Infrastructure in

America

For the Green New Deal

The writers of H. Res. 109 are to be congratulated. It’s notable that in this resolution, the most prominent collection of ideas and proposals that has come to be known as the Green New Deal (GND), they have decided to make human justice and equity major parts of the climate change mitigation project. In both sections of the proposal—the six pages of “whereas” and the eight pages of “resolved”—the seemingly permanent systemic injustice of American society, and the increasing inequality of the last few decades, are acknowledged and also tightly bound to both the explanation of the climate problem and the prescriptions for solutions. This is a strategic decision on the part of the framers of the Green New Deal, and it’s useful to consider why they made that decision. I think it’s possibly because alternative scenarios for addressing climate change can be imagined, so the framers of the GND are insisting from the start on the plan that is the most just.

This process of scenario building is basically a science fictional exercise, imagining various possible futures starting from the current moment, and then arguing for one over the other. In this case, it might seem reasonable to consider climate change to be a technological problem only, of fossil fuel burn and thus the necessary decarbonization of energy generation, also of transport, agriculture, industry, and construction. This decarbonization could possibly be enacted by the imposition of a command state careless of people’s lives, perhaps like the authoritarian governments of World War Two. It’s thus possible to imagine a ‘successful’ but nevertheless dystopian response to climate change, in which democracy and people more generally are not trusted to be adequate to the emergency, and authoritarian or totalitarian governments must then attack the problem of technology transfer using ordinary people as shock troops to be sacrificed for a higher cause. The imagination here is perhaps seeing images of Stalin’s use of the Soviet people in the war against Germany, if not Orwell’s Big Brother himself.

Against this bad scenario, the writers of H. Res. 109 have taken great pains to emphasize that any truly successful coping with the climate emergency will have to regard everyone involved as equally important. It acknowledges that the poorest among us, who have consumed the least and burned the least carbon, are still the first to suffer the consequences; and it promises to enact policies that rectify that situation, making a more just and equal society by way of the very same efforts initiated by the federal government to deal with the changing climate. Many people hired to do good work through just practices is seen as the solution to the problem.

I think this is right. It is not only more realistic than the police state approach, it is really the only way success can be achieved in this struggle. The GND benchmark of success has been set at prosperity for all not just because this is morally right, but because it’s the fastest deployment of the main available resource, which is people. That a people-friendly approach is the most likely to garner widespread popular support is not the least of the virtues of this approach, because it will need citizen and voter support to be enacted. It’s an approach that is made implicitly in the pages of H. Res. 109, without an explicit justification for it as the best way, and so that justification needs to be made and defended outside those pages. We need to clarify that the climate project is so all-encompassing that it requires a huge highly-skilled workforce, and that universal higher education and full employment are therefore necessities for its success.

Because the New Deal of the 1930s is very clearly invoked by the name “Green New Deal,” we should look to the original to see if we can learn useful lessons from it. One important thing to recall is a negative lesson, and H. Res. 109 seems very sensitive to this; the original New Deal encoded discrimination, and the Green New Deal is explicit and meticulous about being inclusive.

Another important thing to recall is that the New Deal was not a single action called out in advance, but an improvisation that lasted many years. There were at least five distinct moments comprising what now gets called the New Deal: the Hundred Days in 1933, Social Security in 1935, the Keynesian stimulus of 1937, the war spending that began in 1942, and finally the GI Bill of 1945, which was FDR’s own idea, and his final contribution to the process. The New Deal therefore unfolded over thirteen years that included all kinds of unpredictable developments, including the largest war in history. No one in 1932 could have outlined the New Deal in advance. It was not just a program, but the name for an era.

Remembering this, it becomes obvious that it’s pointless to criticize H. Res. 109, or the even the idea of a Green New Deal, as if they were a full blueprint for the next three decades. That kind of blueprint is not possible, so no plan could meet that standard. Attacking the GND on that basis is a straw man argument, the straw man being the idea that any one plan could solve all the problems we’ll face in the next decade. The GND simply proposes an overarching vision of political action, with specifics listed to start a long process of transformation. Judged as such, it’s good.

Of course it’s nevertheless getting attacked from both sides. On the one hand it’s accused of being impossibly utopian and totalizing, thus incapable of being enacted in legislation, or if it were enacted, too planned and heavy-handed; on the other hand it’s accused of not going anywhere near far enough to get the job done, and that if the writers of the resolution were serious they would have included even more radical proposals. This double attack is one feature of the straw man argument, and maybe also an indication that it has hit a line that can shoot the gap of possibility.

But when the criticisms are from allies of the cause, meaning those who agree we have to take serious action as a society, one must keep in mind what Freud called “the narcissism of small differences.” With this phrase he was pointing out those moments when we care more about winning arguments than about getting results. We’ve all seen the phenomenon, and we’ve all indulged in it ourselves. Very often our allies are the only people who will listen to us and understand our terms and our frame of reference. Ultimately they’re the only ones available to argue with, so we do it with gusto, when really what we want is to win arguments with people who are not listening and will never agree with us. Quite often the result of this infighting is a failure to enact changes that a majority of people actually want. A minority not listening thus wins the day, holds on to power, and uses it in ways disastrous for all—including the minority itself.

