task in favor of more narrow understandings of the disciplines that shape the built environment and of their agency. Some aspects of the system, which stretches from small, locally-focused firms to those engaged in massive, multinational projects, will therefore be recognizable to readers, while others might seem less familiar, or perhaps even unrelated. This document simply sketches its most visible contours by stitching together publicly available federal procurement data, corporate websites, and advertisements. The first step toward systemic change is recognizing the system.

Design by Partner & Partners

Public Works for a Green New Deal

“Public Works for a Green New Deal” assembled a cohort of nine courses from across programs at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation to consider the social, technical, and political contours of the ambitious—but still largely undefined—proposal known as the Green New Deal (GND). Supported by the Buell Center, “Public Works” was one of several initiatives within the POWER project dedicated to providing a forum for engaged, critical discussion on the role of the built environment in the GND and related proposals. Toward this end, the Center has continued to gather knowledge, materials, and perspectives that center on three related areas: linking policy with politics; working across scales; and thinking relationally and systemically.

Courses for “Public Works” were adapted to address the GND proposal directly, with all design studio sites being U.S.-based and all briefs responding directly to the text of the Green New Deal resolution. The courses also responded, in various ways, to the call for imagination in Kate Aronoff’s article, “With a Green New Deal, Here’s What the World Could Look Like for the Next Generation” (originally written for the Intercept and since republished on the POWER website). All participating students and faculty attended the "Designing a Green New Deal" event at the University of Pennsylvania on September 13th, 2019, for which the Buell Center was a co-sponsor, and a follow-up event, "Public Works for a Green New Deal," at GSAPP on September 27th.

GSAPP Faculty Responses

Listen to Buell Center Director and Professor Reinhold Martin and GSAPP Faculty including David Benjamin, Phu Hoang, Andrés Jaque, Kaja Kühl, Ariella Maron, Kate Orff, Thaddeus Pawlowski, Bryony Roberts, Marc Tsurumaki, and Douglas Woodward speak about their involvement in the Fall 2019 curricular initative.

Professor Reinhold Martin on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Associate Professor David Benjamin on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Faculty Phu Hoang on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Associate Professor Andrés Jaque on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Faculty Bryony Roberts on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Mark Tsurumaki on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Kaja Kühl on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Professor Kate Orff and Faculty Thaddeus Pawlowski on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Adjunct Professor Douglas Woodward on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Faculty Ariella Maron on Public Works for a Green New Deal

Student Presentations

On November 22, 2019, the nine “Public Works” courses gathered for a supercrit in Wood Auditorium. Students and faculty were joined by guest critics Kate Aronoff, Francisco J. Casablanca, Billy Fleming, and Gabriel Hernández Solano.

Participating Studios and Courses

Climate Design Corps: Reinventing Architecture, Labor, and Environment

David Benjamin

This studio is structured as a mini-thesis project; each student designs their own site, program, position, and 11-year impact in terms of both carbon emissions and equality. They explore new modes of practicing architecture. In addition to reimagining the approach to the climate crisis, this studio reimagines the discipline.

Being-With: Coexistence at a Planetary Scale

Phu Hoang

Rethinking public works as multi-species at both architectural/infrastructural and planetary scales, the studio proposes ecological imaginaries in response to the Green New Deal. Speculating on a carbon-free climate future in coastal Louisiana requires students to design at both habitat and planetary scales while avoiding thinking in binary terms of environmental relationships—human vs. animal, society vs. nature, organism vs. environment, even wild vs. domestic.

Transscalar Towers, The Ultra Clear-Glass Plan

Andrés Jaque

This studio interrogates the current obsession for ultra-clear glass (also known as lowiron glass) in contemporary high-end apartment and office buildings in globalizing urban settings, and the way its use is rhetorically presented as a contribution to the process of turning cities into environmentally sensitive floor-to-ceiling architectural schemes.

Structures of Care

Bryony Roberts

This studio addresses the social justice dimensions of the Green New Deal proposal, focusing on the connection between social and environmental sustainability.

Imaginative Realism: Cli-Fi, the Sublime, and the Public Imaginary

Marc Tsurumaki

This studio examines if and how the historical notion of the sublime might provide a lens through which to view our current crisis, examining the ways climate change is imagined, envisioned, and represented in order to understand how alternate narratives might be formulated and advanced.

The Climate Crisis—Imagining a Green New Deal in the Hudson Valley

Kaja Kühl

Working in the Hudson Valley, the studio operates at the regional scale and asks students to enter the discourse of urbanization beyond cities to engage unevenly dispersed socio-spatial ecosystems at multiple scales. Specifically, it explores the region’s rural/urban socio-spatial ecosystems as the site for intervention to address the global climate crisis.

Resilient Urban Design and Urban Planning Practicum: A Green New Deal for Appalachia

Kate Orff and Thaddeus Pawlowski

This course explores urban design and planning practice through the lens of resilience. It focuses on emerging approaches and strategies to climate adaptation in the built environment, and integrating ecological imperatives and social justice into next century forms of infrastructure.

Planning and the Green New Deal: A Practicum

Ariella Maron and Douglas Woodward

This course engages the proposed Green New Deal (H. Res. 109, the “GND”) from an urban planning perspective, investigating its political bases, technical feasibility, implementation strategy, and planning and land use impacts. The course approach concentrates on the socio-technical aspects of the GND as opposed to strictly technical responses to climate change, to mirror the focus of the proposed legislation itself.

For more information on the participating faculty members and courses, visit the GSAPP website.

Public Service Announcements

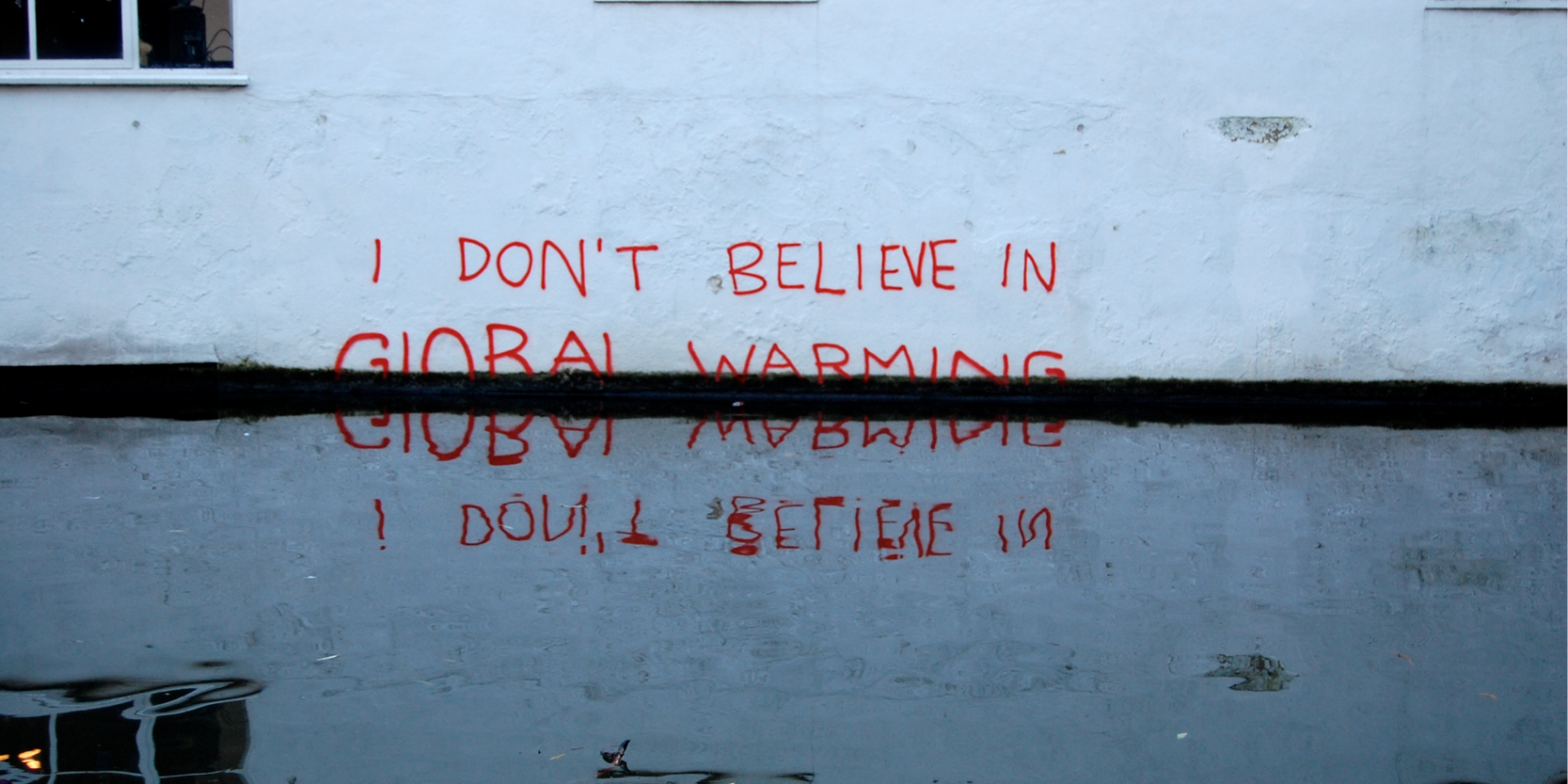

Green Reconstruction, which recognizes that climate justice is unthinkable without racial justice, requires a public sphere where economic redistribution is openly discussed. Media networks, and the stories told there, are among the most important tools for rebuilding our collective imagination to conceive of justice in this way.

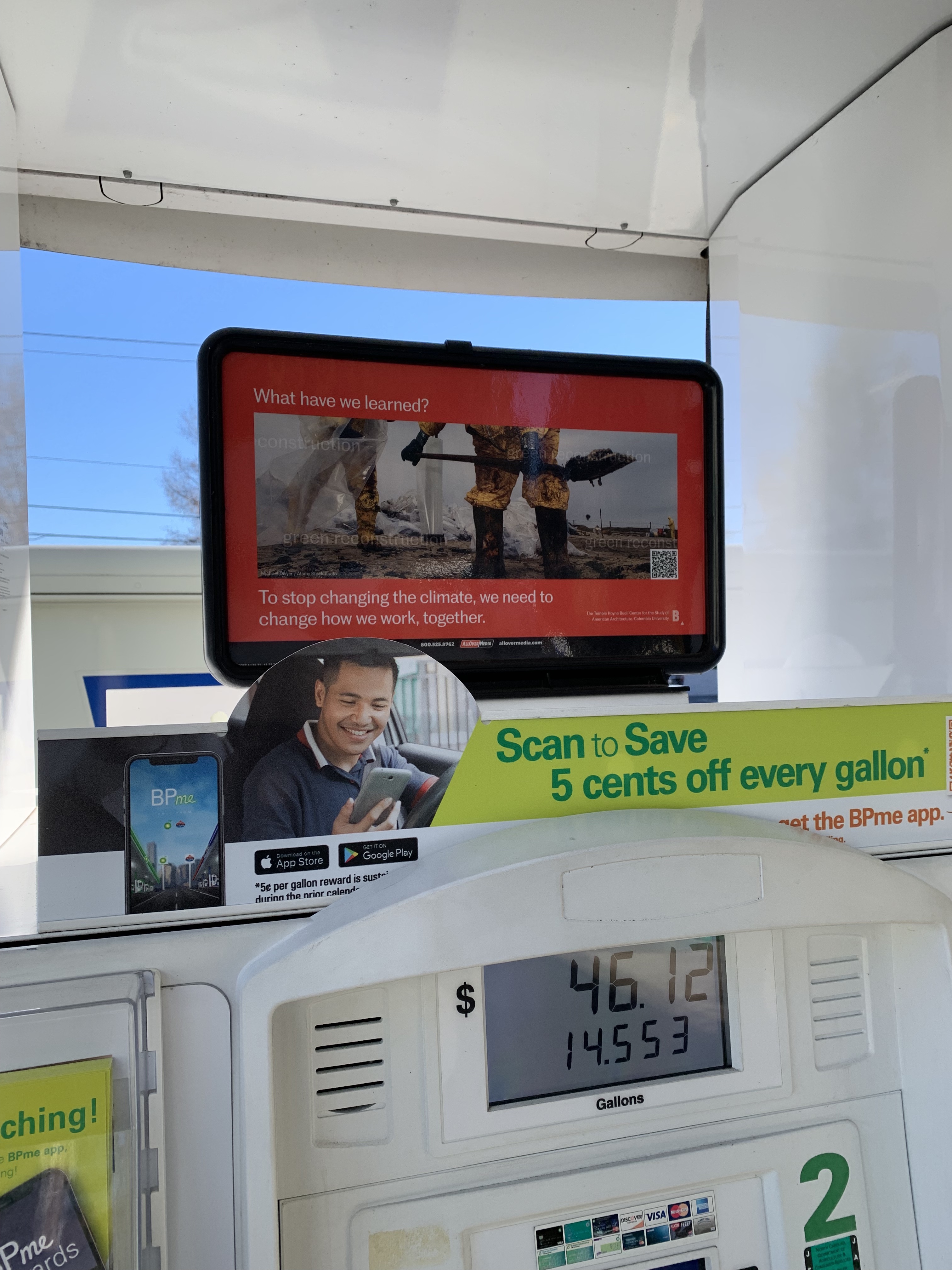

Public service announcements (PSAs) borrow private networks for the purposes of public pedagogy. In a related spirit, the Buell Center has created two campaigns, which are available to share in whole or in part. While both have been distributed through social media (Instagram | Twitter), we have further circulated the first campaign via local newspapers across the United States, and have placed the second in situ at gas stations in three cities that were featured in the Buell Center publication Green Reconstruction: A Curricular Toolkit for the Built Environment. Though the two campaigns have different, intersecting areas of focus—the first reflecting on the COVID-19 pandemic and the second on climate change—both invite the kind of imaginative rethinking that Green Reconstruction will require.

Designed by MTWTF, the PSAs build on stock images with potentially surprising readings. As a guide to systemic change, they seek to sharpen public perceptions of hidden-in-plain-sight crises that define contemporary society, and to prompt aspirations toward the solidarities that will be required to confront them. With a special focus on the intentionally weakened systems of care—housing, healthcare, and education—in everyday American life, each of the PSAs calls for reimagining these systems, and for their subsequent reconstruction.

The format—stock images of commonplace scenes with accompanying readings—can be replicated by anyone interested. Please write to us for more information, share, and create your own. Like the world to which it aspires, Green Reconstruction is a collective project.

[Image Description: Orange barricades and covered faces punctuate an outdoor scene with grey residential architecture in the background and temporary shelter in the foreground. Sequentially appearing white text on blue background, partially obstructing the image in shifting vertical bands, reads: "What color is green? The first walk-up COVID-19 testing site in Providence was located at a public school on the city's south side, where three quarters of residents are Black or Latinx and one third live in poverty. After COVID-19 comes climate change. On the front lines of both, care work is green work. green reconstruction."]

[Image Description: A flat-roofed, single-story structure is nestled closely against a brown embankment, allowing for the narrow passage of a seven-person HAZMAT-suited team, entering through what appears to be the building’s back door. Sequentially appearing white text on brown background, partially obstructing the image in shifting vertical bands, reads: "When the system fails, it works. A disaster recovery team enters the Life Care Center in Kirkland, WA in March 2020 to clean and disinfect during the COVID-19 outbreak. If housing is healthcare, this is a housing crisis. When systems fail, they show how they work, and for whom. green reconstruction."]

[Image Description: An aerial view reveals a large area of pavement with evenly demarcated rectangles, drawn in white — twenty-one are visible. Inside each rectangle are different types, colors, and sizes of tent structures. Sequentially appearing white text on yellow background, partially obstructing the image in shifting vertical bands, reads: "Inequality is designed. Rectangles drawn on a parking lot enforce social distancing at a city-sanctioned homeless encampment in San Francisco during the COVID-19 pandemic. The peaceful rationality of the solution masks the violence of the plan. green reconstruction."]

[Image Description: Darkly shaded silhouettes—of masked medical professionals on the left, and of two reflective personal automobiles in a line on the right—contrast sharply against a bright exterior beyond. One professional holds a thin swab in one hand, which extends into the window of the front car, an SUV, where its end is invisible. Sequentially appearing white text on brown background, partially obstructing the image in shifting vertical bands, reads: "This is not a test. At a COVID-19 drive-through testing facility in Washington, DC in April 2020, the automobile becomes PPE. When the plan is not to plan, austerity is a way of life. green reconstruction."]

[PSA Image Descriptions: A bright red frame surrounds the image, with white text in the frame reading "What have we learned?" above the image, and reading "To stop changing the climate, we need to change how we work, together." below it.

In the first PSA, a person in a hard hat is visible from behind standing on a ladder amongst a tangle of metal ductwork, using what looks to be a drill at one of the duct’s joints. The worker’s tool belt is full and their hoodie is brown.

In the second PSA, two workers in yellow hazard suits and boots—both largely smeared with a black substance—shovel similarly colored material into large clear plastic bags. The workers’ faces are obscured, and the sky behind them is a steely grey.

In the third PSA, a group of around eight small children are escorted under a willow tree, by hands and by harnesses, across a dirt yard toward a playground. Together with the adults that are escorting them, all present have their backs to the camera and wear neon safety vests.

Institutional information, including a QR code, is in the bottom right of each PSA.]

[PSA Image Descriptions: A bright red frame surrounds the image, with white text in the frame reading "What connects us?" above the image, and reading "To stop changing the climate, we need to change our infrastructure, together." below it.

In the first PSA, a deep blue twilight sky rests above and behind a brightly lit metal canopy, covering an area where cars are able to fuel up when connected to at least six pump stations. One white car, presumably connected to a pump, sits on the asphalt in the background.

In the second PSA, dark grey-blue water anchors a lighter grey-blue sky, with at least six large metal wind turbines connecting the two in the foreground, middle ground, and background.

In the third PSA, seen from high in the air, a seemingly large pipeline snakes from the left to the right, across a field of varying shades of green. In the middle, running from the top to the bottom of the image, a waterway offers a delicate, or not-so-delicate, counterpoint to the infrastructure under which it flows.

Institutional information, including a QR code, is in the bottom right of each PSA.]