So a commitment to solidarity is important. H. Res 109 is explicitly inclusive precisely to encourage that sense of solidarity. And it’s important to remember the front is broad. Lots needs to happen, and different people will naturally take an interest in different parts of the process. The basic fact is we need to start now to deal with climate change, by taking some actions. Other actions will follow that start. An overarching vision is good to have for basic orientation, and that’s what H. Res. 109 tries to provide. But we should also remember that even quite different overarching visions will often still coalesce toward an agreement that similar actions are needed to enact these visions, especially at the start. So everything should be judged in a spirit of solidarity. We’re on the edge of causing a mass extinction event that will hammer humanity too, so what we need are results, and quickly. Getting that comes down to being roughly united with people you don’t fully agree with.

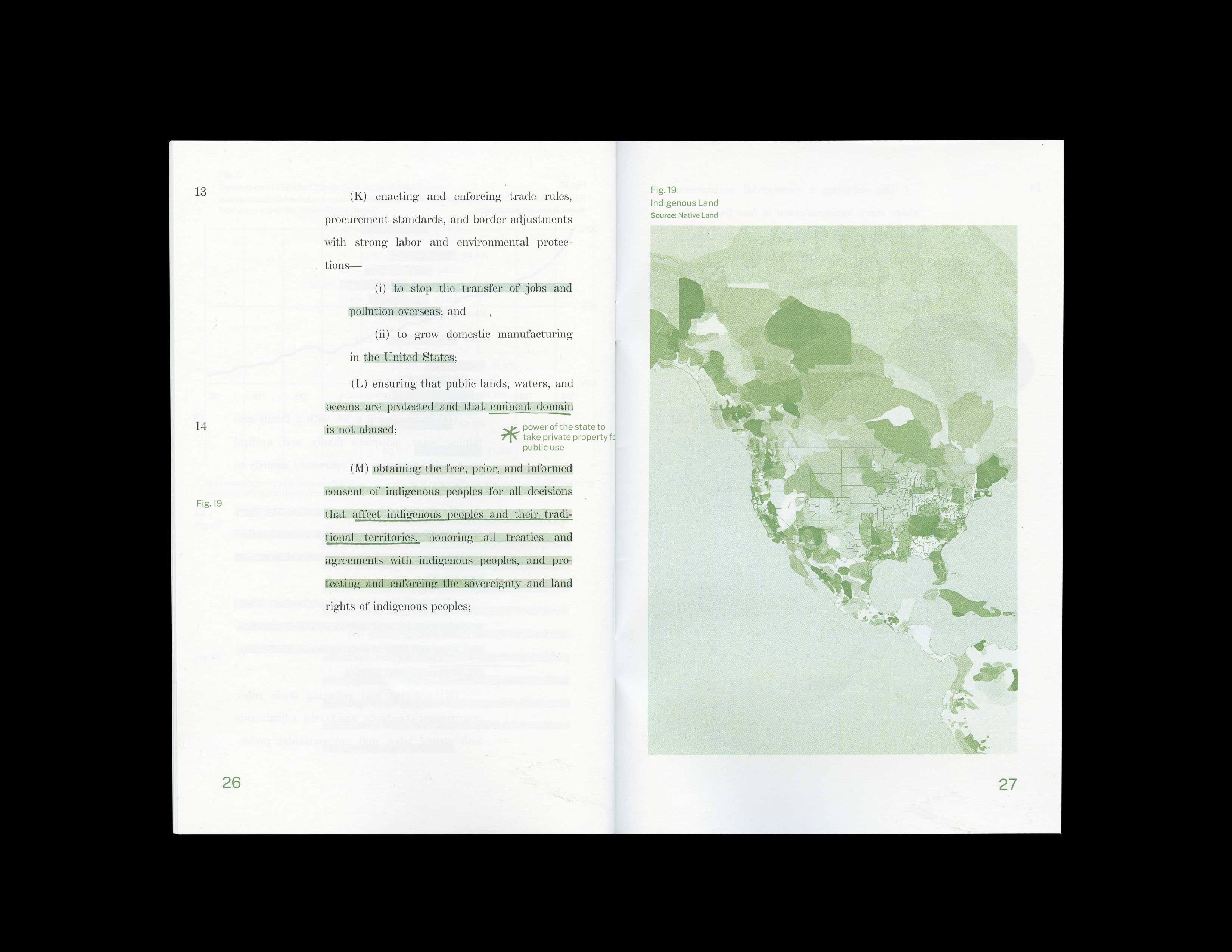

H. Res. 109 only refers obliquely to the matter of how all its good projects will get paid for, and in the discussions of it, the suggestion has been made that it can be paid for by a more progressive tax rate. I think a steeply progressive tax rate is a good idea for many reasons, but it should also be pointed out that both the New Deal and the Green New Deal are expressions of a Keynesian view of the government/business dynamic, in which stimulus deficit spending is seen as good when necessary.