[PSA Image Descriptions: A bright red frame surrounds the image, with white text in the frame reading "Where are we going?" above the image, and reading "To stop changing the climate, we need to change our cities, together." below it.

In the first PSA, seen from high above, a multitude of highways pass over and under one another, each covered with cars moving across the frame in every direction. The city through and over which the roadways pass is barely visible underneath and around them.

In the second PSA, it’s a sunny day, and four cars are parked on black asphalt in front of a small strip mall with a salon and arcade amongst its tenants. Two people can be seen entering the premises on the right side of the image.

In the third PSA, between five and ten nearly identical homes run along the right side of the image, receding into the background in parallel with a receding street. Parked in front of most of the homes are shiny cars, all either red or grey. Trashcans, seemingly awaiting attention, pepper the driveways.

Institutional information, including a QR code, is in the bottom right of each PSA.]

Paris Prize

Three prizes of $3,000 each are awarded to students at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation whose fall semester architectural design (MArch & AAD) studio projects most successfully comply with, interpret, and/or critically extend the terms and spirit of the 2015 Paris Agreement. Winning proposals will directly address the social, technical, political, and symbolic implications of the climate accord in an architecturally specific fashion, at multiple scales.

2020 Paris Prize Recipients:

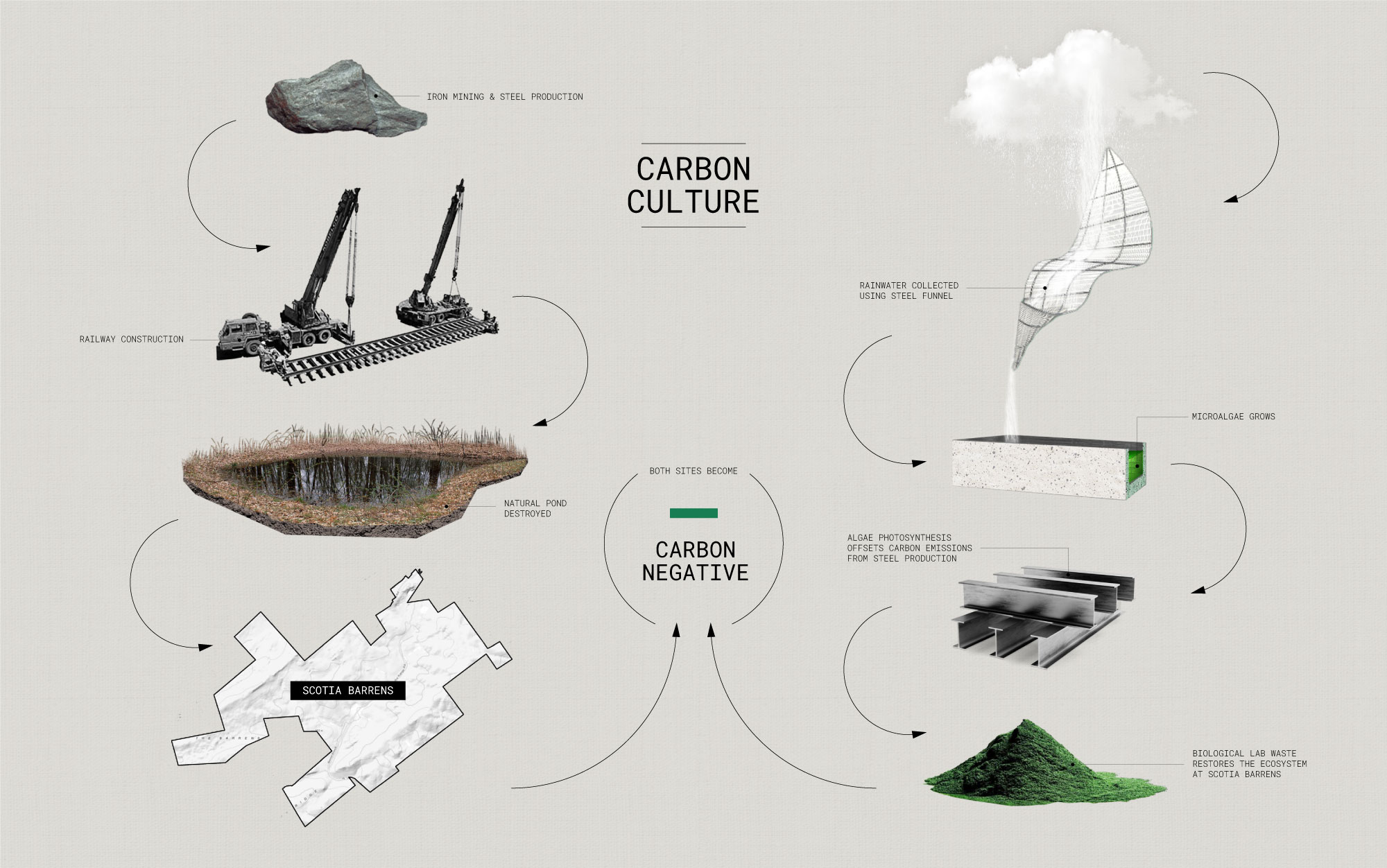

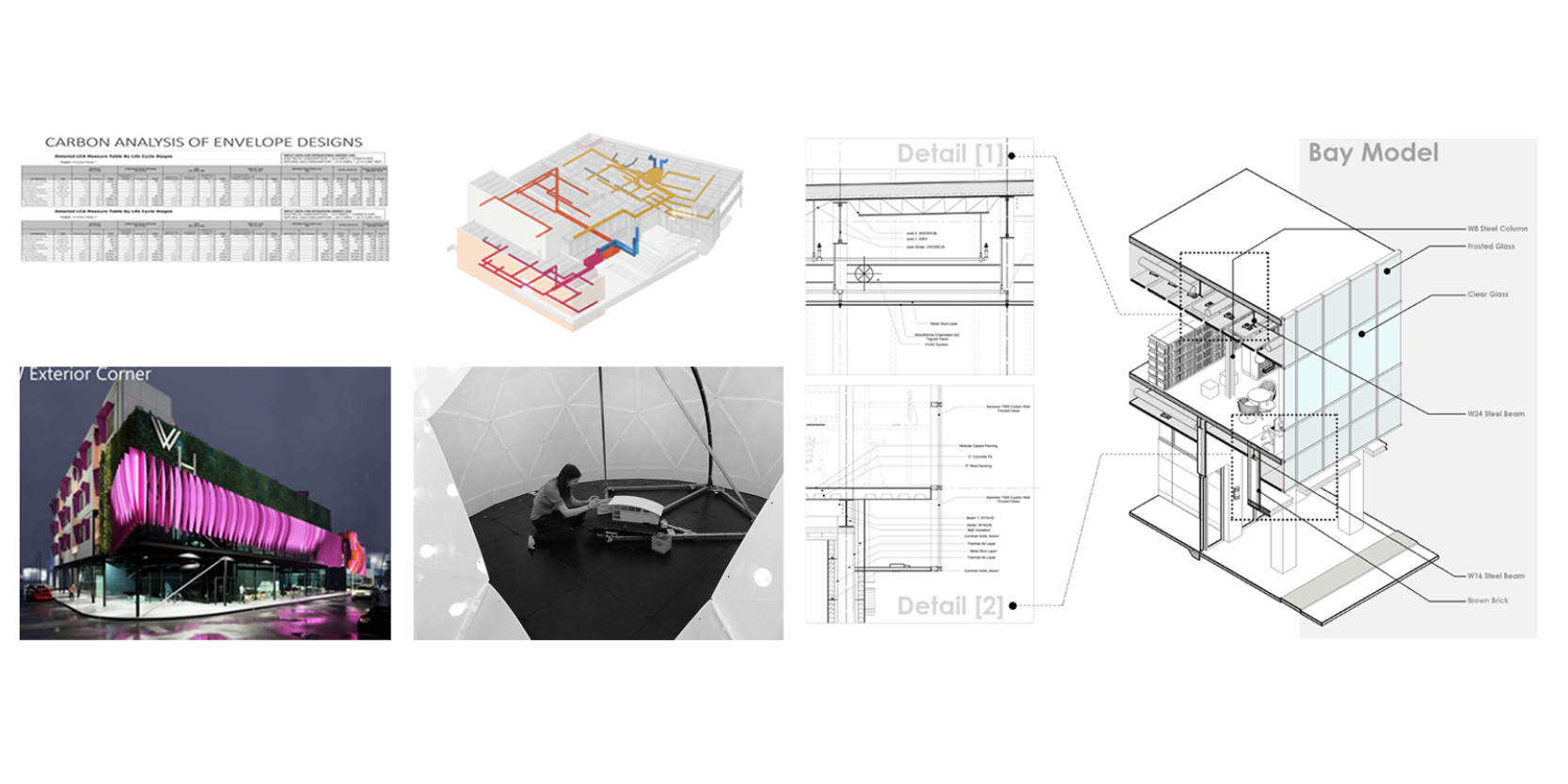

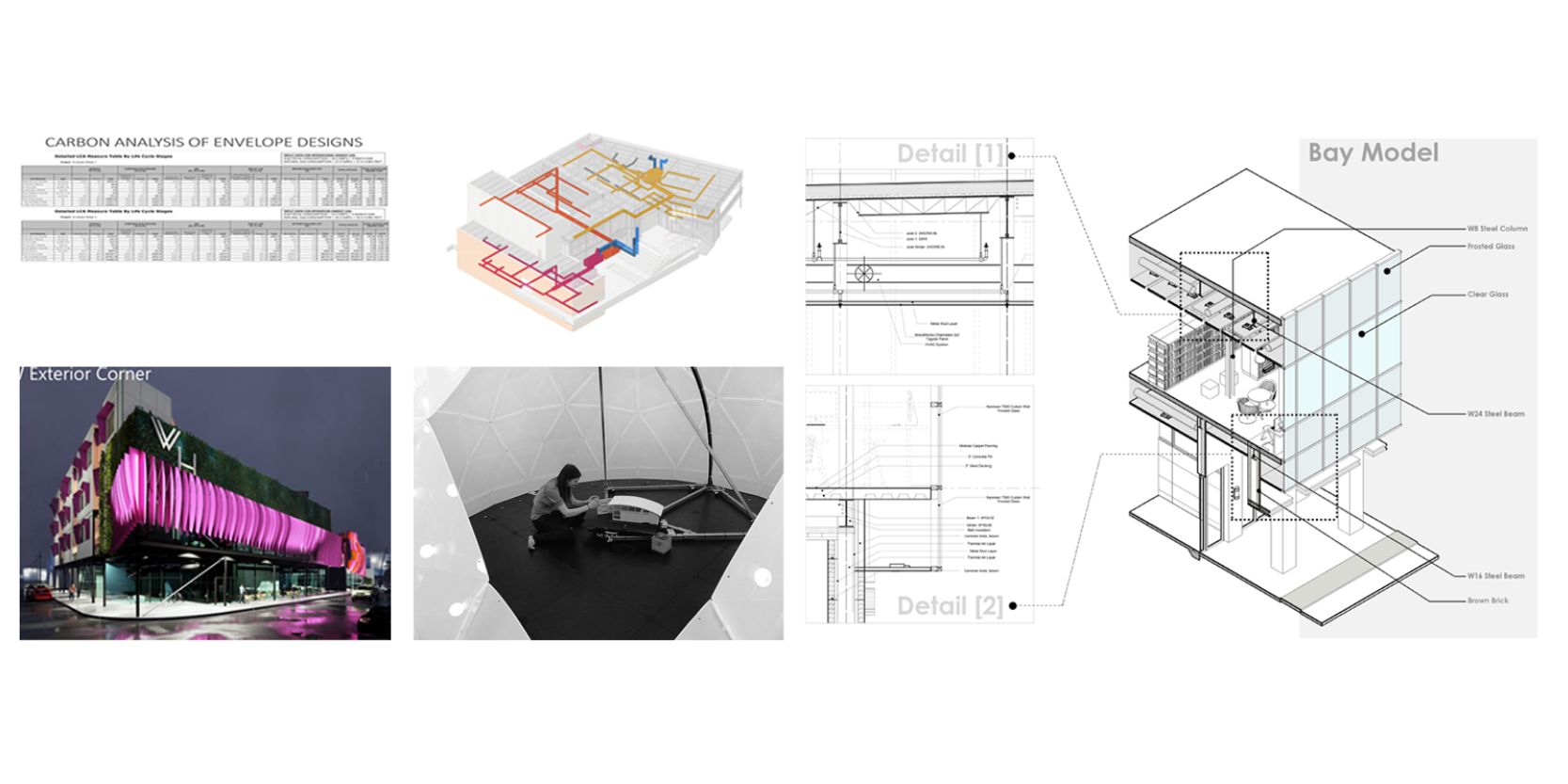

Core I Winner: "Carbon Culture" — Rose Zhang, Critic: Lindsey Wikstrom

Carbon Culture is a circular system that utilizes carbon capture and biosequestration to innovate, adapt, and improve the ecological health of two sites: places historically known for consumption and excavation. An investigation into the site of consumption, that of 29 Broadway, revealed a steel skeleton with a trail of destruction. Tracing the material to its site of extraction, the manufacturing and fabrication of steel laid waste to a ten-acre pond and unraveled the surrounding ecosystem, earning the name “Scotia Barrens.” Carbon Culture redeems this steel—an unremedied biological cost—by introducing microalgae to assimilate CO₂ through self-cultivation. Using a structural algae-infused bioplastic funnel, rainwater is channeled into a man-made pond capturing 17,204 kg of CO₂ annually. Supplanting the vacant retail space is a public maker lab, advancing innovation in construction practices using algae. Biological lab waste is processed into fertilizer and transported to Scotia Barrens, restoring its ability to host life by improving the soil health. Carbon Culture increases public awareness, collaboration, and accountability in each building’s response to climate change.

Core I Finalist: "Emergent Harvest" — Stephen Zimmerer, Critic: Alessandro Orsini

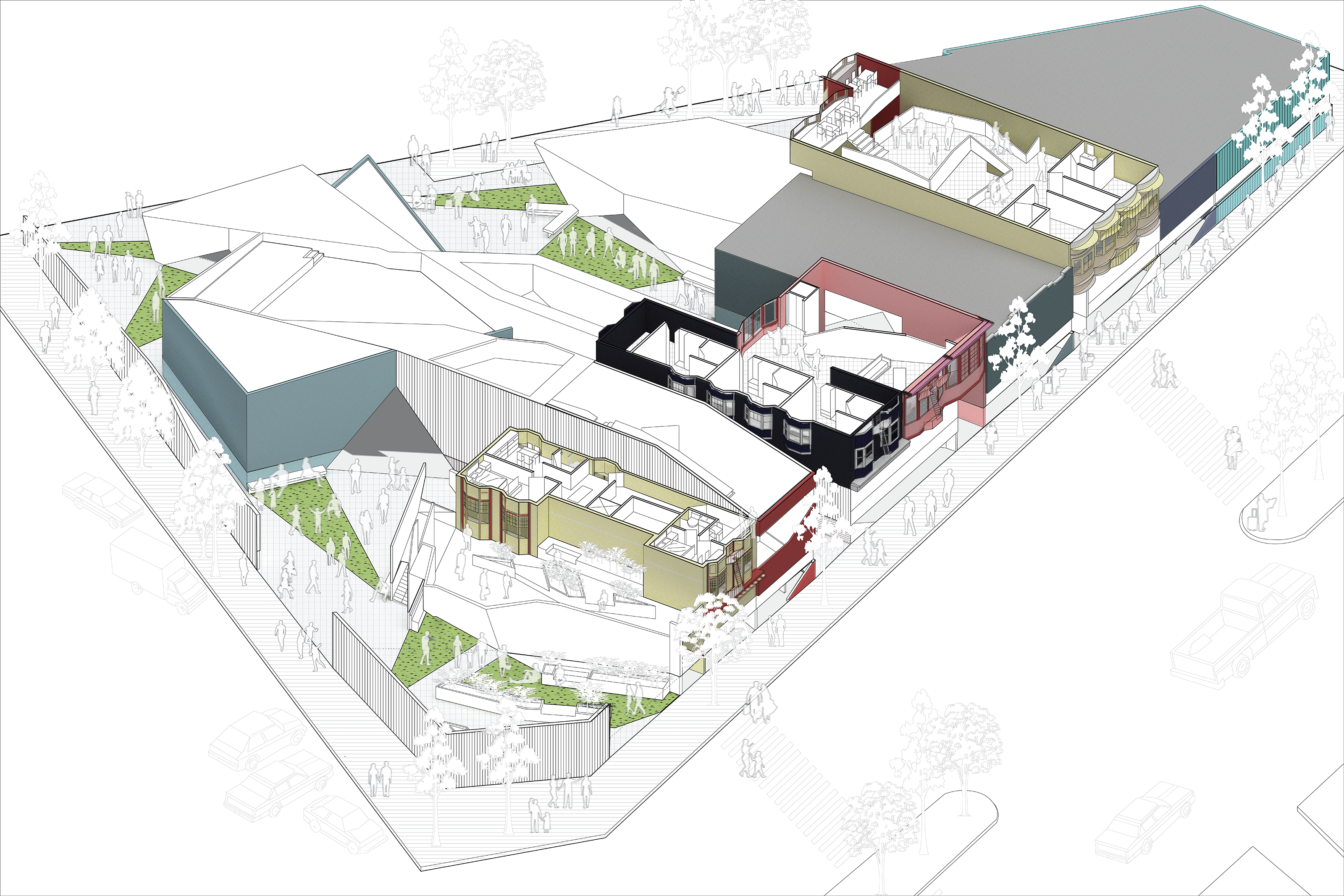

Core III Winner: "Units of Care" — Adeline Chum & Max Goldner, Critic: Hilary Sample

Units of Care calls for affordable housing that is both efficient and detailed, both humble and resourceful, and looks to provide care through every scale and program. It calls on sustainable design to assume more than flashy greenscapes, and looks toward thoughtful, and sometimes invisible, acts of care. We organized ground floor programs that could render maintenance as visible and important, enable access to sites of repair, reconstitute resilience by amplifying existing community support networks, and balance community amenities between street-facing and more internal areas.

Bridging the gap between efficiency and diligence that all too often comes with affordable housing design through precision, sensitivity, and care, we envision what affordable housing might offer. What should new housing developments bring to new and existing residents alike? What should be minimized, and what can be maximized?

Core III Finalists: "A Micro-Macro Community" — Gizem Karagoz & Lucia Song, Critic: Annie Barrett; "Urban Vegetated Filter" — Yongyeob Kim & Karen Matta, Critic: Erica Goetz

Advanced Winner: "Energy Tower in the Park" — Emily Ruopp, Critic: Gordon Kipping

Energy Tower in the Park creates an Architectural Activism that seeks to mitigate issues of income inequality, climate vulnerability, and social vulnerability. It achieves this through net-positive building alterations while also mobilizing an unemployed workforce to participate in the emerging economy of renewable resources and technology in a way that promotes the most vulnerable populations first. While it is relatively easy to conceive of sustainable single-family homes, working with tall buildings without horizontal real estate requires a rethinking of the way we typically see renewable technology. To achieve this, vertical solar farms, vertical axis wind turbines, and inline hydropower turbines are employed. Ultimately, this project is an experiment that attempts to alleviate the effects of climate change, mobilize an undervalued workforce, create community connection, and generate disposable income for residents of NYCHA housing, thereby making them less vulnerable and improving their living conditions.

Advanced Finalists: "Bamboo Living Project: Makoko Iwaya Community" — Ochuko Okor, Critic: Nayhun Hwang; "Materializing Air: An Infrastructural Network of POPs Research and Care" — Audrey Marie Dandenault & Alek Tomich, Critic: Nayhun Hwang; "Public Luxury: Water as a Medium for Care" — Mark-Henry Decrausaz, Critic: Bryony Roberts

2019 Paris Prize Recipients:

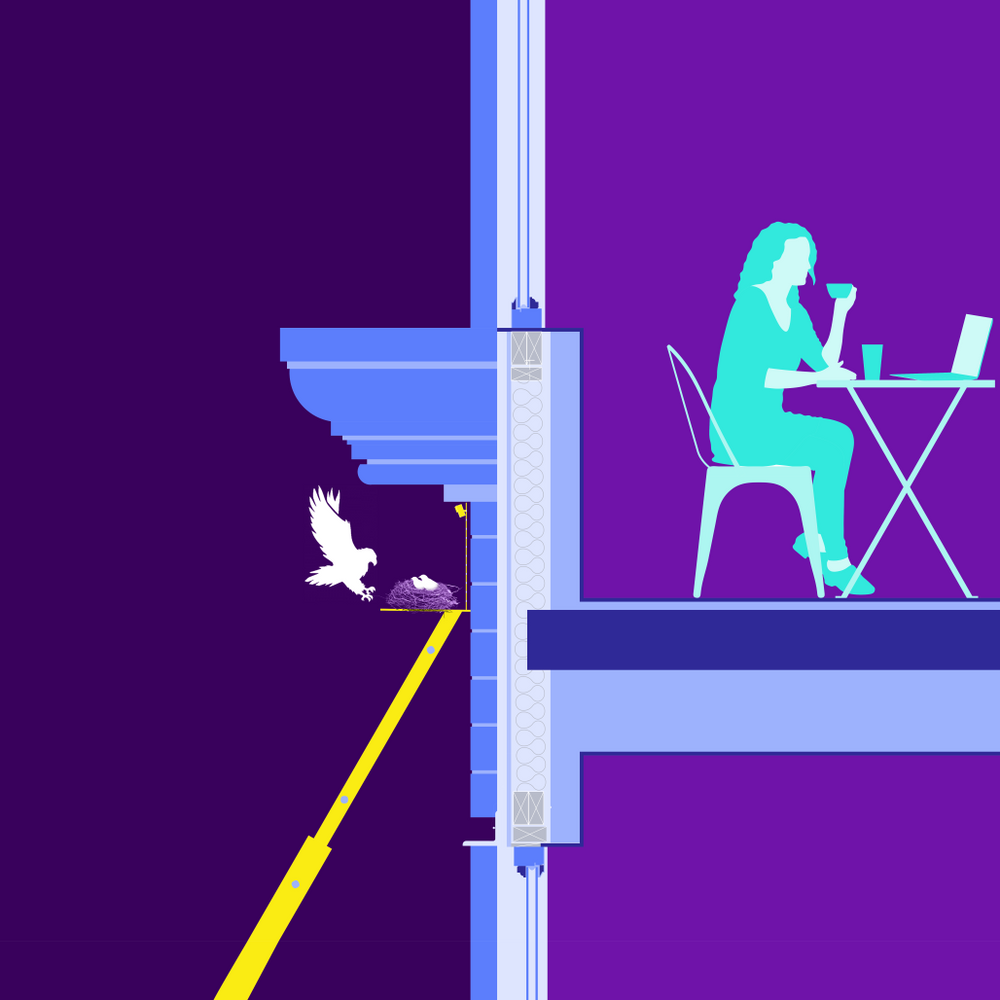

Core I Winner: "Birdway on Broadway" — Aya Abdallah, Critic: Lindy Roy

“Birdway on Broadway” is an ornithological research station that is built on one of New York’s oldest roads. The project’s aim is to create a supportive environment for breeding, feeding and sheltering of birds. It’s intended to work in tandem with a classmate’s rat habitat project, which together, enhances a “predator-prey” system. The designed system will attract and grow bird populations that have become endangered through human construction and resource extraction, specifically Red Tailed Hawks - predators that feed off rodents, reptiles and squirrels. In addition, the associated system will rebalance the rat population without the use of harmful chemicals. By creating new habitats for them along Broadway, their relationship can serve as a self-sustaining pest control system to the city. Birdway on Broadway could be presented as an offset alternative, but instead of offsetting carbon, the designed system will offset biodiversity footprints. This explains the flyer format of some of the drawings, to be distributed to locals around Broadway to donate and offset their biodiversity footprint by using relatable and scalable comparisons. In this case, $30 could offset a flight from New York to San Francisco, which is the equivalent of 0.3 MSA.ha (Means Species Abundance).

Core I Finalist: "Quilted" — Adeline Chum, Critic: Alessandro Orsini

Core III Winner: "Slow Water" — Alice Fang & Angela Sun, Critic: Daisy Ames

Due to the lack of access to regular maintenance and inability for water infrastructure to adapt to increased population growth and change in climate, “Slow Water” puts forth a new model for collecting, cleaning, and delivering water to residents in the South Bronx. Borrowing from cultures celebrating water as a holistic performance with the body, such as Japan with onsens/sentos, water became the main vessel for enhancing health. This proposal for future living provides housing for single mothers sharing lifestyles and goals of raising their children within a supportive community, pushing for parent-child and parent-community interpersonal relationships guided by a spectrum of individual and shared water experiences. Our project hopes to bridge something beyond an economic model of housing sustainability, striving for human driven empathetic spaces.The programs are interspersed among the living units, weaving in and out between spaces as a way to connect public and private, wet and dry, shared and individual.

Core III Finalist: "ID_ID Houses" — Vera Savory & Marcell Sandor, Critic: Galia Solomonoff

Advanced Winner: "Toxic Entanglements" — Christopher Spyrakos, Frederico Gualberto Castello Branco & Frank Mandell, Critic: Andrés Jaque

Toxic Entanglements utilizes architecture as a vehicle for the articulation of existing alternative waste treatment processes tying space, funding and actors of various scales in order to enable its implementation. Matter and resource are exchanged, produced, consumed and expelled. What is toxic for certain species nurtures the next, through a continuous circular system. An assemblage of 10 processes that function in unison regulating and providing for each other. An infrastructure that arranges ecosystems through biological and mechanical processes that circulates matter in various states of transformation. We analyze existing environments that are tied to waste management today to envision a possible New York. 50 Hudson Yards was chosen for the implementation of this first prototype due both to location at the interstice of unsustainable waste infrastructure, toxic sites, and problematic relations to animals, and as an effort to reground the East Yards, in an equitable sustainable future for New York.

Advanced Finalists: "Greenlining East Harlem" — Kachun Alex Wong & Lucy Navarro, Critic: Mabel Wilson & Jordan Carver. "High Time for Low Tech" — Julia Pyszkowski, Critic: David Benjamin

2018 Paris Prize Recipients:

Core I Winner: "A Green Commodity" — Nelson De Jesus Ubri, Critic: Anna Puigjaner

A Green Commodity proposes green streets that carve into the existing architecture of the Upper West Side. The objective is to imagine how streetscapes could blend with buildings around them while reducing carbon emissions and energy consumption. Three aspects of the shared and collective in New York City were analyzed. Community gardens were researched to understand how public spaces empower local communities. The tenement typology was then analyzed to comprehend how the lack of daylight and air in interior spaces influenced the use of alleyways, bathrooms, and kitchens. And lastly, studying the value of NYC trees determined by the Department of Parks in relation to the services provided by them: stormwater interception, energy conservation, air pollutant removal, and carbon dioxide storage. This research led to three design strategies: carving into buildings to bring in light and air, creating porous edges between green streets and the adjacent architecture, and using the financial support of developers to plant trees and finance this greening effort.

Core I Finalist: "The Great Billboard Walk" — Yaxin Jiang, Critic: Benjamin Cadena

Core III Winner: "Self-Sustainable Micro-Community" — Ge Guo & Qi Yang, Critic: Ilias Papageorgiou

We think that sustainability lies in the lifestyle people live. We propose the self-sustainable attitude towards living: A lot of things you consume in the architecture comes from the architectural system itself: light, wind, water and food. We transform the traditional large-scale public space into a series of domestic scale courtyards which nourish diverse activities and encourage the residents to maintain their own courtyards. People enter each unit through the roof landscape, which advocates the culture of walking and leads to a healthier and energy-saving lifestyle. The boundary of units is not fixed. All the living space is flowing in between the fixed elements: light wells, service cores, circulation cores, and shear walls. The design approach opens myriad possibilities of space usage and each unit is unique. In this way, the built structure could achieve its best efficiency.

Core III Finalist: "Upstairs - Downstairs, Living Together on Three Planes" — Alexandros Prince-Wright & Yoonwon Kang, Critic: Hilary Sample

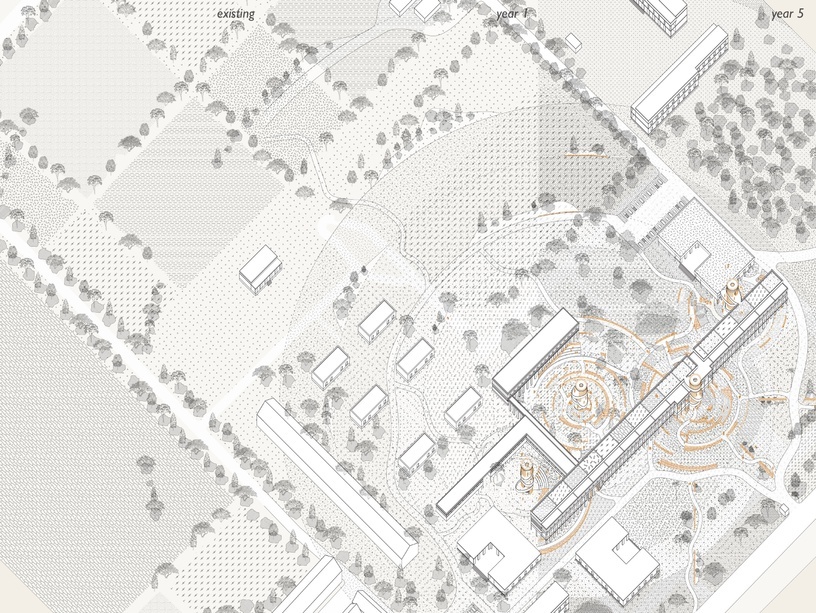

Advanced Winner: "ESAMo: Constructing New Grounds for Agricultural and Social Transformation in Tunisia" — Mayrah Udvardi, Critic: Ziad Jamaleddine

The Ecole Superieur d’Agriculture de Mograne (ESAMo), was built in 1952 to train Tunisians in industrial agricultural methods and cement France’s hold on the country’s agro-economy. While a building itself cannot be held responsible for international slow violence, it can reveal the intentions and unintended consequences of top-down planning. My design challenges the French framing of the pastoral and rigid delineation of the groundline, offering a phased approach to diversify agricultural production and reintegrate students with the landscape. At the center of this new program are four seed libraries, built from stone of the hollowed campus ground floor. This process of deconstruction and rebuilding will, itself, become part of the curriculum, as students, teachers, builders, and farmworkers integrate their knowledge. Over time, this collective work will become pixelated throughout the campus; the formerly static groundline will become temporally dynamic, punctuated by retaining walls, bunds and terraces for cultivation and water collection. This process can be applied to other nodes of environmental degradation in Tunisia, redistributing agency and material resources to those who have been most impacted by imperialist development and climate change.

Advanced Finalist: "Five Opportunities for Planetary Acupuncture" — Kevin Hai, Critic: Andres Jaque

2017 Paris Prize Recipients:

Core I Winner: "Armadillo" — Lizzy Zevallos, Critic: Brandt Knapp

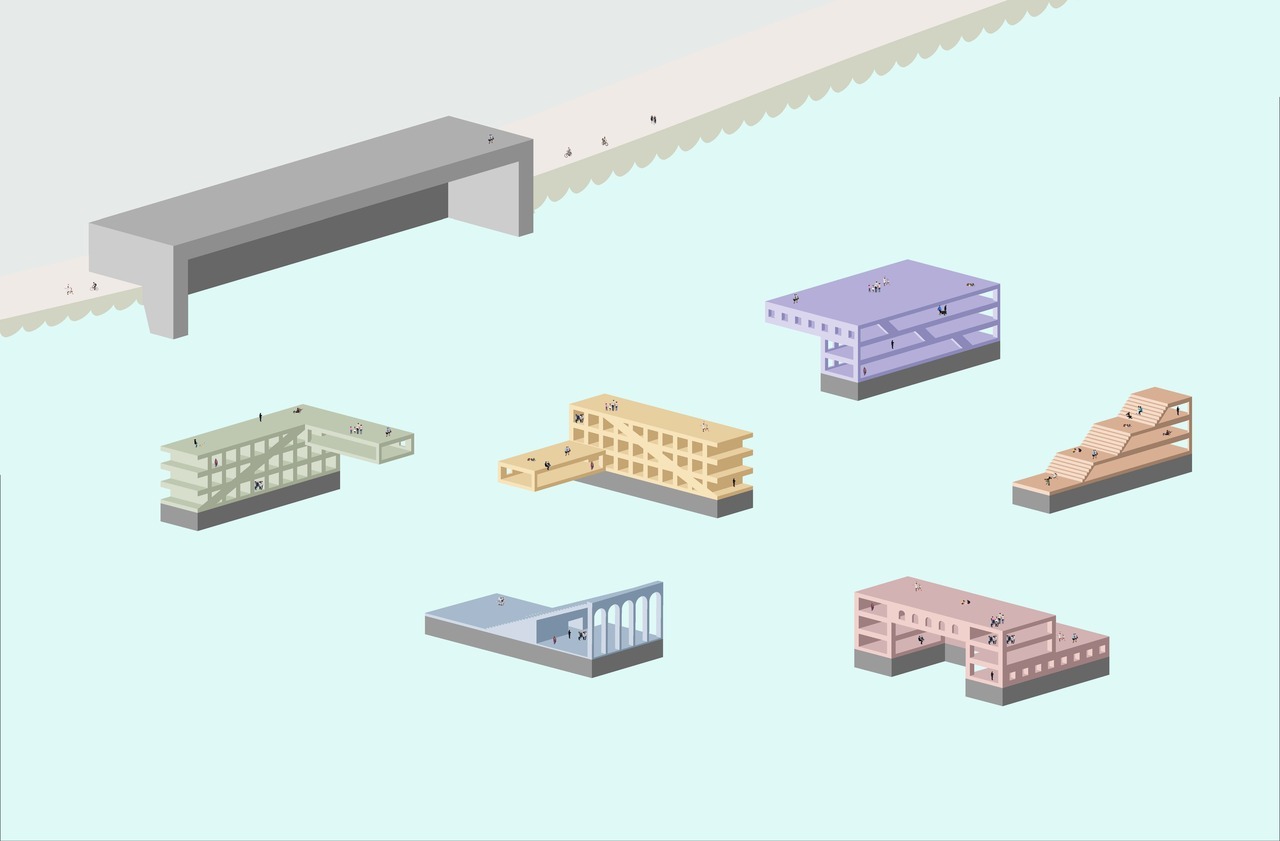

The Armadillo aims to set an example for sustainable building while making New York City adaptive to a changing world through socially productive means. It is located on the East River at 14th Street adjacent to the Con-Edison power plant. Barricaded within a concrete shell during the winter and extreme weather, it is an incubator space for art, dance, theater, and science. In the summer, it expands into six autonomous floating components, each with its own public programming potential as a stage, exhibition space, and more. The components dock up around NYC and North Jersey, making art accessible to various communities. The Armadillo ensures its own longevity through its adaptive concrete shell that protects the components during extreme weather. It also protects Con-Ed from storm surge. Lastly, it is a template for many similar structures to form a flood wall chain around lower Manhattan, which may otherwise be underwater within our lifetimes.

A Green Commodity proposes green streets that carve into the existing architecture of the Upper West Side. The objective is to imagine how streetscapes could blend with buildings around them while reducing carbon emissions and energy consumption. Three aspects of the shared and collective in New York City were analyzed. Community gardens were researched to understand how public spaces empower local communities. The tenement typology was then analyzed to comprehend how the lack of daylight and air in interior spaces influenced the use of alleyways, bathrooms, and kitchens. And lastly, studying the value of NYC trees determined by the Department of Parks in relation to the services provided by them: stormwater interception, energy conservation, air pollutant removal, and carbon dioxide storage. This research led to three design strategies: carving into buildings to bring in light and air, creating porous edges between green streets and the adjacent architecture, and using the financial support of developers to plant trees and finance this greening effort.