Inherent in Keynesian economics is an acknowledgment of the power of the state by way of seigniorage, meaning the ability to create money from scratch. This fiat money is the only money people really trust, and that means, as Keynes pointed out, that states are not in the same position as individuals or corporations when it comes to debt. States can make new money, spend it in targeted ways (in the post-2008 quantitative easing the new money was unfortunately simply given to private banks to loan out however they liked), and then rebalance the books later by way of increased tax revenue, or simply the creation of yet more money. As long as people continue to trust money itself, there is no downside to this money creation. The quantitative easing of the post-2008 crash, which despite its flaws perhaps prevented a recession from becoming a depression, proves the point that quite a lot of new money (about 15 trillion dollars during the post-2008 quantitative easing) could be injected into the world without destroying trust in money.

That’s another underlying assumption of H. Res. 109: as was true during the New Deal era, deficit spending by the federal government—in essence the creation of new money—can stimulate the general economy in good ways. The resolution is implicitly calling for what is being labeled a “carbon quantitative easing.”

I think it would be a good thing, in the discussion of the GND, to point this out explicitly. That would make it clear that it’s advocating a return to Keynesian economics, in reaction against the neoliberal, free market, anti-government economics espoused by Milton Friedman and others, and enacted by governments worldwide ever since Reagan and Thatcher, with disastrous consequences for both people and the planet. The neoliberal turn has seen rising inequality and rising environmental destruction, all for the sake of private profit. Governments have been dismantled as much as possible, thus making more room for private enterprise acting in Ponzi scheme fashion, getting rich while leaving the unpayable true costs on the shoulders of future generations. That’s the story of the last forty years, and now as we attempt to deal with the immense crisis of climate change, that has to change. The tide has to turn back toward governments as positive and desirable economic actors. They are the people’s company.

So it has to be made clear that in this decade of crisis, and maybe always, governments are not the problem, they are the solution. This reversal of Reagan’s ridiculous saying must be insisted on for the Green New Deal to work, both theoretically and practically. Governments are the only organizations with the power to cope successfully with climate change, precisely because they make money in the first place and can therefore direct where money gets spent first. This is crucial, because saving the world doesn’t yield the highest rate of return, indeed it might not even be profitable; so the market will not do it.

H. Res. 109 implies this Keynesian belief without saying it explicitly. The resolution is very careful to call out limits to eminent domain, and support for and nurturing of small businesses and family farms, precisely to dodge any accusations of advocating all government all the time. It is, in effect, calling for Keynesian capitalism rather than free market capitalism. It is calling for the New Deal Democratic party to prevail over the neoliberal Republican party, while staying entirely within the American “window of acceptable discourse,” which is to say America’s historical reality so far. Whether that will be enough remains to be seen, but it’s undeniably the only plausible way to get started given the world we have right now. It seems to me the writers of H. Res. 109 decided not to discuss economic theory, nor even funding, along with many other thorny issues, except in the most indirect ways, specifically to add clarity to their version of a start. That leaves it to we the supporters of the Green New Deal to debate and elaborate on the theories supporting the proposal.

In so doing, support for Green New Deal is also a great opportunity to reaffirm American democracy. “That government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from this Earth.” Note the “shall not” in that phrase: this is an injunction, a call to be “dedicated to the great task remaining before us”; it’s said in the imperative mood, which contains within it the future tense. It is, in short, another science fiction story. It’s one of the most powerful and inspiring (and compact) science fiction stories ever penned, an awesome utopian statement by that great American science fiction writer, Abraham Lincoln. Forged in the crucible of our great civil war, a war which ended slavery in America and made one big painful step in the long road toward justice, it is still a story that most Americans would agree to and support. Government of the people, by the people, and for the people: this phrase should replace the single word government every time we use it, to remind us what government in the United States is supposed to be. This is particularly true when arguing for the Green New Deal.

So: first a working majority of Americans needs to believe in some version of the Green New Deal as the best response to the crisis. This is a matter of education, rhetoric, persuasion, and sheer persistence.

Then this working majority’s votes need to elect representatives who will legislate the start of a Green New Deal.

Then it will be necessary to insist that our elected representatives actually do what we elected them to do. These wishes shouldn’t be subverted by a rich petro-oligarchy that spends its wealth to buy media, political representatives, and ultimately legislation. Achieving this might take some reiteration and some replacement of representatives, but elections come frequently. Eventually good results will follow.

All this necessary work will be a test and demonstration of democracy in action. It will be a test of the stories we tell each other, of how persuasive they are. The Green New Deal is a good first step in what FDR called “bold and persistent experimentation.” That’s what we need now. So let’s hail and support the Green New Deal as the best expression yet of that good start, and get to work from there.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.

"The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations" was produced by the Buell Center on the occasion of "The Green New Deal: A Public Assembly," held at the Queens Museum on November 17, 2019.