Core I Finalists: "Urban Farm" — Gauri Bahuguna, Critic: Iñaqui Carnicero; "Forest Farms" — Marc Francl, Critic: Tei Carpenter; "Instrument of Nature" — Serena GuoGe, Critic: Tei Carpenter

Core III Winner: "Sharing Economy" — Emily Po & Quentin Yiu, Critic: Galia Solomonoff

We believe sharing within a housing complex can double the fulfillment of the user by just creating half of the space. Through a series of studies on household objects, we have developed a concept of sharing based on usage and programming. Therefore, we work towards reducing overall construction area as well as increasing operational efficiency of those spaces. Thus, through the idea of sharing, this project reduces carbon footprint through eliminating underutilized appliances within the flat and relocating them in a common space, which is more efficient and social at the same time. Realizing food as a social construct, we introduce dine-in restaurants, cafes and informal outdoor areas in the public plaza. Along with the community kitchens, these spaces encourage social activities and gatherings.

Core III Finalist: "The Open Core" — Mayrah Udvardi & Sarah Rutland, Critic: Daisy Ames

Advanced Winner: "Culture Culture" — Christopher Gardner, Critic: David Benjamin

The coming biological age should be seen as an opportunity to reassess “sustainability”. For my project, a research complex in the sugar cane fields outside Campinas, Brazil, I’ve employed the grown material of bacterial cellulose, the leathery by-product of the bacteria commonly found in Kombucha. While utilizing bacterial cellulose is demonstrably positive environmentally, my goal with this project is to engage the non-quantifiable: the inherent politics, morality, and perceptions surrounding a new building materiality. To interrogating these manifold issues, I have created a series of narratives profiling seven different actors and their relationship to the research complex building. These narratives, each represented through their own unique media, define a scenario while also informing the design. In finding the edges of our current relationships and tweaking them, I believe we can achieve a much broader impact. Perhaps then we can begin to address climate change with the necessary urgency.

Advanced Finalist: "The Brine" — Lincoln Antonio, Critic: David Benjamin

For more information, see buellcenter.columbia.edu.

Buell Center Paris Prize 2020

2020 Core I Winner: “Carbon Culture”—Rose Zhang, Critic: Lindsey Wikstrom

Core III Winner: "Units of Care"—Adeline Chum & Max Goldner, Critic: Hilary Sample

2020 Advanced Winner: “Energy Tower in the Park”—Emily Ruopp, Critic: Gordon Kipping

Buell Center Paris Prize 2019

2019 Core I Winner: “Birdway on Broadway”—Aya Abdallah, Critic: Lindy Roy

2019 Core III Winner: “Slow Water”—Alice Fang and Angela Sun, Critic: Daisy Ames

2019 Advanced Winner: “Toxic Entanglements”—Christopher Spyrakos, Frederico Gualberto Castello Branco, and Frank Mandell, Critic: Andrés Jaque

Buell Center Paris Prize 2018

2018 Core I Winner: “A Green Commodity”—Nelson De Jesus Ubri, Critic: Anna Puigjaner

2018 Core III Winner: “Self-Sustainable Micro-Community”—Ge Guo & Qi Yang, Critic: Ilias Papageorgiou

2018 Advanced Winner: “ESAMo: Constructing New Grounds for Agricultural and Social Transformation in Tunisia”—Mayrah Udvardi, Critic: Ziad Jamaleddine

Buell Center Paris Prize 2017

2017 Core I Winner: "Armadillo" — Lizzy Zevallos, Critic: Brandt Knapp

2017 Core III Winner: "Sharing Economy" — Emily Po & Quentin Yiu, Critic: Galia Solomonoff

2017 Advanced Winner: "Culture Culture" — Christopher Gardner, Critic: David Benjamin

Green Reconstruction

What is Green Reconstruction? It is an outline, an open work, for the repair of a world ravaged by three intersecting crises—of mutual care, of racial oppression, and of climate, all intersecting in turn with economic inequality—that moves along two axes, the Green axis of ecological transformation, and the gilded axis of material redistribution, or Reconstruction. The Green axis refers to the ecological and economic ambitions of proposals like the Green New Deal and its counterparts around the world, all of which merit serious academic and public attention. The second axis recovers the unfinished project of what W. E. B. Du Bois called, in Black Reconstruction in America (1935), “abolition democracy,” and with it, the political-economic restructuring of a system for which the expropriation of Black and brown lives is business as usual, as racial and ecological apartheid remain global norms.

More specifically for the arts and sciences of the built environment, Green Reconstruction names a new curriculum, a potential change of course. By this the Buell Center recognizes the central role of professional, academically sanctioned expertise in constructing and maintaining a status quo, including a status quo nominally devoted to perpetual innovation. To mean anything and to change anything, Green Reconstruction must speak from below; but to endure, it must find its own designers, planners, and technicians. Such figures, both scholars and practitioners, link the powers below with the powers above, with the aim of supplying technical equipment with which to make things change.

We support these efforts first by inviting any and all to join a concrete conversation about what might change and why and how. In recent years, the Buell Center has attempted to convene parts of that conversation, with detailed studies of the “right to infrastructure” in sites of racialized dispossession like Flint, Michigan, and of the states of emergency by which democratic self-governance was withheld, again along racial lines, from hurricane-torn New Orleans and Puerto Rico. We have co-hosted a public assembly in Queens to discuss the real, multi-scalar implications of the Green New Deal, and sponsored coursework at Columbia to explore its potential and its limits. Cases and occasions like these link up into a network of inputs, a constellation of site-specific conflicts and their provisional resolution, that draw the outlines of a larger, more collective effort to define change. These local efforts only begin to capture the full scope of the individual problems they explore. But taken together, they confirm the extent of the current crisis and indicate some of its key dynamics: not merely privatization, but de-democratization; not merely racist expression, but racially organized dispossession; not merely climate denial, but the knowing, profit-driven embrace of a fossil-fueled future.

We propose to assist in this change of course by changing professional curricula. By gathering specialists in the professions of the built environment, part of whose job is to impart meaning to that environment and to make it work, the Buell Center aims to show how these curricula might be modified with tools designed expressly not to repeat a deadly status quo but rather, to model societal transformation both symbolically and materially. As signaled in the Buell Center’s Green Reconstruction public service announcements, this is a civic undertaking, governed by a spirit of cooperation among educators, students, and publics with different and sometimes competing interests. Today’s multi-dimensional crisis requires us to rethink together the social, economic, and ecological order devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic in a manner that repairs the damage, amends injustice, and averts still worse. It requires us to ask how to erase longstanding inequities made clear as day, when safety, comfort, and care for some has meant heightened risk for countless others.

How to heed the warning, as fossil-fueled climate change forces overexposed populations onto front lines redrawn before our very eyes? How to see what links the absence of planning with planned exploitation? Racial oppression with ecological apartheid? Public health with environmental justice? Healing the planet with healing society?

To assist in teaching these questions and developing their provisional answers we have fashioned, with the help of many, this toolkit regarding new curricular infrastructures for professional education in the design and planning of the built environment.

Our larger goal is twofold:

- To educate ourselves, our colleagues, and our students into ways of thinking and acting that link professional responsibility with societal change.

- To outline pedagogical frameworks and courses of action for others to adopt and make their own.

Please join us.

Design by MTWTF

Unbroken Windows

A digital archive tracing the spatial cultures of Broken Windows policing

The Broken Windows theory of policing — promulgated in New York City in the early 1990s — relies on the contentious assertion that increased surveillance in often disinvested, majority-minority urban areas, and draconian responses to small “disorderly” infractions therein, will serve as a bulwark against future criminal behavior. But before windows are broken, they must first be designed as unbroken. And before neighbors are targeted, their neighborhoods must first be envisioned as property — rather than lives — needing protection. Though the prominence of Broken Windows policies has in many ways abated, the theory’s material and imaginative force remains woven into society all around us.

What does one see when they look at a public housing development? What does one feel when their car window is approached by a person asking for money? What does one know about the relationship between safety and “disorder”? Any possible answers to these questions are contingent on one’s individual experiences. And those experiences, in turn, are contingent on the spaces — and cultures — in which they occurred. A resident of public housing inevitably feels differently about said housing than someone who has never been inside. The owner of a car is differently comfortable than someone in search of basic necessities. What counts as “disorder” in a neighborhood long ignored by those with power is different from what’s permissible, or even encouraged, at the seat of that power.

The incomplete but evocative annotated sources collected on the project website attempt to trace the contours of a particularly potent moment of cultural production in New York City in order to more easily identify, denaturalize, and ultimately change its ongoing effects in the spaces around us. The six initial category tags: “Research 1961–1993,” “News,” “NYPD,” “Arts & Culture,” “Elections,” and “Legislation” indicate just some of the social realms in which Broken Windows circulates. With short, framing summaries and certain passages highlighted in the sources themselves, our aim is not simply to better explain the original and still impactful cultural context of Broken Windows, but to gesture toward a new one. Rather than recapitulating debates about the theory of policing — which have largely been decided even if they continue in new forms — this archive aims to read between the lines of that debate’s formative stages. Logical fallacies, emotional assertions, and prejudicial assumptions feel just as familiar as the built spaces that they informed. At the same time, the perhaps less-than-familiar fact that those spaces remain, and are often reproduced today, is newly deserving of critical attention.

Connected to its ongoing project, “Green Reconstruction,” with this collection and any conversation it generates, the Buell Center is interested in addressing the violent, yet often obscured, relationships between race, “resilience,” and architecture. Understood from its inception as incomplete, the material on the project website has been gathered (largely online) in support of ongoing conversations that are reimagining what justice means — and how it is built — in the United States today. Produced during the summer of 2021 in dialogue with the “care,” “repair,” and “justice” themes of the Queens Museum’s “Year of Uncertainty” (YoU), any subsequent responses and additions to this archive will be collected and displayed by the Museum as a part of the YoU in a time, place, and manner of their choosing.

Ultimately, "Unbroken Windows" is intended as a reminder of the manifold ways in which design participates in the racialized cultures of safety and security that permeate the built environment. Whether active or passive, this participation has effects that cannot be ignored, for which responsibility must be taken.

Local Course Development

INFRASTRUCTURAL IMAGINARIES:

Between Design, Nature and Politics

Columbia University GSAPP

Fall 2018

Instructor: Tei Carpenter

[Parallel course taught by Jesse LeCavalier at the New Jersey Institute of Technology]

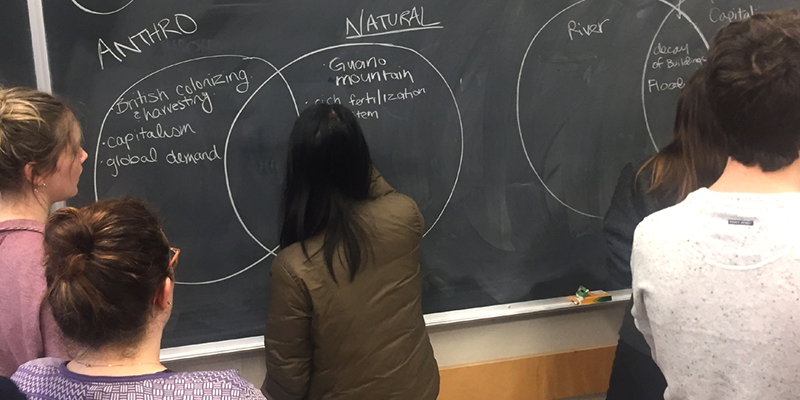

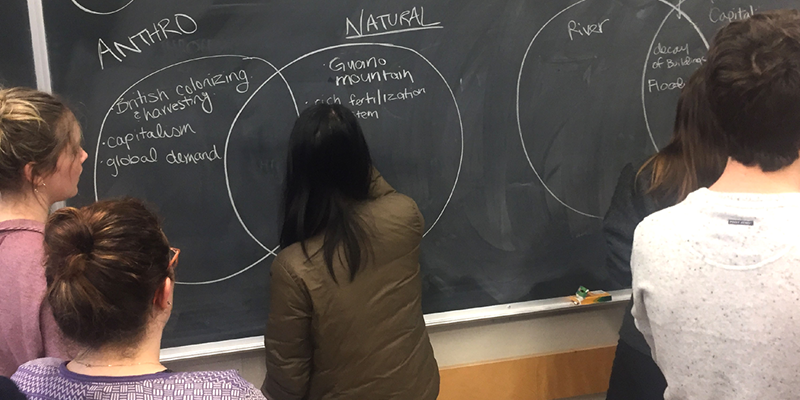

Infrastructural systems are not merely technical but also capable of generating desire and fantasy. This seminar explores the way in which infrastructure might occupy these multiple (and at times competing) roles in order to better understand how it has been thought of historically, how it is thought of now, and how it might be thought of otherwise going forward. Within the context of the the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture’s ongoing research initiative, Power: Infrastructure in America, this seminar reflects on the current state of infrastructure in the United States through an examination of its recent history and offers a set of thematic tools to understand infrastructure as it relates to nature and politics.

The course looks at a series of built and speculative case studies by architects, landscape architects, civil engineers, policy makers, and urban designers, to better understand how design operates within infrastructural systems. These case studies focus on the ways infrastructure shapes the built environment through, for example, the mediation of resources, including water, waste, and energy. The course is particularly interested in investigating—and potentially developing—a heuristics of infrastructure, i.e. ways we might engage it as designers through, for example its aesthetic dimensions and systematic qualities.

AESTHETIC STATES:

Architecture's Multi-Nationalisms

Columbia University GSAPP

Spring 2019

Instructor: Mark Wasiuta

Multi-Nationalism

Most of us have never been this saturated with signs of nationalism or this aware of its infrastructures, architectures, and spaces. Through the current government shutdown, border wall hysteria, images of rallies in Europe and America, and the rising trend that political theorist Wendy Brown calls “apocalyptic populism,” nationalism has entered the daily news cycle, political discourse, and both the American and global social imaginary with alarming ferocity in the last years.

Yet, despite these spatial demarcations and moments of eruption that appear directly or indirectly linked to nationalism, and despite its seeming ubiquity and currency, nationalism is disarmingly elusive. Almost every theorist or writer of nationalism contends with its multiple and contradictory personalities. Although it is identified with repressive, racist, xenophobic, and even fascistic states and movements—both historical and contemporary—nationalism was once also identified with post-colonial state formations and liberation struggles.

Moreover, in its most recent iterations, nationalism acquires multiplicity through its globalism. Nationalism is global because almost every country—from Greece and China to the UK and the USA—has been impacted by its own particular form. It is also global in that its current resurgence as a populist movement is the byproduct of globalized economies and global neoliberalism. David Harvey describes our current nationalism as a political tool that offers compensation for the erosion of whatever privilege or benefits, real or illusory, was attached to nationhood. The elusiveness of nationalism results from its internal contradictions, complex history, and divergent associations. Yet nationalism is primarily elusive because the nation, faced with erosions, is itself ever harder to delineate, describe, or define with concrete certainty.

Architecture

Against the backdrop of the simultaneous resurgence of nationalism and the erosion Wendy Brown names “waning sovereignty,” the seminar will track both historical theorizations and contemporary speculations of architectural nationalism. For Brown, waning sovereignty is most clearly discerned in border walls and other forms of national fortification. These structures have both expressive and functional dimensions. They guard against incursion and entry, while also announcing the enclosure, protection, and insularity of the state. Further, as Brown recognizes, the walls’ expressive dimension reveals a primary anxiety, a “tremulousness” of state security, that underlies these defense systems. The walls are not only spatial inscriptions of nation and statehood, but also talismanic objects—they call up the force of the state and the coherence of the nation at the moment of its greatest vulnerability.

Similarly, this seminar will focus on the architecture of nationalism to glimpse the complexes of global finance, climate, refugee populations, communications, law, and the myriad other systems and relationships against which the nation and nationalism are positioned. In the seminar we will read texts that help us identify, locate, and examine the forms of architecture, infrastructure, and media, that—like the walls President Trump wants to build and that Wendy Brown has catalogued around the planet reveal the conditions and frictions between the nation and the forms of internationalism that erase, efface, and dissolve it.

Active, Banal, Spectacular

Nationalism is often portrayed as an action—the formation, consolidation, or demarcation, of state or ethnic territory—and a set of credos and sentiments. It is political philosophy, territorial instrument, and an atmosphere of beliefs and ideologies. This soft atmosphere of nationalism is distinct from the hardness of its monuments. We can use the term spectacular nationalism to describe these monuments as well as border walls, national museums, and military operations. In contrast, banal nationalism describes those objects at the edge of perception and perceptibility: bureaucracies, anonymous federal buildings, postal uniforms, and license plates. In both spectacular and banal cases, nationalism is conjured by beliefs, concrete signifiers of national identity and history, and their systems of transmission and reproduction. Nationalism is architecture, media, and territory folded together to form an aesthetic political technology.

Accordingly, we will consider nationalism as an active modifier that not only inflects thought and perception, forms political subjects, but that also alters architecture and spaces. With readings from within architecture and architectural history—as well as readings across a range of other disciplines—this seminar, then, probes the matter of nationalism by asking what nationalist discourses activate spatially, materially, and infrastructurally. As such, building proper will be one historically privileged site of nationalist attachment and representation. Yet, as sovereignty dissipates (and multiplies) so do its objects and its territories. The multi-nationalisms of the title reference this dissipation and multiplication as well as the financial girding of both nationalist and globalist discourses.

We will use the sessions to trace how nationalism has been thought, perceived, and mobilized in and through architecture. At the same time, will use the readings, topics, and discussion to reconceive nationalism and architecture through issues such as the documentary state, biometric identification, sovereign chemicals and pollutants, and the national construction of vision and perception. Rather than assume that architecture and nationalism form a clearly identifiable object or field, we will study how these two terms put each other in suspension and into new alignments in order to also ask what nationalism allows us to see of architecture—its agency, utility, and relation to power in various forms anew.

Course Development Prize in Architecture, Climate Change, and Society

Education in architecture and urbanism is well positioned creatively and critically to address the exigencies of climate change. However, pedagogical methods that prioritize immediate applicability can come at the expense of teaching and research that explore the sociocultural and ecopolitical dimensions of the crisis. This, in turn, ultimately limits the range of approaches addressing climate change in professional practice. Columbia University’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture is therefore issuing, together with the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, a competitive prize in recognition of exemplary course proposals on the theme of “Architecture, Climate Change, and Society.”

From history seminars to visual studies and from design studios to building technologies, the wide variety of course offerings at schools of architecture is a testament to the diversity of perspectives, skills, and tools that ultimately comprise quality work in the field. In contrast, the urgency of the unfolding climate crisis—especially as it intersects with calls for environmental and racial justice—can seem to demand a singular focus that is antithetical to humanities-based critical inquiry or to longer-term creative and technical endeavors. We seek the kind of realism, however, that redefines problems and leaves room for the imagination. Successful proposals for this Course Development Prize in Architecture, Climate Change, and Society will include methods and themes that innovate within their institutional setting—asking hard questions of students that are equal in weight to the hard questions being asked of society in the midst of a global pandemic as it continues to grapple with the intertwined causes and effects of climate change.

This proposal is related to a multi-year Buell Center project entitled “Power: Infrastructure in America,” which seeks critically to understand the intersections of climate, infrastructure, and architecture. Objects of intense political, social, and economic contestation, technical infrastructures distribute power in both senses of the word: as energy and as force. Concentrating on the United States but extending internationally, “Power: Infrastructure in America” opens overlapping windows onto how “America” is constructed infrastructurally to exclude neighbors and to divide citizens. But infrastructures can also connect. Organized in a modular fashion as an open access resource for learning, teaching, and acting, the contents of the project website—power.buellcenter.columbia.edu—enable visitors to better understand the complex webs of power shaping our lives and the lives of others. It is in this spirit that the prize aims to contribute to the development of intersectional pedagogy on the theme of “Architecture, Climate Change, and Society” in America today. Change begins with connecting the dots.

Are you interested in joining a network of faculty teaching architecture, climate change, and society? PLEASE SIGN UP

For all prizes after 2022, see the Buell Center website

2022 WINNERS

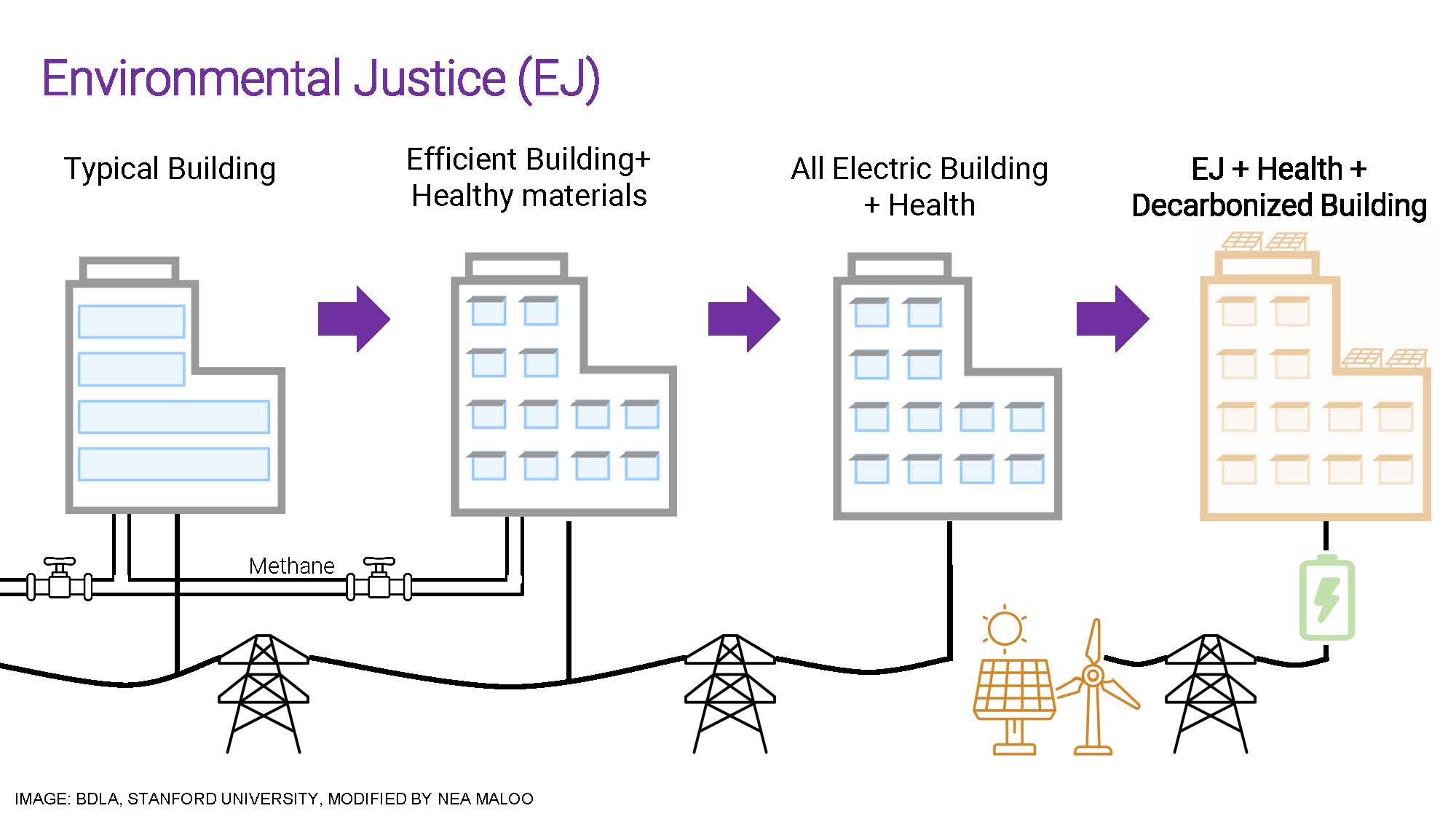

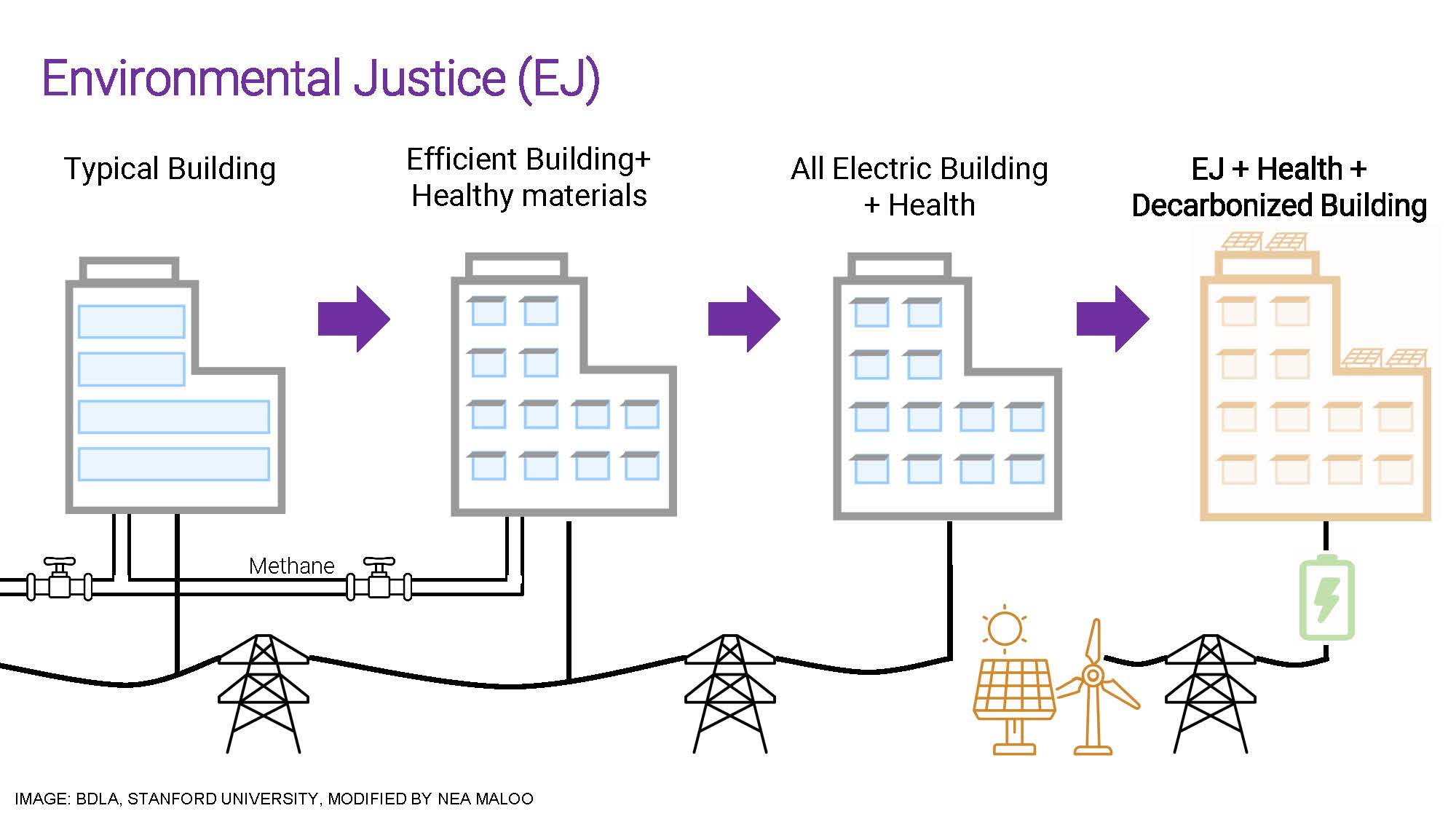

Environmental Justice (EJ) + Health + Decarbonization

Nea Maloo, Howard University

(Image Credit: BDLA, Stanford University, modified by Nea Maloo)

The Environmental Justice (EJ) + Health + Decarbonization will be a new inter-disciplinary course in the College of Engineering and Architecture, Howard University, for architects, engineers, and environmental studies major students. The course aims to put sustainable building practice at the center of environmental health, justice, and social equity. This course is intended to equip the students with the knowledge of building decarbonization and environmental justice, to be the future leaders in sustainability.

Globally, the embodied carbon emissions from the building sector alone produce 11% of global emissions and has huge impact on the environment. It is also evident that climate change has differing social, economic, health, and other adverse impacts on underprivileged populations. Under the broad umbrella of climate justice, the inter-disciplinary education will offer an overview of the use of technology tools, including the energy simulation modeling, collected data, healthy building material and design approaches in architectural design. Additionally, the students will learn theory and practice of building decarbonization as foundational approach to environmental justice. The goal is to design buildings with holistic strategies with Decarbonization and healthy building material which promotes the climate justice within the architecture profession to the broader local and global community.

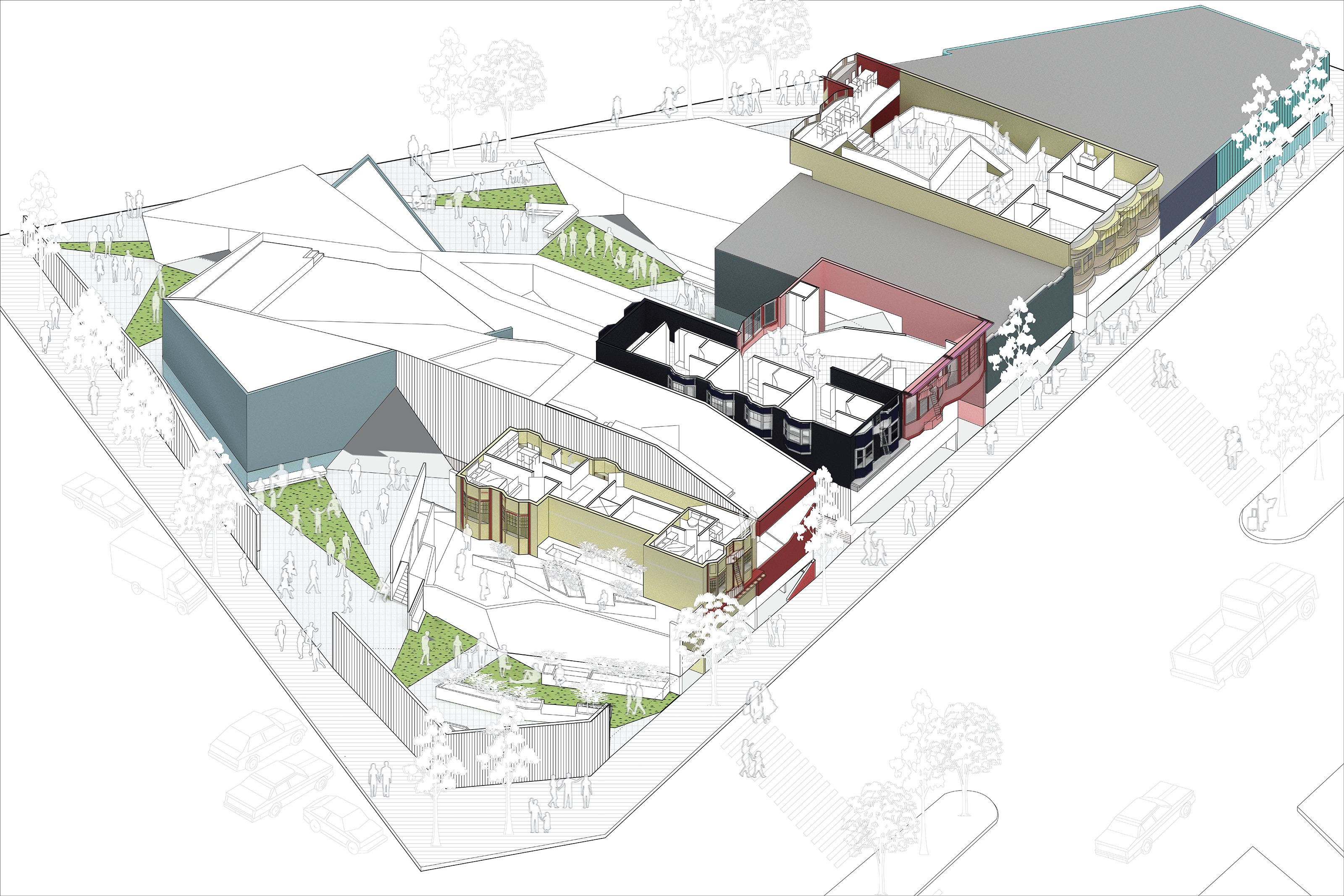

Decommodifying Ownership

Janette Kim, Brendon Levitt, & James Graham, California College of the Arts

(Image Credit: Carlos Garcia and Yue Liu, project diagram for the Reframing Property studio taught by Janette Kim, fall 2021.)

Decommodifying Ownership is a proposed cluster of coordinated courses at the Architecture Division at California College of the Arts that bridges across design studio, building technology, and history and theory curriculum streams in the B.Arch, M.Arch and Master of Advanced Architectural Design programs. These three courses will reflect on colonial legacies of dispossession instituted by the enclosure of land and the dislocation of the byproducts of extractive economies. In response, they will ask how the decommodification and commoning of land and resources can recapture energy, water, materials, and nutrients—all to sustain regenerative economies in communities whose labor and knowledge have long been mined for the creation of wealth. These courses will highlight their own unique methodologies—with an emphatic belief that each curricular track is a site for both conceptual and pragmatic investigations—while identifying sites for cross-pollination. In this way, the goal is to model speculative, new techniques for interdisciplinary architectural practice that is ever-more critical in the face of climate change.

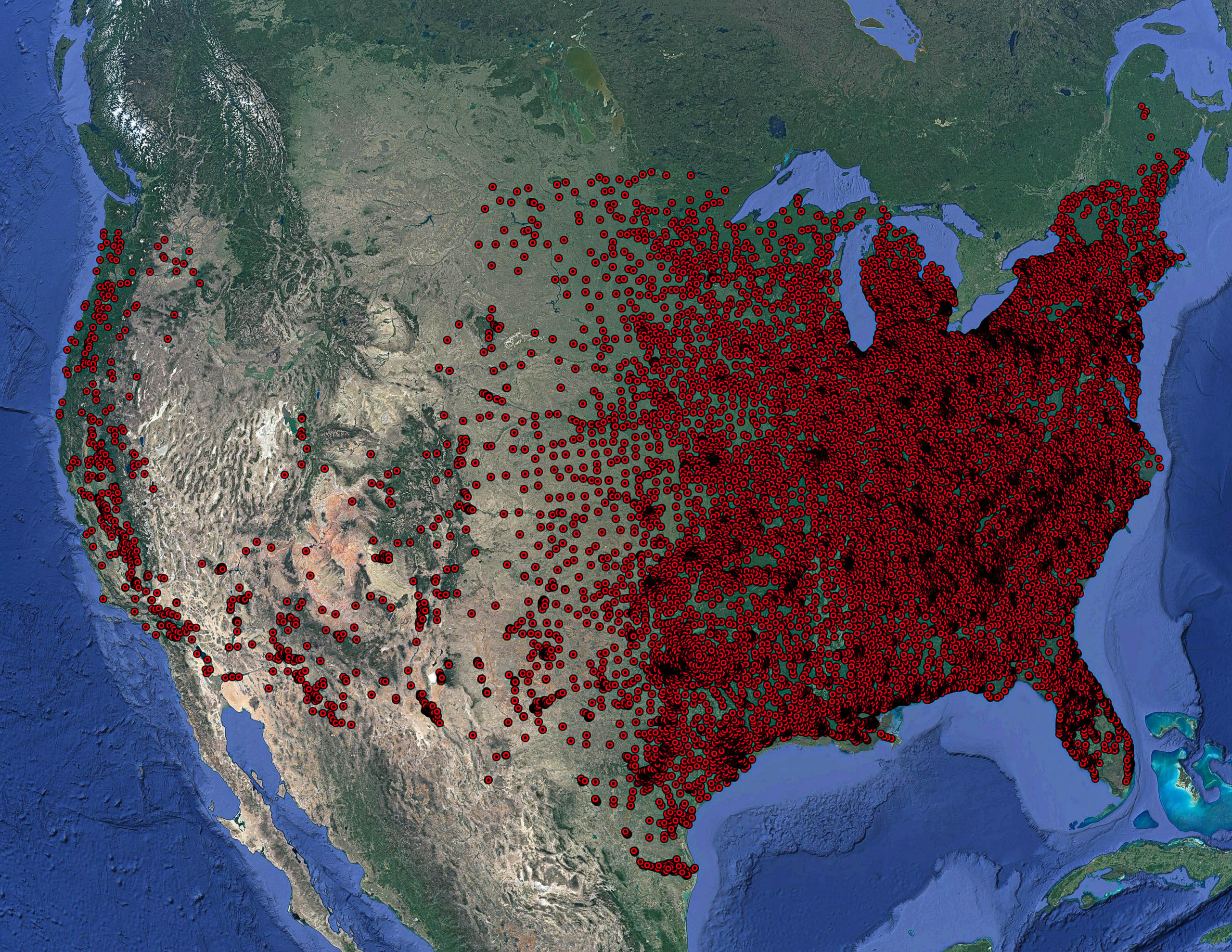

Mono-Poly-Dollar

Lindsey Krug, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Sarah Aziz, University of Colorado Denver

(Image: Ana Sandoval and Michelle Barrett)

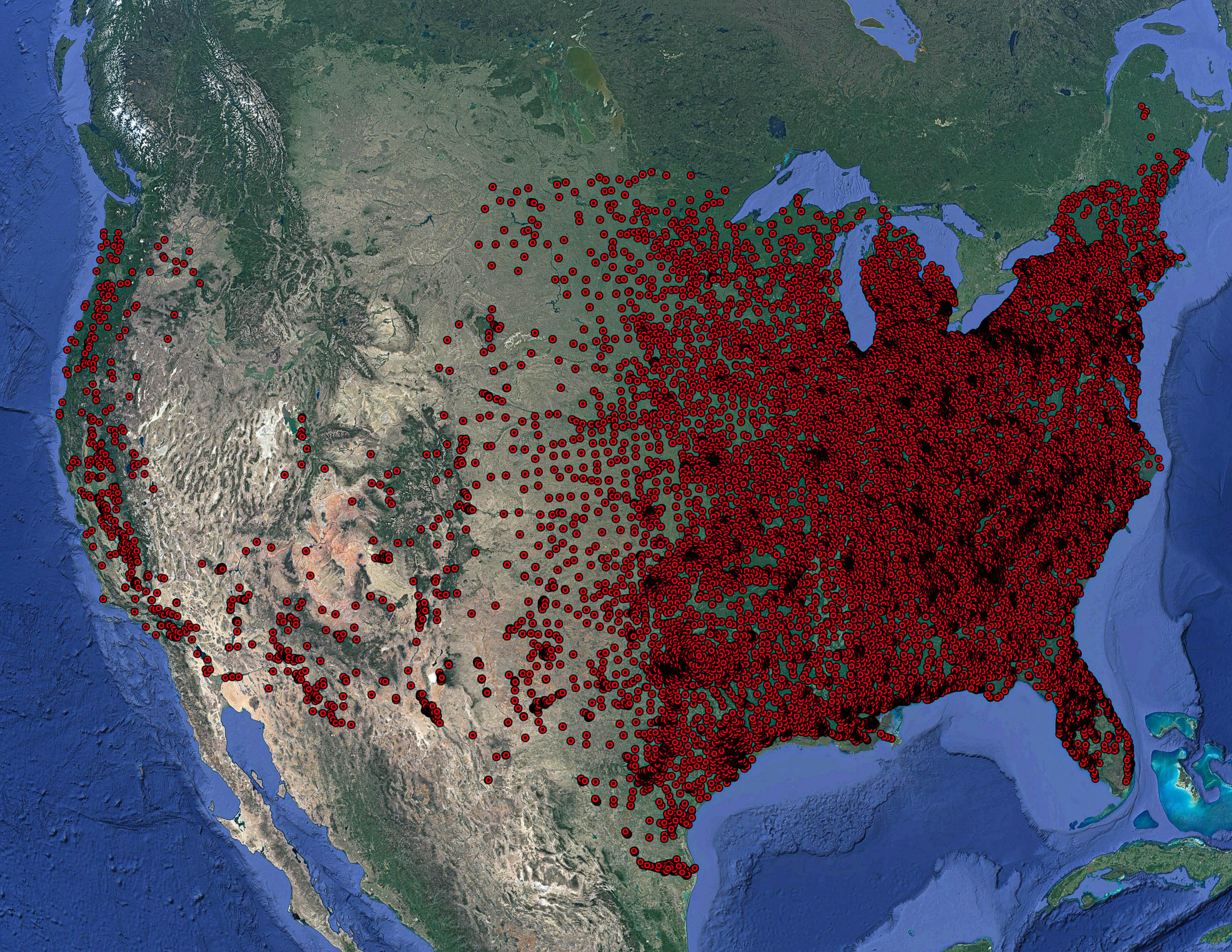

Mono-Poly-Dollar is an interdisciplinary research and design studio, operating at both the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) and the University of Colorado Denver (CUD), that uses Dollar General Corp (DG), the largest and most influential of the American dollar store triumvirate – Family Dollar, Dollar Tree, and Dollar General – to examine the country’s environmental, economic, and racial fault lines, and highlight the understudied small-box vernacular typology as a weapon of discourse and agent of climate activism.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Denver, Colorado are geographically poised to document the distribution of Dollar General’s presence in the U.S. as they trisect the drastic gradient from the densely populated DG-landscape of the American East, Midwest and South, to the sparsely populated DG-landscape of the American West. The course requires students to address the subject matter neutrally and arrive at socio-spatial positions and projections by traveling to a cross-section of the 17,000+ DG stores and distribution centers across the country and see firsthand how the retail empire affects large-scale commercial practices and mom-and-pop-corner-shop small-scale domestic realities.

Given its geographic scope, even a small shift in the invasive dollar store’s response to the climate crisis can have a large impact, and by critiquing the organization’s commercial, agricultural, and architectural strategies, students propose ways DG can provide an antidote to the silent crisis they contribute to.

Deep Geologies: Material Encounters in Texas

Brittany Utting, Rice University

(Image Credit: Victoria Sambunaris – Untitled (Pipes), Monahans, Texas – 2012)

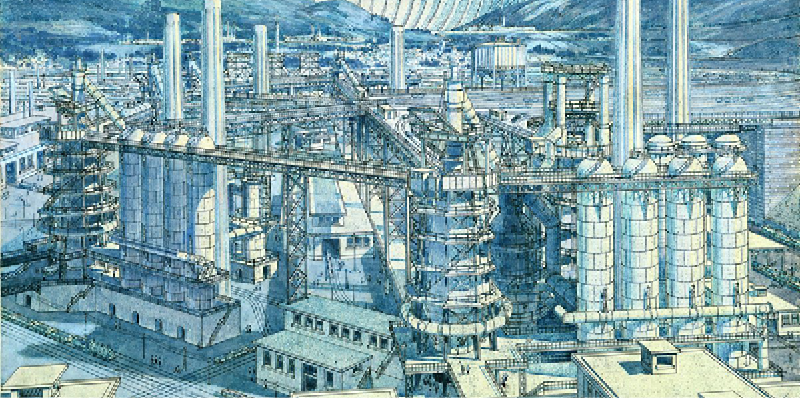

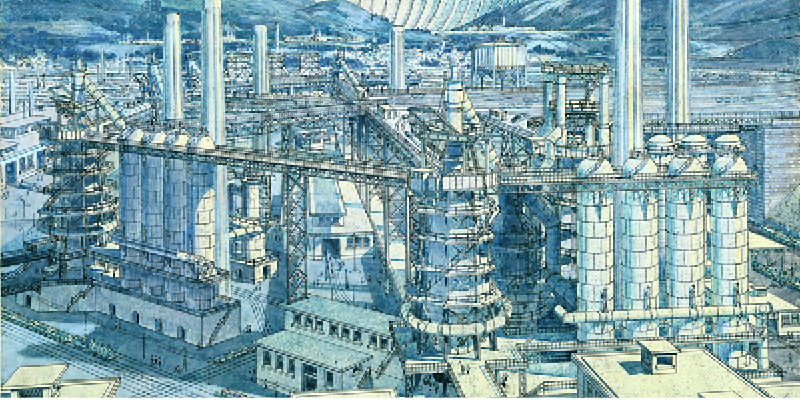

Geology is a conception of the planet’s surface as thick, resource-rich, and energy-latent, forming slowly in the “deep time” of the earth. Laced within its dense layers of rock and shifting plates, the crust contains the raw materials and carbon fuels of the technosphere: bands of iron ore, veins of mineral deposits, seams of coal, and vast fields of oil.

Our everyday worlds are sourced from these geologies—fracking, cracking, mining, drilling, processing, and burning—feeding a supply chain essential to the production and powering of the built environment. Critically, the materials themselves have specific qualities and attitudes, producing a complex infrastructure of capital, energy, and heat. Yet while these geologies constitute the substructure of carbon modernity—determining its urban scales, circulatory flows, and organizational forms—they also devastate landscapes, bodies, and climates.

Deploying spatial and material tactics to intercede in these extractive processes, this studio seeks to trouble the persistence and durability of the hydrocarbon toward a deeper conception of geology: a planetary assemblage of landscapes, ecologies, organisms, technologies, and atmospheres. Learning from Anna L. Tsing’s concept of the “liveliness” of materials, Deep Geologies looks to the entanglement of extraction and the built environment to imagine new architectures for terrestrial care. Working in the context of Texas, this studio imagines how architecture can participate in a just transition to a post-carbon future, asking how the built world can more radically engage with agendas for environmental justice and geological repair.

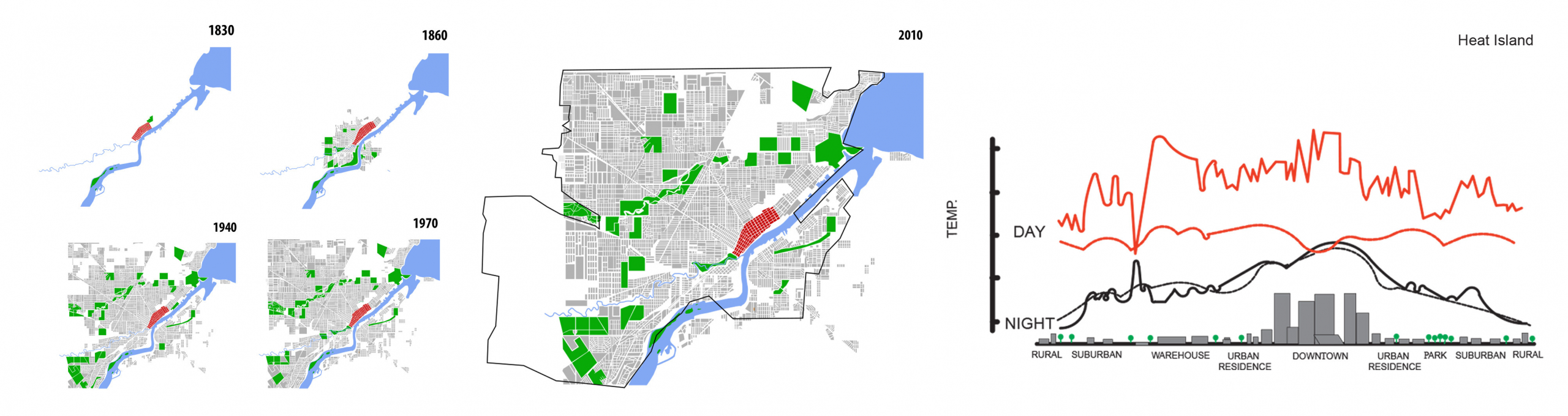

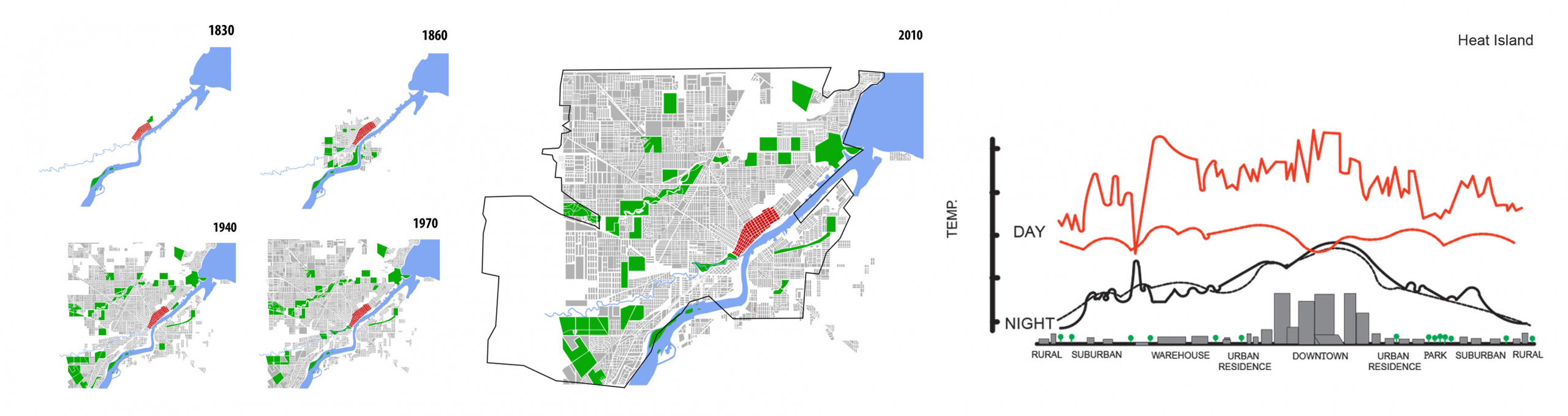

Acclimatizing to Heat in a Legacy City: Urban Heat Islands, Segregation and Social Connections in Toledo, Ohio

Yong Huang & Andreas Luescher, Bowling Green State University

Sujata Shetty, University of Toledo

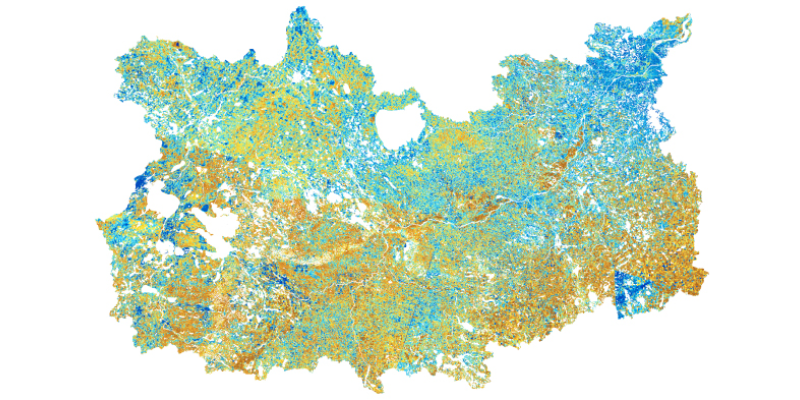

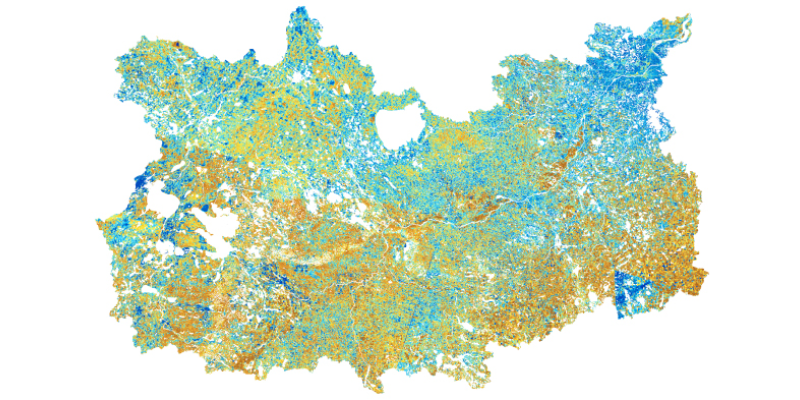

(Image: Toledo Green Spaces and Heat Island Analysis)

Climate change in Toledo, Ohio once a thriving part of the constellation of cities supporting Detroit’s auto industry, is already noticeable through an increase in average air temperatures, with predictions that they will continue rising (City of Toledo, 2021). Region-wide, climate change is projected to increase the risk, intensity and duration of temperature extremes and that has certainly been true in the city as well (GCA, 2020). One major contributor to these prolonged high temperatures are Urban Heat Islands (UHIs), urban areas that are significantly warmer than their surroundings chiefly because of concentrated heat emitted from the built environment, vehicles, and industrial land uses. As in other old industrial cities, Toledo’s urban areas suffering from the heat island effect are expected to be most affected by heatwaves, putting the city’s low-income and elderly residents most at risk.

The proposed interdisciplinary seminar and studio will focus on the intersection between heat events and the structure of the City of Toledo, socio-economic and physical. The main question we ask is: how can heat mitigation architecture and planning interventions further social equity? Our aim is to examine the connection of nature to human experience, and to integrate the wellbeing of individuals with the design of healthy public spaces and neighborhood-wide environments. The joint venture will advance and bolster climate literacy in Northwest Ohio.

References: City of Toledo (2021) Climate change Vulnerability Assessment for Stormwater

GCA (2020) Global Center on Adaptation: Temperatures in the Great Lakes are rising and putting the vulnerable at risk

HONORABLE MENTIONS

Tourism as Environmental Disaster: Vulnerable Landscapes and Vulnerable Populations on the Atlantic Coast Barrier Islands

David Franco, Ulrike Heine, Andreea Mihalache and George Schafer, Clemson University

(Image: Tourism as Environment)

Barrier islands are vulnerable landforms critical for the protection of coastal ecosystems and communities, whose rich vegetation merges with water in marshlands and beaches. During the Jim Crow era, they were the safe havens of self-sustaining Gullah-Geechee communities from the Carolinas to South Florida, until when a massive invasion of vacation homes, hotels, and oversized tourist infrastructure began to displace them during the 1950s. Bringing together design, theory, and technology, this course addresses the abusive tourist practices that have shaped the Atlantic coast as we know it, through alternative approaches to tackle these landscapes’ social, environmental, and spatial challenges.

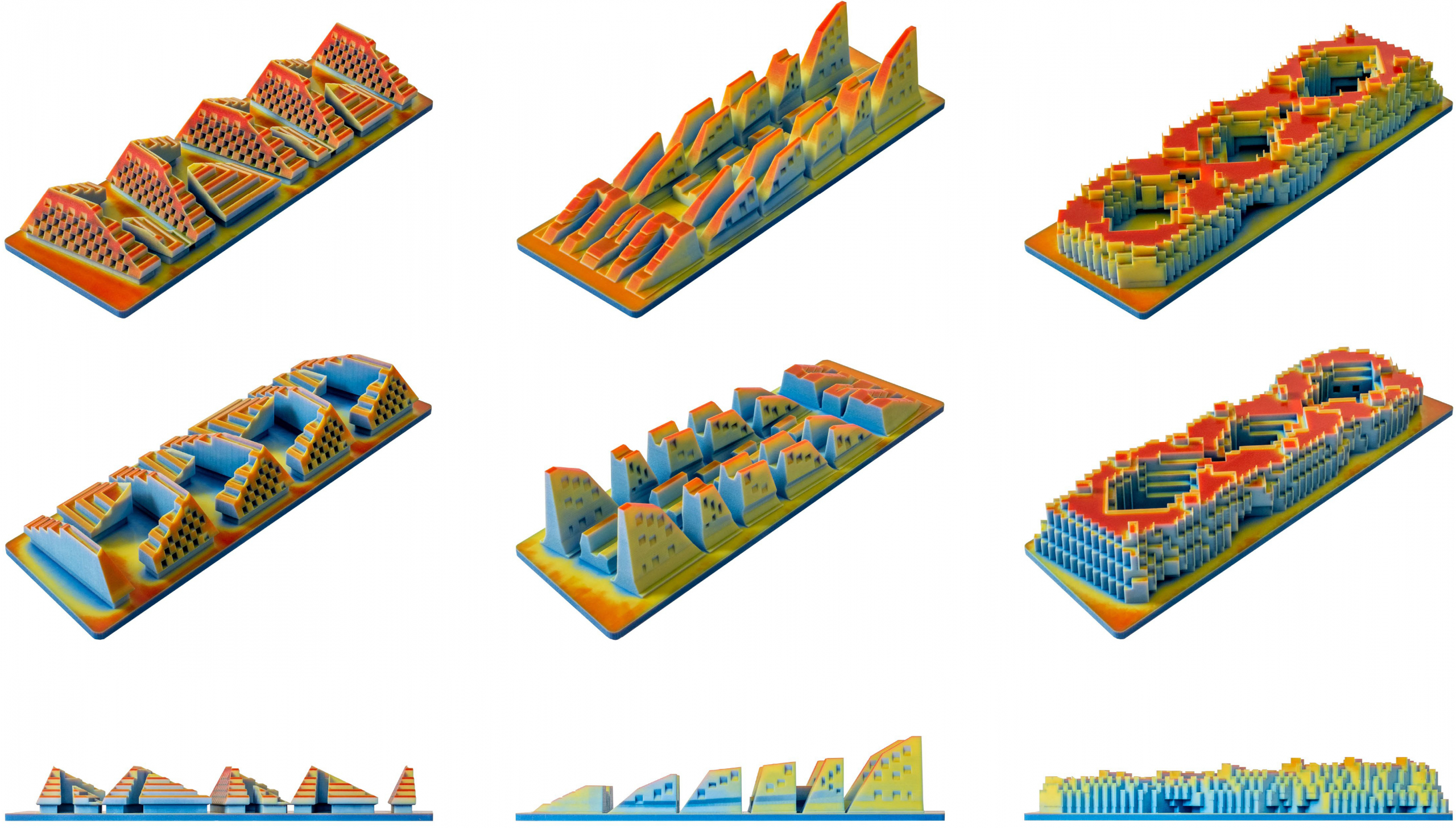

Energy Collectives: Towards a Self-Sustaining Neighborhood

Lawrence Blough, Pratt Institute

Simone Giostra, Politecnico di Milano

(Image: City block housing proposals mapping yearly solar radiation – IDC funded studios. Blough & Giostra, 2019-21)

Our proposal calls for radical new models of inhabitation, production, and protection of vital ecosystems by pairing objective environmental analysis with speculative architectural scenarios. A model for a self-sufficient settlement located on the city’s periphery will integrate overlapping scales of production and conservation. Animated by new modes of co-living, working and shared resources, it will provide a roadmap for future growth of the city and its environs. Energy performance in buildings is form dependent—addressing resource scarcity and environmental degradation demands a new design aesthetic and formal approach based on ecological inputs and necessity. The four vital infrastructures of Food, Energy, Water and Waste (FEW2) will be investigated for their design agency through a paired research seminar and design studio in order to effectively tackle the climate and energy crisis.

2021 WINNERS

Gulf: Architecture, Ecology, and Precarity on the Gulf Coast

Matthew Johnson & Michael Kubo, University of Houston

Much of contemporary carbon culture and its environmental consequences can be traced back, forensically or circumstantially, to the U.S. Gulf Coast. The extraction of fossil fuels has made the Texas-Louisiana coastline a global center of oil production, sprawling along the bayous and wetlands of Beaumont, Galveston, Baton Rouge, Lake Charles, and Houston.

While the products of carbon have fueled the mega-region’s expansion, the sprawling oil industry has produced structural inequities in its built environment. Racially segregated “fenceline” communities sit in uneasy proximity to petrochemical plants, subject to the environmental impacts of polluted soil, air, groundwater, and aquifers. Toxic clouds, spills, and other disasters are common in these areas, particularly during extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change. In this context, an examination of the relationship between architecture, urbanism, climate, and environmental justice is urgently needed.

The proposed “superstudio” (a combined research studio and seminar) deals with the history and speculative futures of petro-culture’s long century and its aftermath. We will engage the wicked problems facing individual communities along the Texas-Louisiana coast, from flooding and pollution to toxic development patterns, and propose methods for repairing the discriminatory effects of petro-culture on the broader environment of the Gulf.

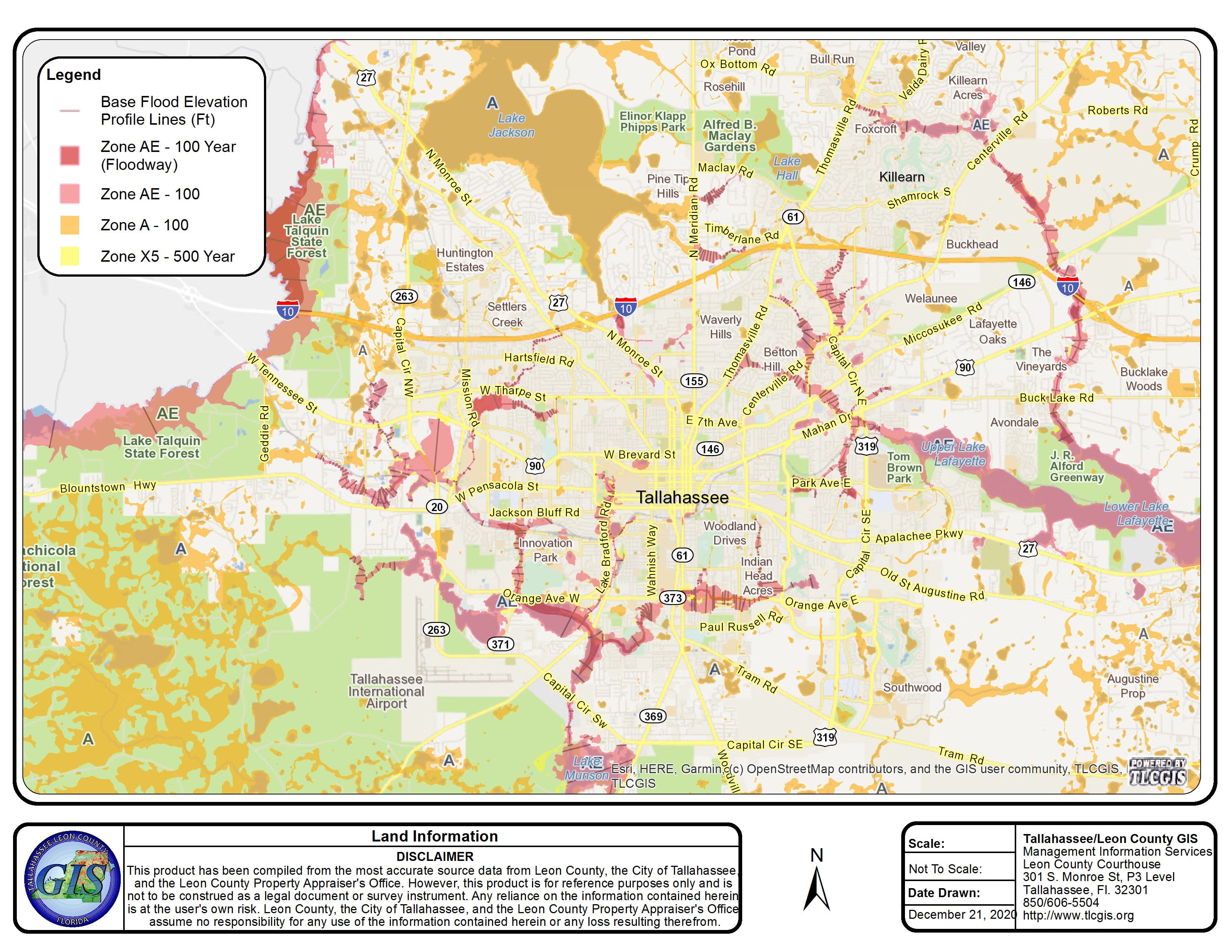

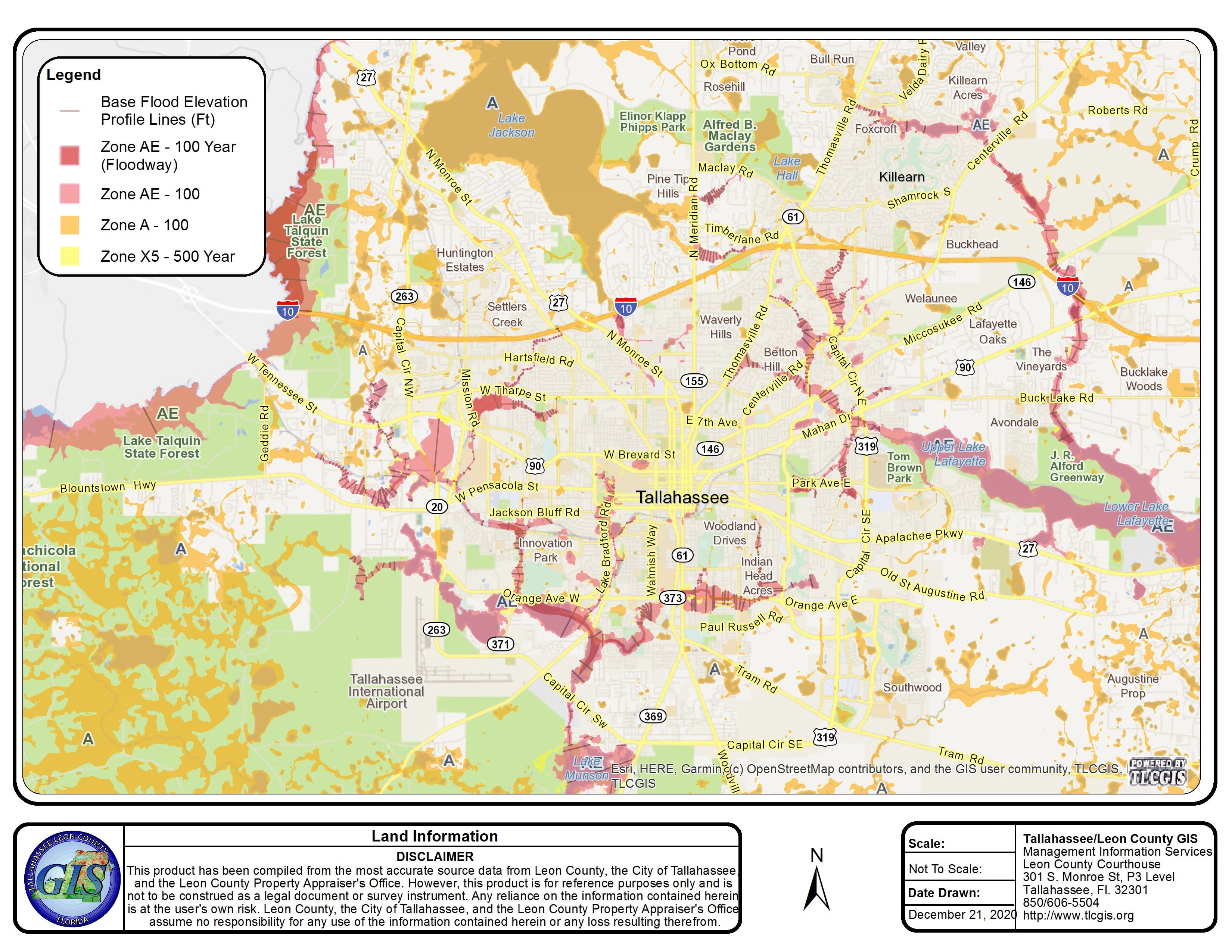

Hazard Mitigation + Race + Architecture

Mahsan Mohsenin, Reginald Ellis & Andrew Chin, Florida A&M University

“Hazard Mitigation + Race + Architecture” is a cross-disciplinary collaboration that brings together faculty from two departments at the Florida A&M University: architecture and African-American history. The goal is to provide a cross-disciplinary approach to climate change and recognize Florida’s challenges as ethical and political issues, rather than purely environmental or physical in nature. Every year, Florida is one of the states that is most impacted by climate change through flooding, hurricanes, etc. According to a 2016 US Environmental Protection Agency report, the Florida peninsula has warmed more than one degree during the last century. The sea is rising about one inch every decade and heavy rainstorms are becoming more severe. This is of special concern to minority and underserved communities; specifically, African-Americans, who are often impacted the most by climate change. But as architecture students learn about sustainability, the intersection of race and architecture adaptations are not widely discussed. Architectural responses to climate change include floating or amphibious structures, design for lateral forces, and merging hazard mitigation with architectural design. The goal of this course is to introduce segregation and planning inequities in the discussions of architectural responses to hazard mitigations.

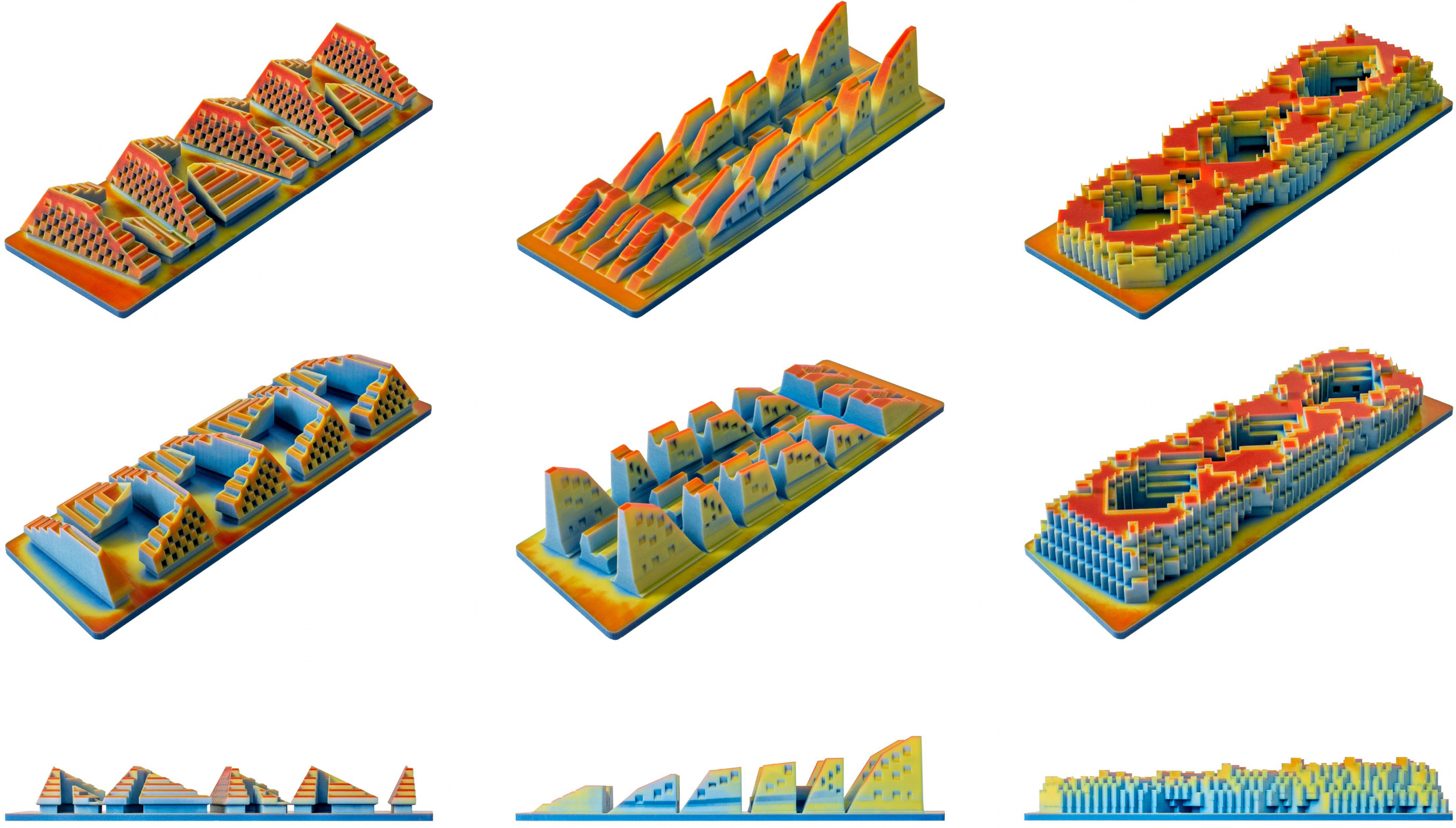

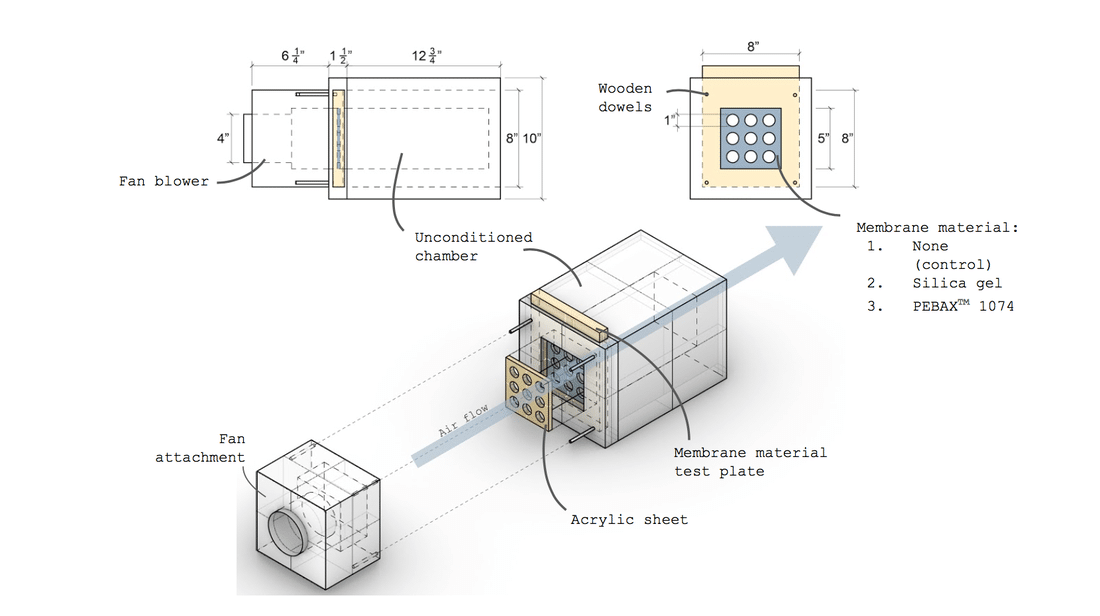

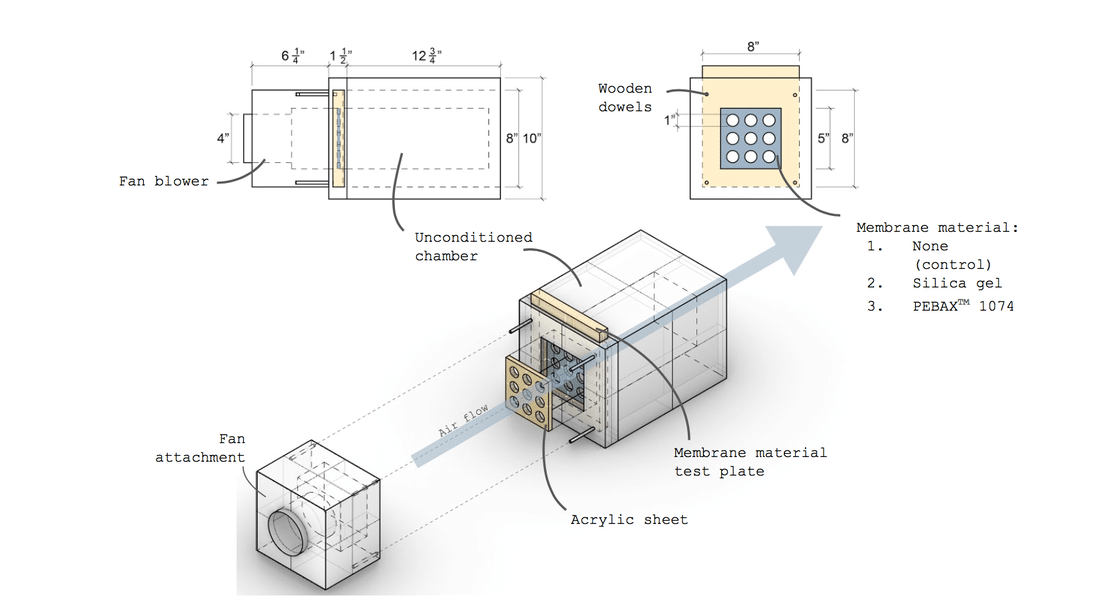

High-Performance, Low-Tech

Liz McCormick, University of North Carolina at Charlotte

(Ana Sandoval and Michelle Barrett)

The global increase of atmospheric temperature rise, combined with the rapid growth of previously underdeveloped climate zones, presents a growing need for low-cost solutions that serve those without access to advanced technologies. Within the architecture, engineering, and construction industry, high-performance buildings are often associated with expensive, high-tech strategies that rely heavily on complex mechanical systems. New technologies may change the way that one designs, but they cannot replace the basic climate-specific principles celebrated by vernacular architecture. In response, students will explore the vernacular strategies associated with rapidly urbanizing regions in order to translate their character, physical qualities, and thermal capabilities to a commercial scale, reducing the reliance on energy-intensive mechanical systems while developing a new, climate and culture-specific urban identity.

This course mixes historical referencing with physical experimentation to demonstrate performance metrics and explore the ways building systems could engage and empower the occupant. Integrated as dynamic systems, buildings could better react to fluctuating environmental conditions. By combining students from across the campus, this interdisciplinary course strives to bridge the gap between design, performance, and building analytics. In the spirit of affordable, low-tech and climate-specific enclosure systems, this class will employ accessible physical testing methods to make building technology innovation more accessible.

Just Play

Karla Sierralta, Cathi Ho Schar, Prisma Das & Phoebe White, University of Hawaii at Manoa

“Just Play” is a set of coordinated courses in architecture, landscape architecture, and urban and regional planning at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa that will focus on climate change and design justice. The objective is to explore learning through teaching, and teaching through play. Students will conduct research and design place-based, equity-focused educational games for a five-week course, which will be offered to 12 participating high schools through the Mānoa Academy program, led by the College of Social Sciences. University students will work in partnership with the Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability, and Resiliency (OCCSR), to build on their 2020-21 Climate Change Open Houses and talk stories. These open houses gather information that will enable the OCCSR to develop equity initiatives for Honolulu’s Climate Adaptation Strategy. Students will integrate the OCCSR’s community input with research to design interactive games that cultivate citizenship skills such as empathy, negotiation, decision-making, and collective action to foster resilient island communities. “Just Play” seeks to engage climate change from an equity standpoint, focusing on social action, empowerment, scenario-planning, systems-understanding, design, and education, reaching beyond technological solutions. It represents a multi-departmental effort to expand our reach as educators and advocates.

Professional Practice 3: Future Practice

Megan Groth, Woodbury University

(Ymzp85)

The direct relationship of the global climate crisis to the built environment—the realm of the architect—means that architects are uniquely positioned to respond to the climate emergency in and through their work. Unfortunately, the architect’s lack of agency, in part due to the traditional architecture business model, the profession’s codes of conduct, value system, and lack of ethical framework, does not make it possible for architects to act to the degree and with the speed that is required. “Future Practice” asks students to situate architecture practice in the larger context of our communities, cities, countries, and planet and ask: How do we value what we do as architects? What do we need to achieve in practice in order to pursue climate justice? How then do we create new, implementable value systems by which to restructure our work in order to align it with those goals? Using readings from a variety of different cross-disciplinary sources and thinkers, students will be encouraged to think beyond what practice is and into the radical realms of what practice could become in the future.

HONORABLE MENTIONS

Living by Water

Amee Carmines & Carmina Sanchez-del-Valle, Hampton University

English Literature and Community Design Issues Joint Micro Seminars on Place and Community

The joint micro-seminars in “Living by Water” focus on the interaction between place and community, particularly at times of crisis. Architecture students in a course on community design collaborate with students in a course on the novel to visualize literary works to create an environment that promotes a critical dialogue, crossing invisible and implied disciplinary boundaries. In the texts, the landscape of communities built and destroyed around constructions of racial hierarchy link to the construction of the narrative. This collaborative inquiry reveals the structures, physical and social limitations, and strategies needed to shelter human beings in ways that enrich cultural expression; and shows how knowledgeable and skilled local communities are about their built environment.

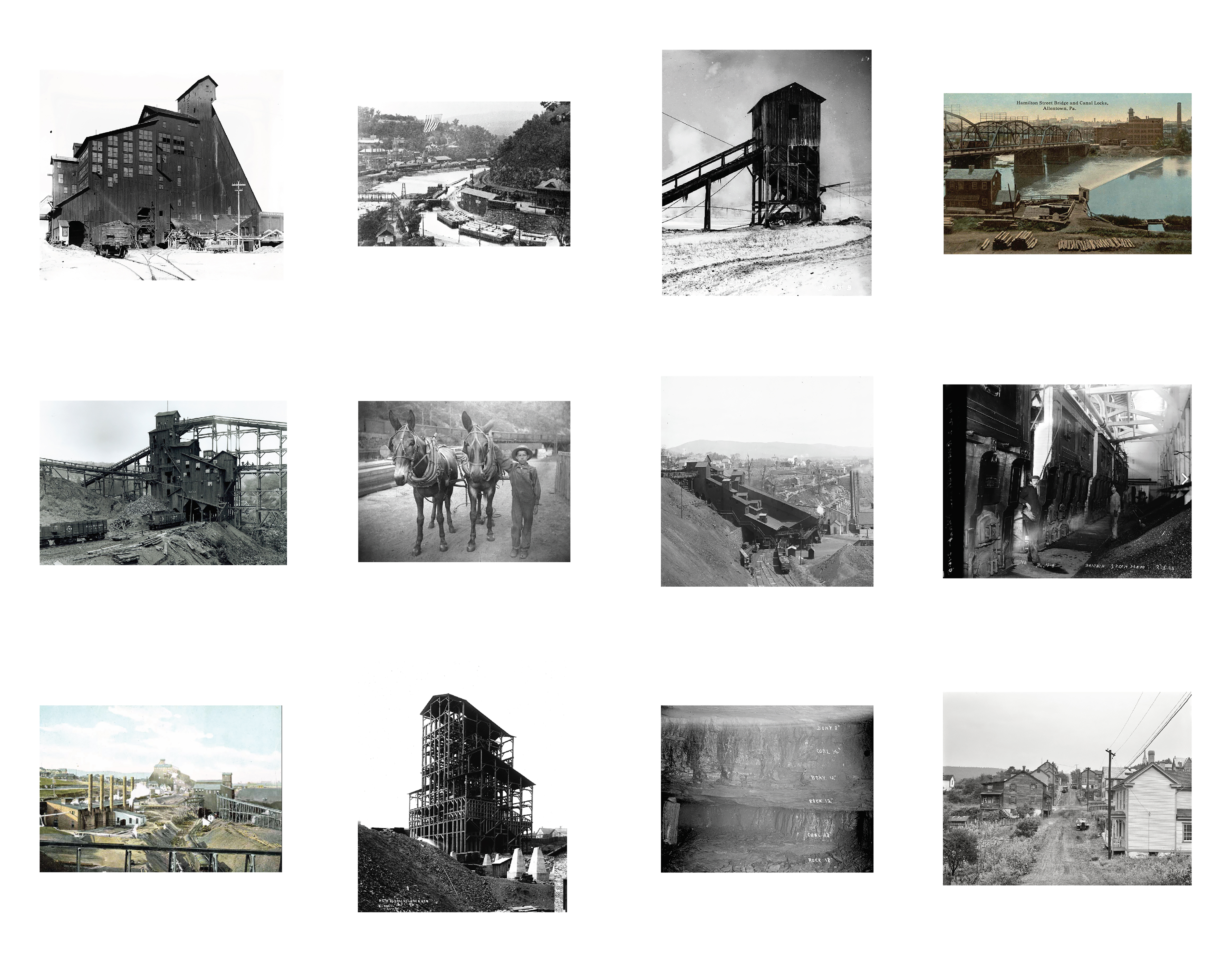

Spaces of Coal

Pep Avilés, Penn State University

Space of Coal + Anthracite Culture

The industrialization of modern states following the Enlightenment ran parallel to the increasing extraction and production of soft coal and anthracite. Coal became the leading source of energy during the nineteenth century as a replacement both for other combustibles (wood) and power sources (water and wind) and contributed in turn to the rapid development of transportation, industry, and—eventually—the modern urban experience. Coal-based capitalism was a global environmental project from the very beginning, affecting the morphology of modern cities as a consequence of iron and steel construction and of the alteration of natural landscapes to accommodate the new infrastructures that industries demanded. Regrettably, economic development triggered climate change and global warming. Although the heyday of coal production in the US occurred around the beginning of the twentieth century—consumption declined steadily following World War II, once oil proved to be a more effective and profitable source of energy—the global impact of past coal mining on the environment has not been reversed: currently, coal still remains at the origin of the majority of global CO2 emissions in the atmosphere, contributing dramatically to global warming.

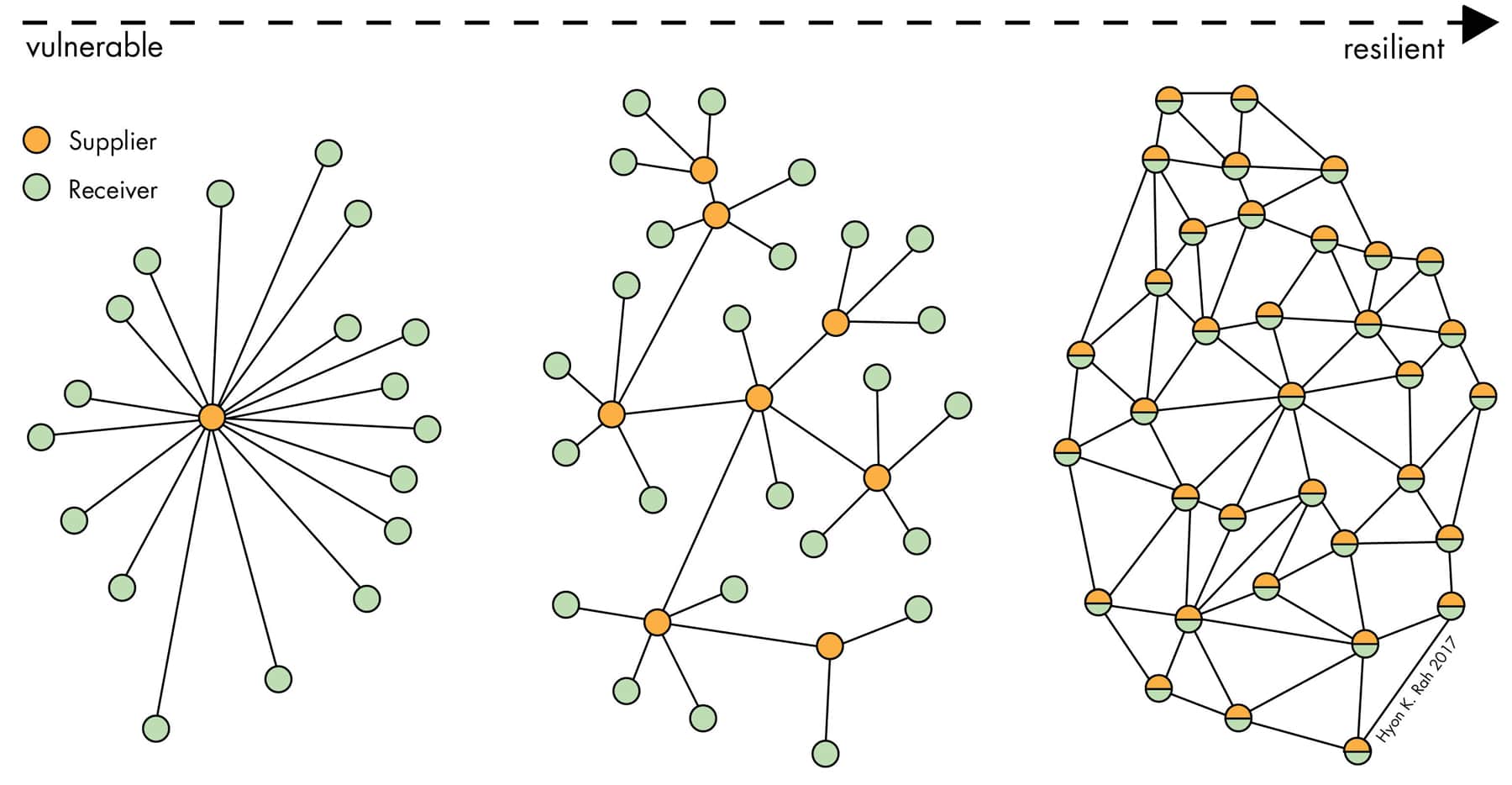

The Built Environment

Hyon K. Rah, University of the District of Columbia

Climate change, increasingly frequent and devastating disasters, and the built environment are inextricably linked. This calls for a fundamental shift in how we design, plan, and manage the built environment – from self-referential and siloed to more contextualized and systems-based. This introductory course, required for all undergraduate architecture majors and cross-listed within the College of Agriculture, Urban Sustainability & Environmental Sciences, takes a holistic look at different scales and disciplines contributing to the built environment along with the social, economic, and environmental interdependencies and influences. Various design, technical, financial, and policy tools and strategies are explored. The goal is to better prepare our students for increasingly complex and challenging conditions and the role of interdisciplinary facilitator architects are required to play.

2020 WINNERS

Adaptation to Sea Level Rise

Mason Andrews, Hampton University

A two semester cross-disciplinary course focusing on adapting to the impacts of sea level rise in existing urban neighborhoods in sadly soggy southeastern Virginia has been in place since 2014. In the first semester, students of architecture, engineering, and, intermittently, of pure and social sciences, hear lectures from subject matter experts on soils and hydrology, preservation, urban design, public policy, social justice, and more. Simultaneously, community engagement with stakeholders begins, as does a series of design initiatives in which the architecture students and faculty model the processes of studio-based learning. The latter is the subject of a current NSF program study by ethnographers. While student work has been the basis for a $115,000,000 HUD NDRC implementation grant, it is also true that, as in efforts outside academia, disciplinary silos keep professions ill-equipped to work successfully together. In a subject as vast as the planning of adaptation strategies, however, the only path forward is bringing the expertise of a wide array of knowledge types together; there is inadequate time for sequential disciplinary speculation. Next year area professionals will join the design studio as well. It is hoped a new community of practice will emerge modeling effective transdisciplinarity.

Public Issues, Climate Justice, and Architecture

Bradford Grant, Howard University